Joyce Carol Oates brings me joy.

I first met the author at a book signing. We had traded tweets about our pets beforehand, and she’d given me a story for my Anthony-finalist anthology Protectors 2: Heroes. But when she saw me, she leaned over to her friend the artist and author Jonathan Santlofer and exclaimed, “have you met Thomas? He’s a lovely kitty man.”

I am a large and hirsute man, a “temperate yeti,” in the parlance of a witty friend, and the “kitty man” nickname brought a few laughs. I have since embraced it; as a big goon with a nose smashed flat from fight training, it’s been a good icebreaker at readings.

We’ve been friends ever since, and Joyce Carol was gracious enough to submit to this interview for CrimeReads. As one of the most eminent American authors she should need no introduction. I won’t attempt to condense her impressive body of work or stun you with a roll of titles, but here are a few highlights of her accomplished writing life:

As one of the most daring writers working (in my opinion), she began writing regularly when she was fourteen, and was gifted a manual typewriter; she won a Scholastic award in her teens, the National Book Award for her novel them at age 32, and was given the National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama in 2010. With her husband Ray Smith, she published The Ontario Review literary journal until his death in 2008. She writes in many genres including Gothic and crime; if any would doubt she is a crime writer at heart, one of her formative literary moments was after reading the horse-whipping scene in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, which defined her duty as a writer: “Uplifting endings and resolutely cheery world views are appropriate to television commercials but insulting elsewhere. It is not only wicked to pretend otherwise, it is futile. If all a serious writer can hope to do is bear witness to such suffering, and to the experience of those lacking the means or the ability to express themselves, then he or she must bear witness, and not apologize for failing to entertain, or for “making nothing happen”—in Auden’s derisory phrase.” (This is from Celestial Timepiece, a web archive of her work run by Randy Souther, a great resource for all things JCO.)

And despite this rather bleak outlook, she makes wry jokes on Twitter about dinosaur hunting and from the perspective of her cat Zanche. (She has also penned a couple of children’s books about her cats). If you see her speak at a literary event, Oates is sharp off the cuff, but also seems to have a direct channel to the wonderment of childhood. This informs her writing when her characters must confront the most primal fears of children, such as “does my family really love me?” and other questions so terrifying to contemplate, explored in two of the three books she has had published so far this year.

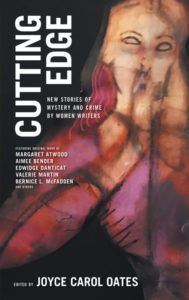

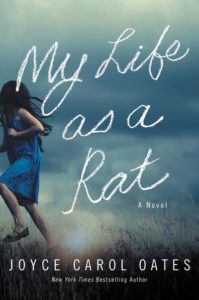

I have read Pursuit, a thriller from Mysterious Press, and The Triumph of the Spider Monkey, a re-release from Hard Case Crime. My Life as a Rat, the story of a young girl who inadvertently informs on her family after they commit a brutal racial crime, awaits on my shelf beside my favorites: We Were the Mulvaneys, about the exile of a victim of a sexual assault and her family from their once-beloved hometown; the revenge romp Foxfire: Confessions of a Girl Gang, and the epic fictionalization of Marilyn Monroe’s life, Blonde. I’ve read a dozen of her books and only skimmed the surface. When I met a writer who said he “couldn’t read her style,” I had to ask, “which one?” Her voice is strong, but spans many octaves. Her latest project is Cutting Edge: New Stories of Mystery and Crime by Women Writers, from Akashic Books, with original stories from Margaret Atwood, Edwidge Danticat, Steph Cha, S.A. Solomon, Cassandra Khaw, S.J. Rozan, among others, which looks to be the crime anthology of the year.

Enough gushing from the kitty man. The interview:

(This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.)

Thomas Pluck: The first novel I’ve read of yours was Zombie, which stunned me. I can still recite passages from it. So it was interesting to read an earlier killer story, The Triumph of the Spider Monkey. This one felt more sympathetic to the subject. Bobbie Gotteson is a rock ‘n roll wanna-be, the perfect picture of fragile masculine ego, a haunting and pathetic character, a survivor of abuse. I couldn’t stop seeing that famous mug shot of Charles Manson in the place of his face, bewildered and animalistic. What inspired the story, and do you think it will still resonate in the age of internet celebrity and endless mass shootings? They are similar, media-obsessed sociopaths…

Thomas Pluck: The first novel I’ve read of yours was Zombie, which stunned me. I can still recite passages from it. So it was interesting to read an earlier killer story, The Triumph of the Spider Monkey. This one felt more sympathetic to the subject. Bobbie Gotteson is a rock ‘n roll wanna-be, the perfect picture of fragile masculine ego, a haunting and pathetic character, a survivor of abuse. I couldn’t stop seeing that famous mug shot of Charles Manson in the place of his face, bewildered and animalistic. What inspired the story, and do you think it will still resonate in the age of internet celebrity and endless mass shootings? They are similar, media-obsessed sociopaths…

Joyce Carol Oates: Seen from a distance, “Spider Monkey” was a gesture of youthful rebellion, and seeing it now, forty years later, reissued, with a radiantly lurid pulp cover by legendary artist and illustrator Robert McGinnis is a total—quite wonderful—surprise. It is an “uncensored confession” of the sort of mass murderer/ serial killer who has come to dwell permanently in the American psyche, a fecund Collective Unconscious roiling with revulsion, fascination, envy, and dread. Inspired by the phenomenon of the Charles Manson cult murders of August 1969, and the lengthy trial that followed, it explores the aftermath of that period in American history when the ebullience and youthful idealism of the Sixties had run their course—the Greening of America followed by the Conflagration of America (Vietnam War/ youthful fury and rebellion against that war; Nixon/ Watergate; drugs, riots/ “urban disturbances”; assassinations). In this moral chaos, Bobbie Gotteson is a hapless victim, a perverted “son of God” (as Manson was a perverted “son-of-man”)—like the historical Manson, he was abused as a child; unlike Manson, he never imagines himself as a savior / con man manipulating others, and his affect is naive, not calculating.

TP: In an older interview, you said you “don’t have a personality,” that you are “transparent.” That felt familiar to me, because I often feel like an alien naturalist hiding among humans to observe them. Do you think these are side effects from being a writer, with our relentless observation?

JCO: I don’t know how to answer that—I think it may be a sensation more understandable in a playwright who doesn’t seem to “inhabit” a narrative quite the way prose writers do. In a novel I am often more interested in illuminating & tracking a dramatic sequence of events—following a sort of trajectory of action—that throws off sparks into the lives of individuals, often changing them irrevocably. Of course, we also write introspective prose from the perspective of characters who resemble us, at least outwardly.

TP: How do you keep track of all your work, at different stages of completion? Your journaling is legendary—in another interview, you said you had 4000 pages—do you also keep copious notes on these ideas as they develop?

JCO: I don’t have any difficulty remembering any projects or characters. They are all just—somehow—there, in their own compartments. But I usually concentrate on one project at a time, & immerse myself in it totally.

TP: I envy your powers of recall. I’m deep into Blonde, considered one of your masterpieces. I was never a fan of Marilyn Monroe until a friend told me to watch The Misfits, and I caught a hint of the depth and talent she had, that was never respected by Hollywood. Now I’m watching all her movies, as I read. The book is a whirlwind, an epic exposing the American myth of our Love Goddess, and you refer to her in fairy-tale terms. The Fair Princess. The Dark Prince, who is her father, the lover who understands her, the unattainable, and the deadly Erl King—like Arnold Friend in “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?”—all in one. What drove you to write this epic?

JCO: I saw a very touching photograph of Norma Jeane Baker taken when she was 16—brunette, pretty but not glamorous, very sweet & hopeful—looking—not unlike my mother & girls with whom I went to school many years ago. Girls whose great hope was to be loved—married, & to have children. I felt such sympathy for her, who would be dead in twenty years, as an American “icon”—who made millions of dollars for others (men) but not so much for herself. The project began as a short novel, a post-Modernist ironic tragedy that would end with Norma Jeane’s new name: “Marilyn Monroe.” But when I came to this ending, I saw that the great story lay ahead—& reconstituted the material as an epic, with many sub-themes that allowed me to explore obsessions of the era, particularly Cold War politics.

TP: I feel like we sacrifice starlets like children to Moloch. There’s a dangerous Puritan duology in American culture, the whore/Madonna complex perhaps, where we love these young women but also want to punish them, see them destroyed, resent their beauty, and the power we think it gives them. Foxfire: Confessions of a Girl Gang predates the #MeToo movement, high school girls taking revenge on the gropers, molesters, and worse in their town. With women speaking out more freely now, have you considered revisiting Foxfire to write a sequel?

JCO: Thanks, Tom! I loved that novel & I should revisit, yes. Perhaps the novel will be reissued. It may be in some publishing limbo in which an old publisher does not want to republish, or to relinquish copyright.

TP: I am consistently awed by how well you portray the inner life of the insecure male. From the “Ex-Athlete” in Blonde, to Gotteson, to the vengeful brother in We Were the Mulvaneys, you write with an empathy for men that most male writers of your generation lack when writing women. (I followed your recent Twitter discussion about Philip Roth with interest.) Has your love of boxing given you an inside view of the male mind, as “one of the boys” who enjoys the violent sport?

JCO: Again, hard to know. I don’t discriminate “against” men simply because they are not women…. Men are individuals, & individuals are complex. But we are all impressionable, for good or bad.

TP: Do you have any favorite boxing novels?

JCO: Leonard Gardner’s Fat City is a droll minimalist vision of failed lives, a longtime favorite. (It had seemed to me that no one had shown interest in writing about men who happen to be, to a degree, boxers, but who are fully defined in other terms, as in my domestic-realistic novel You Must Remember This.)

TP: I liked Fat City, and Thom Jones is a favorite. I enjoyed Willy Vlautin’s Don’t Skip Out On Me, which I recommend highly. Your newest novel is My Life as a Rat, about a girl who informs on family members who commit a race-driven murder. The line, “You think your parents love you, but is it you they love, or the child who is theirs?” is a great example of how you punch straight for the heart with your writing, confronting the fears we never talk about. Was this one inspired by a true event? Or is it wish-fulfillment?

TP: I liked Fat City, and Thom Jones is a favorite. I enjoyed Willy Vlautin’s Don’t Skip Out On Me, which I recommend highly. Your newest novel is My Life as a Rat, about a girl who informs on family members who commit a race-driven murder. The line, “You think your parents love you, but is it you they love, or the child who is theirs?” is a great example of how you punch straight for the heart with your writing, confronting the fears we never talk about. Was this one inspired by a true event? Or is it wish-fulfillment?

JCO: Hmmm! Any story of being rejected by parents, of losing parents’ love, probably has some autobiographical genesis, if but a fantasy terror of being lost. I still have nightmares of being “lost”—very upsetting, depressing—so I would say that the genesis of this story, like that of We Were the Mulvaneys, must be very personal; though in fact my parents were loving & supportive, & my father’s mother, my Jewish grandmother, was one of the abiding guides of my emotional life. But I did have—I have—a friend who was cruelly rejected by her parents, under very different circumstances, & when I learned of this I felt a strong identification with her, & sympathy for her. In a way, perhaps this is her story conjoined with my own.

TP: I remember you mentioning such a friend in The Lost Landscape. You never shy from the controversial, and you’ve been chided for it on social media. It feels like Twitter exists to channel outrage, but I can’t leave it. I’ve been online since the web existed, and I’ve chatted with people electronically for over thirty years. Sociologist Sherry Turkle first thought the internet would bring people closer, but now describes it as “being alone, together.” What keeps you tweeting?

JCO: People like you, Tom! Your tweets are smart, funny, thought-provoking & informative. And there are many others in that category. And there is the other vast & winning CATegory. Need we say more?

TP: I love your dry sense of humor, and it amuses me how many people don’t get the joke. Like when you posted the photo of Steven Spielberg in front of the triceratops, and the responders said you had “liberal brain disease.” What are your favorite humorous novels?

JCO: Humorous novels…. I would need to think about this.

TP: I remember you telling me Nathan Englander was very funny, at Montclair Literary Festival. Nowadays writers want to write a book that becomes a TV series, so they can write for television, where the money is. I’m interested in the new Blonde miniseries. What are your favorite shows on television at the moment?

JCO: I’ve much admired “Escape at Dannemora.”

TP: Your latest thriller is Pursuit, which chilled me to the bone. It’s like a Grimm’s fairy tale updated for our time, on the danger of disallowing our loved ones to have secrets… Can you tell us briefly about the genesis of this story?

JCO: I had been haunted for years by the same “vision” that haunts the young woman protagonist—I think it was an emblem to me of the absolutely worst, most horrific & appalling thing that could happen to anyone. Which is why I eventually created an entire short novel about it, and made that novel (unexpectedly, I hope) a tender story honoring marital love. (I know—it sounds virtually impossible in our #MeToo era of terrible men and their enablers to seriously/positively depict marriage—yet all around us are marriages of people who truly love each other.)

I have usually focused on conflicts within the family & marriage—(of course: art is about conflict, unavoidably)—& had wanted to write about a genuinely idealistic young husband in love with a mysteriously wounded/ elusive young wife. So, there are dramatically contrasting marriages in Pursuit—the marriage of Abby & Willem & the marriage of Nicola & Lew Hayman (himself a victim of an absurd war).

TP: We can’t not talk about cats. That’s where we began! Louie says “hello.” How is Zanche? You’ve written from the perspective of a bird stuck in an airport, but have you ever written a story from a cat’s perspective?

JCO: My children’s books are mostly from kitties’ perspectives. And they all end happily with kitties sleeping on little girls’ beds PURRING. (quite a contrast to the sort of endings we are obliged to supply for mainstream adult fiction.) I have written a story titled “The White Cat”—but it isn’t from the point of view of the cat…

TP: I find cats to be a litmus test. I don’t mind dog lovers, but if you don’t like cats, I don’t trust you. Because they rarely abase themselves for our attentions. Have you encountered any cat haters? What are your thoughts on them? What could make someone so heartless?

JCO: What can I say? (Some) people are crazy.