In 1857, British scholars held a contest to decipher the inscriptions on a 3,000-year-old clay artwork. Today, this would be considered a rarefied pursuit, but in Victorian London, the event enjoyed a keen audience. Mid-19th century Britons were besotted with the distant past, their fervor stimulated by remarkable objects from since-vanished civilizations, which were being pried from the earth in the Middle East. Archaeologists became some of the country’s most famous people. When a London exhibition hall showcased “a fanciful reinvention of the royal palace” in the Assyrian city of Nineveh, attendance topped six figures, Joshua Hammer writes in his new book.

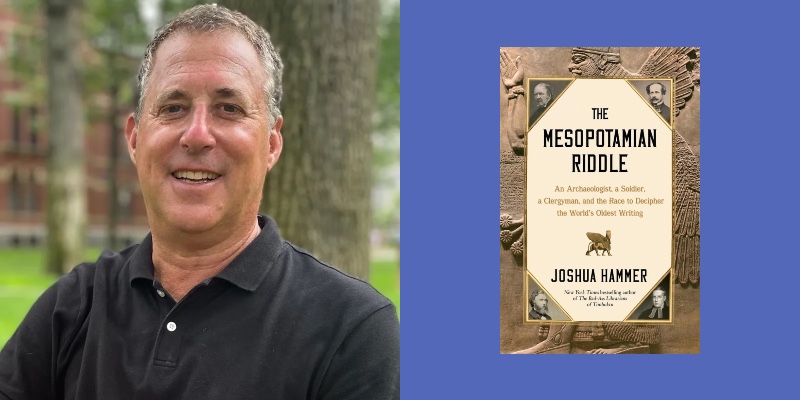

Hammer’s The Mesopotamian Riddle: An Archaeologist, a Soldier, a Clergyman, and the Race to Decipher the World’s Oldest Writing is about an important intellectual breakthrough—and the thievery that coincided with it. Like his bestselling The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu, Hammer’s latest alights on the intersection of adventure and cultural history, explaining how enthusiasts unlocked the mysteries of the Assyrians’ “wedge-based script” and chronicling the British Museum-sponsored “looting” of art and other items from the region.

From his home in Berlin, Hammer discussed his trio of very different protagonists, his immersion in languages no one speaks, and the controversy over Western museums’ ownership of artifacts stolen from other countries.

There was lots of interest in archaeological discoveries and historical mysteries in England at this point. What prompted this?

In 1822, a Frenchman named Champollion declared that he had cracked the Rosetta Stone. That caused a tremendous amount of excitement. Pompeii and Herculaneum had been excavated the previous century, and archaeologists began to explore Egypt in a big way in the early 19th century. So you had these two tracks—a fascination for decipherment and a growing interest in archaeology.

Who were the Assyrians? In the mid-19th century they had a pretty combative reputation. Has that changed?

All you have to do is read these inscriptions from kings like Ashurbanipal (7th century BCE). You don’t really encounter the degree of gore in other ancient civilizations that you find in Assyria. Some Assyriologists, as I mentioned in the book, argue that this is a fairly one-dimensional view of Assyrians, that they were actually contributing great writing, science, art. But I don’t think that the reputation of being a highly aggressive militaristic empire is particularly misapplied. Conquest through massive killing, basically.

Who are your protagonists?

One is Austen Henry Layard, who kicked off the Assyria fascination. He was a middle-class Brit, apprenticed to a prosperous uncle who had a law firm. Layard hated the law firm. Opportunity came along for him to go to Ceylon (Sri Lanka today) to start a law career or work at a coffee plantation. He elected with another Brit to travel overland.

By horse, for a year, as you write.

That was the idea, much of it through the Ottoman Empire, and then Afghanistan and India. This is a fairly wild, untamed part of the world in 1840. To make a long story short, he got to Mosul, saw the mounds of Nineveh, and was utterly transfixed by them. There was no trace of any civilization, just these vast mounds in the desert that had never been excavated. He made his way back four years later. He had managed to get the sponsorship of the ambassador to Constantinople, who gave him enough money to hire diggers. Within a couple of months, he had begun uncovering the lost civilization of Assyria.

And he becomes one of the most famous men in England.

Very quickly. He started digging in 1845. By 1848 he wrote a huge bestseller. The artifacts he was digging up were beginning to make their way to London, incredible bas reliefs and monoliths that were put on display at the British Museum. Assyria fever took off.

Layard had a working relationship with your second guy.

Henry Rawlinson came from a much more affluent background than Layard did. He was recruited by the British East India Company to become an officer in India. Found it kind of boring. But he got a break and was recruited to go to Persia, which turned out to be a whole different world, much less explored. He was quickly caught up in the ancient civilizations of Persia and became obsessed with ancient writing.

Your third character was maybe the most talented decipherer of all.

Edward Hincks, who never made it out to the Middle East, or the Near East as they called it in those days. He was an academic turned pastor in the Irish Anglican Church. In his downtime he was in his study going through hieroglyphs and Hebrew, and ultimately Persian and Assyrian cuneiform.

He did people like Hincks get a look at these inscriptions? How were they gathered and shared?

There were different methods. Rawlinson started off by climbing up this incredible cliff in northwest Persia, where there was a set of bas reliefs and cuneiform inscriptions written in the Persian language. He basically stood on a ladder for months, with a pencil, sketching these characters. And there was a more sophisticated method that was pioneered by a Prussian archaeologist named Lepsius. He developed this method of putting up what was basically papier-mâché, pressing it against the inscriptions on stone and coming away with images.

Meanwhile, as you said, some of these pieces are cut out of the earth and shipped off to London.

A lot of these inscriptions were carved into stone and found in these ancient palaces, then essentially just taken off the walls. They were kind of thin gypsum alabaster panels essentially plastered onto mud brick palace walls.

And there are clay pieces. What do they look like?

They have tiny symbols that are dug incredibly densely onto these clay cylinders. You can tell the annals of a King’s life on a single cylinder. Amazing miniaturization.

You’re writing about logograms and phonetic characters and “silent determinatives,” symbols that might precede a king’s name. How did you make that accessible but also exciting? I’m guessing that was maybe the most difficult part of the book?

Absolutely, I labored over that. Fortunately I found my way to a couple of Assyriologist linguists and just spent a lot of time with them on Zoom, emails back and forth, a lot of questions, lots of materials sent to me—just trying to get the fundamentals down. There was no way I was going to be able to read this language, but I wanted to at least have a grounding. Rawlinson wrote about being at the point of despair with his decipherment. That’s kind of the way I felt a few times.

How should we think about these pieces at the British museum and other institutions given that theft built part of these collections?

It’s a tough one. The old colonial argument was that people in these countries can’t be trusted to care for their art and antiquities. Now, of course, a lot of these countries are hiring some of the great architects of the world to build these magnificent museums. More and more of these countries are offering a strong argument: We’re every bit as capable as these Western colonial powers that stole these things from us.

But as I write about in my epilogue, in northern Iraq ISIS destroyed everything in sight. And you think, what would have happened if Layard had not extracted some of these great treasures? They would have all fallen victim to this radical Islamic terrorist group. The British Museum does offer this incredible location that millions of people can visit.

On the one hand, you’re sympathetic to the positions of countries that want this stuff back. On the other hand, (the British Museum) is a great collection point for the world.