Not long ago I was contacted by a businessman named John Kleinheinz. He’d read my novels, and he had a story he wanted to tell me about his life. It was a little time-sensitive, he said, because he’d just become the last living person who knew this particular story. His former business partner has just been killed in a helicopter crash under suspicious circumstances.

Of course, helicopters crash a lot, relative to other forms of aerial transportation. If an airplane loses power, the wings still provide lift. Not so in a helicopter. In a helicopter, the second the rotor goes off, you fall like a rock—there’s absolutely nothing keeping you in the air. And because a helicopter’s got a very high center of gravity, with the engine and rotor above the cabin, a falling helicopter tends to tumble. That’s why helicopter crashes tend to be fatal. Even so, John’s former business partner “Petr” had a crash that seemed unusually suspicious.

John couldn’t get any details from anyone directly involved. He ended up using back-channels of people he’d met helicopter skiing over the years. Petr, you see, had been killed while helicopter skiing in Alaska. John cobbled together as much data and as many rumors as he could, and—though none of this is official and it should all be taken as unverified, grain-of-salt stuff—this seems to be what happened:

The day of the crash, the weather was expected to get bad. Normally, Petr was fastidious about not skiing or helicoptering in bad weather. And, in fact, every other helicopter flying out of this particular heli-ski lodge on this particular day was grounded, because a storm was coming in. Not Petr’s; it went out and stayed out. Apparently, Petr had decided he would finish the day at a lodge other than the one he’d started at. He was using a substitute pilot because his normal pilot called in sick.

Per its transponder data, Petr’s helicopter made an unscheduled stop somewhere other than the lodge or a ski-run. Then it ascended to the top of a slope, where it caught either a skid or a rotor blade in the snow and crashed. The helicopter’s six occupants survived this. We know they survived because the five who were killed weren’t killed by trauma, but by suffocation. Apparently, the helicopter rolled down the mountain, filling up with snow as it went, and smothering the people inside. The police weren’t notified until some hours had passed, even though the helicopter’s transponder sounded the alarm the moment the helicopter crashed. By the time the cops arrived, the bodies had been removed, so no forensic investigating was done. There seems to have been one survivor, but he isn’t talking to anyone. Litigation is ongoing.

So—that all sounds pretty suspicious. But given the dubious safety record of both the helicopters and the snow-covered, stormy Alaskan mountains, none of this would necessarily make someone suspect foul play. But Petr, you see, wasn’t the first person connected to John’s story to have died under unusual circumstances.

The story John wanted to tell was about he and Petr going to Russia in the 90s, during the lawless decade between communism and Putinism. They made some very canny investments, fended off some death threats, and briefly got share-holder control of one Russia’s most powerful, most profitable energy companies. This is an energy company that may or may not have had its natural gas pipeline in the North Sea blown up recently, under suspicious circumstances. People connected to this company, and to its subsidiaries and direct competitors, have been dying at such a prodigious rate that they’ve taken a starring role on a Wikipedia page titled “Suspicious Deaths of Russian Businesspeople.” A quick Google search will give you results like, “Mystery as fifth Russian Gazprom-linked executive found dead in his swimming pool” (The Independent), “At least eight Russian businessmen have died in apparent suicide or accidents in just six months” (CNN), “Here are the Russian oil executives who have died in the past nine months” (The Hill), “A Wave of Mystery Suicides of Russian Gazprom Executives” (Warsaw Institute), “Another Russian Executive with Ties to Gazprom has been found Dead” (Fortune). Et cetera. So John had reason to worry.

He had a similar reason for wanting his story fictionalized into a novel, instead of telling it himself non-fictionally. Not everyone involved with John’s story wants to be connected to it in print. I can’t imagine why. But I will add, for the record, that the novel is NOT about Gazprom. It’s fiction. How much or what parts of this fiction are based on real events is a secret that will die with me. A long, long time from now, I hope. When I’m old and gray.

So anyway, John happened to have read a couple of my novels and liked them. He made me an offer I couldn’t refuse, which was “how about flying to the Bahamas on my private jet so I can tell you a really cool story?” Much like Ernie Pyle landing on Omaha beach or George Orwell going to Catalonia, I went to John’s estate in Nassau and listened to what he had to say. By the time he was through, I knew it would make a fantastic novel, but there was one important question I had to ask him: “So, if I write this story, is someone going to murder me?”

John shook his head. “No. Definitely not. The Russians never kill Americans. Well, almost never. It’s very unusual. Anyway, I don’t think an American writer’s been killed since —–. Funny, I used to talk to him about this stuff too, when he was covering business in Russia. Have you read ‘The Ghost’? About a writer getting killed? There was a movie. Pierce Brosnan, Ewan McGregor. It was good.”

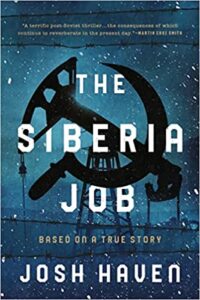

Anyhow, the novel I wrote after our conversation, called The Siberia Job, is out now. I guess this piece is a slightly long-winded way of saying that, if the launch doesn’t go well, I too would like to be played in an eventual movie by a young Ewan McGregor.

***