In the fall of 2014, my mother delivered dozens of books to my new home in Boston. I intended each to be signed by Joyce Carol Oates, who I learned would be speaking down the street from me at Brookline Booksmith—the author I believed had saved my life years ago. Being from a hamlet in South Carolina, I never thought I’d have the chance to meet the legend. This is why I took every book by Oates with me, and why the event organizer moved me to the back of the queue.

When I unloaded the books neatly across the signing table, Ms. Oates fixed her eyes on me with a knowing look. “You are a writer,” she said, like a gypsy in a Sam Raimi film, so knowing in what she declared. Her certainty in this statement is something I think of too often. But if you have read her work, there should be no surprise with how she made this declaration: there is a certain truth in everything Joyce Carol Oates writes.

Who is Joyce Carol Oates, and why would she be featured on a website along with modern masters of crime fiction, horror, and thrillers? Given the status and respect she receives in the literary world, it’s easy to forget she has been a master of writing these genres long enough to be contemporaries of writers like John Updike and Gillian Flynn.

While learning about her life is easily accessible, here are a few key points, abridged: Oates was raised in upstate New York, which affects much of her writing; graduated valedictorian from Syracuse, and later received a masters from University of Wisconsin in Madison. Early on, she got attention for the gritty realness of her work, acclaimed for how she captured the worlds of young women in ways her male contemporaries could not.

With time, her stories and novels would establish Oates as a master of experimentation in genre and form. While many are often intimidated by the prolificity of her oeuvre (over a hundred novels, stories, plays, etc), she has gone on to receive much acclaim for her work, including but not limited to: the National Book Award, the Los Angeles Book Award for Best Mystery, a number of Bram Stoker awards honoring her horror fiction, along with countless other awards including being a five-time finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in fiction.

Her work is often based on true crimes, from her opus Blonde to the claustrophobic Black Water, as well as Zombie, My Sister, My Love, her story, “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been,” among others. Ms. Oates’ fans will most often define the writer by the book of hers which irrevocably changes their lives in ways they never thought possible.

At sixteen, I was making my weekly two hour trip each way to see a psychiatrist in Charleston, SC. At the time, I’d been written off as essentially untreatable, too complicated to work with, a patient medicine wouldn’t help and whose therapy was considered largely ineffective. In truth, I was often misdiagnosed likely because we only met for eight minutes after every four-hour drive, in which I was given poor advice during meetings where I was rarely listened to.

Distressed, I pulled over at a bookstore meaning only to browse, my mother always warning me I had too many unread books at home. I didn’t think I could catch my breath after accidentally hearing that word spoken between my psychiatrist and another professional: untreatable.

It was when I saw the newly released My Sister, My Love, that I was able to finally quiet my mind for a moment: the dust jacket, the pages. I did not hesitate in buying the book, somehow knowing before I read the first pages it would function as a sort of balm for me. I’d tried for years to find some understanding in the books of suicidal poets and novelists.

However, it was Oates’ belief in survivors which changed me. Her characters persisting through the worst sorts of suffering helped me understand the importance of not letting life stop you, whether that means an external predator or the brain you were born with. You may not always win the battle, but what seems important to Oates: keep trying: push, and push hard.

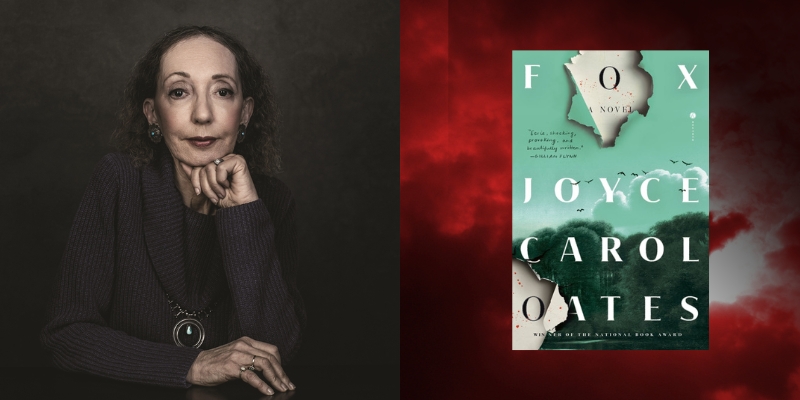

Ms. Oates’ most recent novel, Fox, depicts an alluring male teacher and child predator who is found early on in the novel, ripped to pieces in his partly submerged car. Over the course of the novel, the reader learns of Fox’s victims, the adults who fall for his charm, the few who see through his charming facade, and the character or characters capable of destroying him.

You might wolf Fox down, given it is one of Oates’ most compelling books to date: an endlessly readable opus which can be brutal at times. Oates experiments more with form and style than in most crime novels, while providing enough plot and suspense to obstruct the boundaries of traditional literary novels. This the JCO brand, and there’s always more of it.

*

Matthew Turbeville: Ms. Oates, I am so honored to speak with you. On a personal note, your work has guided me through the absolute hardest times in my life, like my junior year in high school when I read My Sister, My Love, and it truly did save my life. Or, even with Fox, your brilliant and most recent novel, I must have devoured it while I was in the hospital for a bad case of pneumonia late last year, and it was so amazing.

What catches your interest when writing a novel or story? I know so many of your novels are loosely connected to true crimes—Black Water, Blonde, My Sister, My Love, etc—and there are so many others that seem to be at least tangentially connected in ideas or even moods, but what grabs you first, and what drives you through?

Joyce Carol Oates: This is such an essential question!—but what is the (honest) answer?

In some instances, I can pinpoint more or less specifically the moment I felt a sensation of “inspiration”—I think these moments are visceral, in fact; but often, the answer is lost in a welter of numerous causes, as a river, especially a long wide treacherous river, is fed by many tributaries, & where it ends is considerably different from where it has “begun” high in the mountains.

So, my novel Blonde sprang from a mere spark of inspiration when I was, sometime in 1998 in the Princeton Public library, a particularly welcoming and attractive public library only one block from Nassau Hall, Princeton University, I must have been turning pages in a book of American history with many photographs, for no reason I can now recall, for surely I should have been busy with myriad other matters, when a small photograph caught my eye—it was of Norma Jeane Baker, aged sixteen, a high school girl at the time, with brown hair, a sweet open hoping face, very pretty but not at all glamorous; reminding me of girls with whom I’d gone to school, and of my own mother who was born just a few years before Norma Jeanne (born 1926).

I wanted to explore the consciousness of a (male) middle-school teacher who exploited his vulnerable students to enhance his own deeply flawed being.Inspirations for other works of fiction were often equally capricious—though I had been reading, like most Americans, about the scandal of Senator Ted Kennedy at Chappaquiddick & the unfortunate girl he had abandoned to drown…but it was probably 20 years before I wrote Black Water, which began as a short story. My Sister, My Love is (of course) inspired by the notorious Jon Benet Ramsey—notoriously poorly investigated by local Colorado police—but also by a wish to write about the experience of one who is “tabloid famous”—a captive of the media as the narrator is.

Inspiration for my new novel Fox is partly local, geographical—I often walk/hike in a bird sanctuary/ Green Space near my home in Hopewell township, NJ—it is like the setting in “Fox”—which is near the Pine Barrens in south Jersey. Often one sees, high overhead, circling, turkey vultures… Also, I wanted to explore the consciousness of a (male) middle-school teacher who exploited his vulnerable students to enhance his own deeply flawed being.

MT: Some have said Fox is a response to Lolita, but I feel in many ways it could work just as well in conversation with so many other books. I almost see it as a closer (although, I do hope there will be more, really) to a loose trilogy of books regarding the often unseen or forgotten act of violence upon multiple women, as afflicted by men in different areas of society—and in different time periods, also.

What do you feel brought about each of these books, and in such a close publication period for you?

JCO: Yes, it is likely true, though I had not thought of it until now, that Babysitter, Butcher, and now Fox form a kind of trilogy: women & girls victimized by malevolent men, in the first case coldly and with premeditation, a “charismatic” man preying upon the wife of a millionaire businessman in a Detroit suburb in 1976; in the second, a physician-surgeon preying upon helpless female “lunatics” in Trenton, NJ in the 1840s—1850s, to establish his reputation as a pioneer in “gyno-psychiatry”; in Fox, the charismatic middle-school teacher who behaves so cruelly to young impressionable girls, though without much consciousness of how deeply he is wounding them, since he is a superficial person himself.

It is significant that Francis Fox strongly disapproves of Lolita“—he is a pedophile too but his area of erotic interest is girls older than ten or eleven—Fox’s girls are in the Balthus age-group, prepubescents of twelve, thirteen, fourteen—no younger & no older. Fox imagines himself an aesthete set beside cruder Humbert Humbert; ironically, Fox reveals himself as something of a puritan.

MT: Why do you feel Mr. Fox met his end in order to complete the novel—his end was violent, his discovery strange, but who was it meant for—one of the characters, the readers, you? Do you ever find yourself with a character like Mr. Fox, who may need to die brutally, or may deserve redemption, and you grant a certain ending to the character in question to satisfy yourself, and not for the story, and not for the reader?

JCO: Basically I am a formalist, and this novel is a mystery: as the reader is invited to assemble parts of a mystery, or a work of fiction, so the disparate “body parts” of the murder victim are assembled to comprise a story with a clear motive, a chronology, a purpose, and an ending.

If you are a formalist & you are writing a mystery, you are inspired to present the story in itself as an unfolding mystery, like life; the way into Babysitter, also, is by a shifting of perspectives, including chronological perspectives: in both novels we move forward in time but also move backward in individual chapters that are flashbacks, moving forward in the past simultaneously with the forward-movement of the story.

This sounds more difficult than it is—it is a natural way of storytelling—when you read a novel so structured, you read it seamlessly, knowing that it is moving forward in time, & that it will come to an end—(which is already known to the author, but not to you as the reader).

In a mystery, especially involving detection, it is important to have a clearly explained “solution” to the mystery. In Fox the final chapter is the explanation, though the confession might be questioned in its details, which might include confabulation, essentially the ending is THE ending, & it is not ambiguous.

A distinction between genre fiction and “literary” fiction is this: genre fiction abides by certain unstated rules, “literary” fiction does not. A massive novel by a postmodernist writer might trail off in irresolution or loop around to its beginning, as in Finnegans Wake–a literary novel should be unique.

Fox is a genre novel imagined as a postmodernist experiment with genre—as Blonde is a postmodernist “bio-fiction” narrated by the posthumous Blonde Actress who is seeing her life rush by her on a movie screen. Babysitter is an experimental sort of “thriller” in which, it sometimes seems, the narrator is Hannah herself, as she lies (dead, awaiting dissection for an autopsy) on a gurney in a morgue.

To me, experimenting with genre is particularly exciting because the genre-story is complete in itself, as a story, with a definite ending; while the “postmodernist” reading might be something less evident, like a posthumous narrator.

(In a sense, all narrators are “posthumous”—they are telling a tale, sometimes a very complicated tale, that has ended, & they know the ending; but the ending must be withheld from the reader until the literal END.)

MT: What are the things that give you pause before starting a novel or story? Do you ever fear a similar novel having been recently written, or a novel being too much for the public, or not turning out how you want? Do you ever give into fear, or have a way of pushing past it?

JCO:This isn’t ever an issue with me. I walk/run every day—I am continually imagining a dramatic scene playing out in my head: a chapter in a novel-in-progress, or a short story. These are all original with me, springing from a setting, a photograph, a sudden sighting, a memory.

MT: Have you ever found yourself afraid of any of the characters you write about?

JCO:No! I am probably akin to Nabokov, as a formalist at heart.

MT: Megan Abbott once advised me to always flesh out every character I write, even the antagonists, and never portray them as wholly black or white (this might not be the exact wording, but the sentiment is there). How do you approach developing characters you may not readily identify with—like in Zombie, or characters like Jules from them? Do you care whether readers like the characters in your work?

JCO: It is obvious that all human beings are complex. It would not seem to me necessary to even ponder this. It is not important whether anyone “likes” Macbeth, Lear, Raskolnikov, Captain Ahab—only that the stories that embody them are sufficiently alive, lifelike, convincing, universal.

MT: How often do you consider the way that violence plays a significant way in your work? So often this could be extreme violence, even multiple acts of violence, and occasionally the stories where violence is spoken of from long ago in the past or far off screen, but never shown (think of the serial killer from The Gravedigger’s Daughter). What draws you to violence personally, as a writer, and as someone relating story after story to an audience?

JCO: Most of our lives, if we explore the past, are related to violent acts, crimes—long ago, in another generation, perhaps. That is true in my family—both sides of my family. (My father’s side of my family is explored in The Gravedigger’s Daughter—the adventures of my grandmother, my father’s mother, in upstate NY many years ago. To survive was the goal–& they did survive.)

I am fascinated by the ways in which, as Henry James once observed, what is “bane” for some persons will be “bliss” for others—a bitter sort of entanglement, as of deep knotted roots in the soil, at the base of enormous trees, hidden to the ordinary eye.

MT: When you write a novel based on an actual crime, does it matter to you if you are able to reach a conclusion to the mystery the way the truth might be revealed later to the real-life event if it hasn’t already been concluded at the time? What are the other reasons behind providing an answer to crimes that can often seem lost in time?

JCO: In Mysteries of Winterthurn there are three mysteries, two of which were inspired by “unsolved” American crimes: the first, the Lizzie Burden case; the second, a mystery known as “The Minister & the Choir-Singer”—setting New Brunswick, NJ in early decades of the twentieth century.

One of my novels closest to my heart, Mysteries of Winterthurn is at once a portrait of an old-time Sherlock Holmes-type detective, the exceptionally handsome and “good” Xavier Kilgarvan, and a critique of old-time mystery writing, especially the kind of nostalgic crime writing that dwells upon famous cases, brooding over the “true identity” for instance of Jack the Ripper, or romanticizing sordid events through a scrim of poetic writing.

But I wanted to create, in this detective, a form of the writer, who works through frustration, defeat, misery, self-doubt, every kind of resistance, works doggedly & daily, even hourly, intent upon the solution—the way out—finally completing the project: the detective solves the mystery, the writer solves the problem of the work of fiction, by managing to complete it. The similarities seem to me important: the public knows/cares only about the solution, to the mystery; & to the book that is finished—the product.

No one can gauge how much effort goes into what looks, or should look, like a smooth finished product. Glance at Ulysses, for instance, & you will see a finished product, but have no sense of the seven years, and more, of effort, so many visions & revisions, into which James Joyce poured his heart. Once in, you sink or swim—you must swim, or you will sink—the reward is survival: you have survived!

I am drawn to narratives in which the sympathetic & perceptive reader knows more than the protagonist might know: in Winterthurn, in the final chapter, in which the detective falls in love, it is intended that the reader know who the “murderer” is—even as the detective is in denial about the identity of the murderer/murderess.

MT: Does it mean anything, or matter to you, that many insist you are only a literary writer, instead of also being a crime writer (as well as other genres)? What do you think the real difference is between these two genres? Is an author considered more likely to be telling the truth in their fiction depending on the kind of story they write?

JCO: Really? I have not the slightest awareness of the “many” who “insist that I am only a literary writer….” This is all news to me but not surprising perhaps for I try to avoid reading about myself if I can help it!

(If reviews are sent to me by editors or friends, I might read these, but I never/ever seek anything out about myself, as many of my writer-friends also avoid such rude intrusions. To name just two, Richard Ford & Jhumpa Lahiri, who avoid literary reviews & gossip, as I try to do also.)

MT: How do you approach blurring different sorts of stories together, incorporating not only crime fiction, but also elements of horror and science fiction into your writing?

JCO: Gosh—I am not sure how to answer this except at enormous length….I fear I have already written too much in this interview.

MT: Black Water is such a brief novel which speeds toward the end of a woman’s life after a short, indeterminate amount of time, where we see so much of the protagonist with so little said, and where the reader experiences more anxiety, fear, and the stomach-churning need to be away from something—not only a book, but a reality you’ve created.

Do you mind talking about how you build suspense in your writing, especially in such a condensed narrative as this where it seems you made every single word count? Did you ever want to keep going with it, have an epic the size of Blonde?

JCO: As I had said, I think of myself as a formalist, experimenting with form, and Black Water has the structure of a ballad; an old-time English & Scottish ballad with a title like “The Elf King” or “The Elf King & the Maiden”; in the ballad, a story is told through repetition, including incremental repetition; at the end of each stanza, a line is repeated—”And the black water filled her lungs, and she died.”

So through the short chapters of the novel, until the end—the final statement of the final line—”And the black water filled her lungs, and she died.” The structure allowed me to present familiar material in an unfamiliar way, from the perspective exclusively of the drowning girl, the victim; the Senator, on whom ninety-nine percent of press attention was focused at the time of Chappaquiddick, is at a distance here; the girl-victim of the Elf-Knight is just as important as he is, perhaps more important, in this telling.

So, an epic could not be construed around this person: she has not the public stature of “Marilyn Monroe”—the iconic Hollywood equivalent of Moby Dick: individual but also emblem.

MT: What book or books have you decided to read next, what book did you read last, and what book would you recommend to me or to anyone, for any reason? What book are you working on currently? Can you talk about the work with us to any length?

I am drawn to narratives in which the sympathetic & perceptive reader knows more than the protagonist might know.JCO: I have just—literally!—finished a lengthy review of Caroline Fraser’s Murderland—for New York Review of Books—so I will ask you to wait for that to appear. Thank you for your excellent questions.

MT: I wanted to say thank you so much for agreeing to speak with me today regarding your work and the genres you fit into. I want to add that I don’t actually believe you need to completely fit into one genre or another—especially you, Ms. Oates. You push at the seam of things, demanding to make stories your own by refusing to stay within perimeters set up for you.

I hang onto the idea of reading the novels you write over the years to come, and how far you will stretch yourself and your talents to produce work that shifts how we think and illuminates so much about what we believe we know.

***