Jonathan Rosen and his best friend Michael Laudor grew up in bookish households in New Rochelle, N.Y. in the 1970s. They were expected to do meaningful intellectual work, and for a while, Rosen writes in The Best Minds: A Story of Friendship, Madness, and the Tragedy of Good Intentions, things went as planned. Both went to Yale. After college, Rosen worked in journalism—he’s since authored several books—and Laudor got a lucrative job in management consulting, even as he struggled with his mental health. In his 20s, Laudor was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Though he would spend months in a psychiatric hospital, Laudor graduated from Yale Law School—an achievement heralded in a New York Times feature piece that described him as a “genius.” Before long, Laudor had more than $2 million in book and movie deals for the rights to tell his life story.

But delusions had long stalked Laudor—he sometimes believed his parents had been replaced by imposters, and frequently woke in terror believing his bedroom was on fire—eventually overwhelmed him. In June 1998, the 35-year-old Laudor killed Caroline Costello, his pregnant fiancée, at their home in Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y. He stabbed her to death, Laudor told police, because he worried that Costello would have him admitted to a hospital. The story led the front page of New York City tabloids for several days. Laudor has been in a psychiatric hospital since the crime.

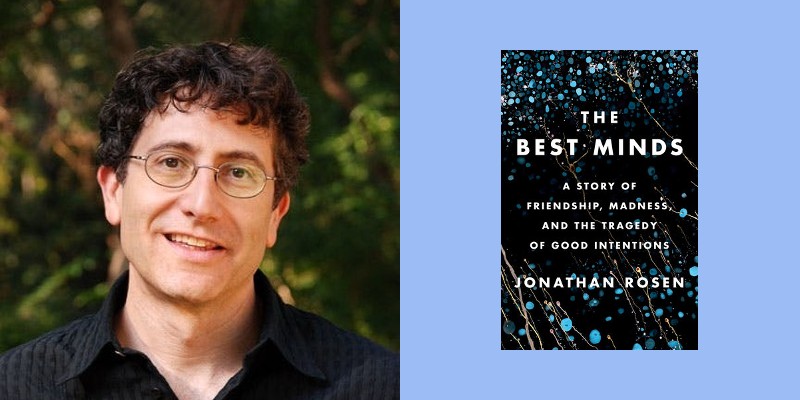

Rosen’s book is intelligent, absorbing and heartbreaking, an intensely personal story about, among other subjects, the misjudgments that plagued American mental health care in the last decades of the 20th century. He talked about his book in a recent video interview.

Kevin Canfield: This was clearly a painful story for you to tell. Why tell it now?

Jonathan Rosen: It’s a hard question to answer, because it isn’t as if I suddenly thought: now I’m telling the story. I didn’t even really know what the story was—I knew that my childhood friend had killed somebody, and I knew that when it happened, I didn’t want to write about it, which I was asked to do by people who knew that I knew him when he was in all the newspapers (after Laudor’s arrest). It was this dreadful thing that I was evading, and it was suddenly just a kind of encounter that I felt I needed to have as a writer.

KC: It’s a rich, fascinating book long before we get to the crime. You write in particular detail about the intellectual curiosity and debate that was encouraged in your home and in Michael’s. What was it like to revisit your youth in such an intense and specific way?

JR: I found myself recalling things that I hadn’t thought about in years—and hadn’t wanted to think about. I knew that the story was going to bring me in touch with severe mental illness. And I did not want to encounter my childhood, which felt somehow equally daunting. I wouldn’t have written the story if it hadn’t been a very public story, if all the lurid details hadn’t been on the cover of the (New York) Post. But I also wouldn’t have written it if I hadn’t felt it was partly my story.

Once I realized that I would have to imagine my way back into my childhood, in a sense everything followed from that. It was imagining a time before all these things were inevitable.

KC: You and Michael were raised to believe, as you put it in the book, that “intelligence bestowed a kind of blessing,” that it might inoculate you against tragedy.

JR: The idea that being smart was a way of rising above ordinary life was just present. My mother was a writer, and so the idea that if you told the story, you were the master of the story—you weren’t at the mercy of it. My dad was a professor of literature. I wouldn’t go so far as to say they disdained ordinary existence, but there was a way in which—and this is a shameful thing to have encountered, to have to acknowledge—ordinary existence was what you hoped to avoid. Thinking was your job, and Michael’s brain worked better than mine. He always seemed like a touchstone of high mental functioning. He read really fast, he had a photographic memory.

KC: A big part of the book is how mental illness was thought of by the public and treated by the medical community in the second half of the 20th century. For a time, you write, films like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and a few postmodern academics made mental illness seem like a charming quirk, a sensible response to an insane world. Did this have an impact on Michael’s trajectory?

JR: Take a touchstone movie like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which is based on a book by Ken Kesey, who, as part of a drug-testing program at the Menlo Park VA hospital, was getting LSD tested on him. That was part of MK Ultra (the infamous CIA program). He liked it so much that he got a night job as a janitor at the hospital. He would be tripping and walking around cleaning the halls, and his encounters with psychiatric patients was entirely through the scrim of a hallucinatory world.

In the movie at least, McMurphy (played by Jack Nicholson) doesn’t have a mental illness. He’s like a Kafka character—he woke up one day and he was in a psychiatric hospital. Michael would sometimes refer to himself, when he was in the halfway house (in his 20s, after his first stay in a psychiatric hospital but before the murder), as the McMurphy character. What it really meant was: I’m here through some error and I can’t get out. Everybody took it for granted therefore that you wound up inside for almost arbitrary reasons.

And so the absurdity of life, the unfairness of structures and society and institutions, was all present for us. What’s really amazing is that when you read about how certain laws were passed—commitment laws, let’s say (these governed who could be legally compelled to enter a psychiatric hospital)—people would wave copies of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in the air. So a novel that grew out of a drug experiment informed laws that in turn shaped the culture.

KC: When Michael signed his book deal, was there a hope that he could write his way out of his problems?

JR: I think that was the notion. First of all, he was bringing the news from a place where most people didn’t come back to tell the tale. So that was exciting for everyone. And this conformed to what our idea of being a writer was. That you’re thwarted by life and that the experience of being wounded or broken becomes the very thing that fuels the story that you tell, which becomes the evidence of your ultimate triumph. It was the idea that you tell your story and therefore you are the victor. The whole premise was that he’d defeated something and therefore was now going to tell the tale.

KC: Can you tell me about the nuts and bolts of putting the book together? You had journals that you’d kept since you were a teenager, you did a lot of interviews.

JR: I interviewed a ton of people. At the beginning, it felt mysterious: Oh, I think I’ll call the Hastings police officer whose name I saw in People magazine. He had already retired, but I found him and he had a packet of clippings. The case had haunted him, and he was so eager to talk about it. One thing led to another. I would be talking to a middle-aged woman who was a girl I once had a crush on. Everybody remembered the story and carried it around with them.

And many people also imagined that I would tell it. It wasn’t as if, Oh, we’ve been waiting for you, but there was a sense, because they associated us as kids together, that it had also happened to me.