There’s a scene in Bram Stoker’s brilliant novel Dracula that perfectly sums up the narrative’s treatment of beautiful, doomed Lucy Westenra. It’s meant to be lighthearted; just a funny anecdote written by a charming young woman to her dear friend about the day three different men proposed to her.

But when that scenario is scrutinized—three men, all friends with each other, all thinking they’ve got a genuine shot at a yes, and all proposing on the same afternoon—it raises some questions. First of all, my dudes: do you not talk to each other?

Second of all, my dudes: do you not talk to the woman you’re trying so hard to marry?

And the answer to the second question is no, no they do not. Because the Lucy Westenra they love isn’t a person. She’s a perfectly lovely (and fabulously wealthy) blank slate for them to project their own wants, needs, and feelings onto. They don’t actually know or care how she feels. The only thing that matters is how they feel about her. The fact that she might have an opinion on her future doesn’t occur to them. Her own desires never factor into their plans. And it gets Lucy killed.

How do we get from a triple proposal to the decapitated corpse of a hopeful nineteen-year-old girl? Pretty easily. An inability to see Lucy as a person with agency leads directly to her tragic end. I’m mad about it, I’ve always been mad about it, and eventually I got mad enough to write a new ending for Lucy. Let me tell you why.

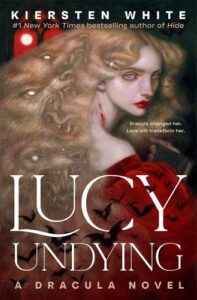

(It’s fine if you haven’t read Dracula in a while. Or ever. Though I do recommend it! I’ll give you the basics here, just like I do in my version, Lucy Undying: A Dracula Novel. My reimagined tale references the events of the original, but with a focus on Lucy and her search for self and love. Unlike Stoker’s compact timeline, Lucy’s new story spans clear to the modern day, including a decidedly 21st century vampiric multilevel marketing cult. Vampires always have been a pyramid scheme, after all. Lucy Undying is gory and funny and deeply romantic. I think Stoker would be pleased we’re still using his iconic vampire as a vehicle for new tales.)

We’ll gloss over the first attacks. Dracula dramatically lands his ghost ship in Whitby, which just so happens to be where Lucy is vacationing with her dear friend Mina. A midnight attack leads to sleepwalking and strange behavior on Lucy’s part, but Mina can’t stay. She’s called to the side of her fiancé, Jonathan Harker, who’s recovering from his own Estate Planning with a Vampire (not quite as thrilling as an interview, but he’s a lawyer, not a reporter).

Lucy returns to London, where the men in her life become concerned with her pallor and general lack of health. Doctor Seward brings in an old acquaintance, Doctor Van Helsing. It’s immediately clear that Van Helsing knows, or at least suspects, what’s going on. But instead of doing something about it—telling everyone that Lucy’s being attacked by a vampire, or moving Lucy to a location that would make it difficult for Dracula to access her—Van Helsing adopts a winking “let’s wait and see” attitude where he constantly hints that he knows exactly what’s going on but does almost nothing about it.

As Lucy is repeatedly attacked, the lack of respect grows more dire. Dracula is drinking her blood without consent but the men are adding their own blood to her veins in the same way: performing medical procedures on Lucy without her knowledge. Each frames donating their blood to her in a borderline sexualized manner, claiming it’s almost like marrying her. To repeat, Lucy does not know this is happening. They never tell her. (Also: what are the odds she was a universal recipient or they were all universal donors? Not likely!)

Meanwhile, Lucy lives in a painful twilight, feeling better only to be plunged back into pain and darkness. Even worse, the heroes regularly drug her—again, without telling her. Her diary entries from this time are deeply sad. She praises the men taking care of her while talking about her confusion and fear over what’s happening.

If the men had been adequate caretakers, perhaps this could be overlooked. Instead, they do the same thing over and over again—fixing the symptoms of Dracula’s attacks, declaring Lucy safe, and then leaving so she can be attacked again. It becomes agonizing to read about. (Both because one feels sorry for Lucy, and also because the narrative really needed to get a move on. I love you, Bram Stoker, I think you were brilliant, but you needed an editor sometimes.) Narratively, it’s almost a relief when Lucy at last dies.

But of course this isn’t the end, because a) vampires and b) the men aren’t done deciding what’s best for Lucy.

Thanks to a) vampires, Lucy comes back from the dead. But she’s no longer a sweet, innocent thing the heroes can project whatever they wish onto. Therefore, she’s evil. Her purity has turned to “voluptuous wantonness.” But Stoker doesn’t stop there in his portrayal of how a woman can become monstrous. Because Lucy can’t have children, she preys on them. Because she’s no longer a virginal woman on the cusp of marriage, she’s openly sexual and tries to seduce the men.

Lucy dies a terrible, prolonged, pointless death because she’s the innocent and silly receptacle of several men’s desire…They decide to kill her, permanently. It’s understandable within the narrative, but this part isn’t: Did you know they kiss her dead body? Gross, but also deeply upsetting. Once they’ve killed the version of her they found so repulsive, they comment on how she’s herself at last. The Lucy they all love. The one who is officially no longer a person, but forever an object.

Lucy dies a terrible, prolonged, pointless death because she’s the innocent and silly receptacle of several men’s desire, while Mina gets to live because she’s serious and useful and already committed to marriage. (Mina’s absence from the end of Lucy’s life can be explained by Mina dealing with her husband Jonathan Harker’s illness, but it doesn’t sit right with me that she wouldn’t check in with Lucy, or that Lucy’s fiancé Arthur wouldn’t bring Mina in when they knew Lucy was dying. There’s not even mention of Mina at Lucy’s funeral. And let’s not get into my actual theories revolving around inheritances and surprise new wills. You’ll have to read Lucy Undying for those.)

I hate the way Lucy is Dracula’s victim, yes, but even more than that I hate that she’s a victim of the possessiveness and incompetence of the very men who claim to be taking care of her. For years, I’ve wanted to give her a new narrative. One rooted in Lucy discovering her voice and her power, that acknowledges Lucy’s joyful loving heart isn’t a weakness but a strength, and, most importantly, that gives Lucy a girlfriend.

Oh, did I not mention that I read Lucy as 100% queer? Let’s go back to that proposal scene. Lucy wrote it all out in a letter for the sole purpose of entertaining Mina. The proposal she actually said yes to—the most socially acceptable one to the future Lord Godalming—is only mentioned as a postscript. That was how little Lucy cared about marrying Arthur. But Lucy repeatedly talks about her time spent with Mina, the laughter and the secrets and yes, the literal kisses that they shared.

That’s part of why it breaks my heart that Mina wasn’t there for her in the end; either Stoker or the characters he wrote couldn’t see the relationship that mattered most to Lucy was the one she had with another woman.

In the end, Lucy Westenra is a fantastic character. She’s funny, she’s charming, she’s tragic. I’m glad Bram Stoker created her. And, despite all my complaints, Dracula is a brilliant novel. But I’m also glad I had the chance to take her from that narrative and give her a new one where she walks through the decades wondering who she is, why she still exists, and whether anyone can ever love her as much as she loves them.

Lucy, I love you. And I hope—unlike those four bumbling would-be saviors—that I’ve done right by you. If nothing else, I gave you a girlfriend at long last. You’re welcome.

***