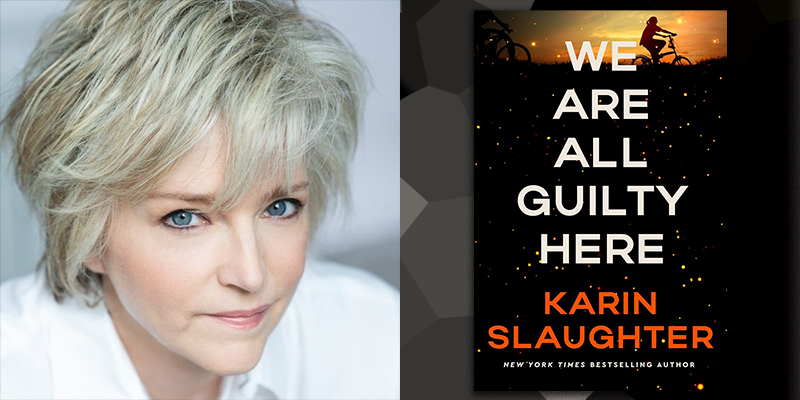

Milestones by nature are cause for looking back, yet New York Times bestselling author Karin Slaughter has her eyes firmly set toward the future.

“I think that’s been a hallmark of my career,” Slaughter says on the publication her twenty-fifth novel. “I always want to write something new and not repeat myself.”

In that spirit, her latest, We Are All Guilty Here (William Morrow; August 12, 2025), serves as the launching point for the North Falls series. The book introduces a new creative canvas while maintaining the keen psychological insights and complex procedural details that characterize her work, which exposes society’s deepest fissures.

“I’m writing for entertainment, but I’m firmly planted in reality,” Slaughter says of the delicate balance between plotting and procedure.

This potent mix of fictional embellishments and factual elements has been another hallmark of her career, which began with 2001’s Blindsighted and also comprises the Will Trent series as well as a scattering of standalone novels and short stories. Cumulatively, the books have sold more than 40 million copies around the globe.

“I got my start writing about small towns with Grant County,” Slaughter says of the series that first introduced her to readers. “I wanted to create something that was larger and more connected to Atlanta and with bigger crimes than you would see in Grant County.”

Enter North Falls. It’s another small town, but within a larger geographical region—and populated by big personalities with even bigger secrets. When two teenage girls disappear during the annual fireworks show, Officer Emmy Clifton vows to bring them home to their families. It’s not just a professional obligation but a personal mission. After all, one of the missing girls, Madison, is the daughter of Emmy’s best friend, Hannah.

“It was a comingling of character and crime,” the author explains of the story’s impetus. “But I wanted to do a lot of world building, and it started with me thinking about Emmy and her life and her relationship with her family.”

The daughter of the town’s stoic sheriff, Gerald Clifton, and a distant and pedantic mother, Emmy was raised in the wake of a tragedy that she has yet to fully understand. With her marriage on the brink of collapse and a young son to raise, she continually finds safety and solace in Hannah, who has always been her family by choice if not blood. But when Emmy fails Madison in a moment of need, their relationship is irrevocably fractured.

“Losing Hannah was in many ways harder than her marriage breaking up because that friendship was the most important relationship to her from kindergarten,” Slaughter says. “[Emmy] is very good at compartmentalizing things … but the loss of Hannah is something she can’t compartmentalize.”

The only recourse, then, is for Emmy to throw herself into her work, sparing no effort in uncovering what became of Madison and her friend, Cheyenne. And the deeper she digs, the more disturbing the discoveries.

“It’s not a great time to be a woman right now,” Slaughter reflects, before pausing to question whether it has ever been a great time to be a woman. “We’ve lost a lot of rights … our human rights, our bodily autonomy, and so it seemed like a good time to talk about the fact that we don’t give young girls time to be young girls, particularly when a crime happens.”

To that point: While the police deem the circumstances of the girls’ disappearance suspicious, rumors about what they may have been involved in immediately arise, thereby diminishing their status as victims—a phenomenon that echoes the real-life news cycle.

“We instantly want to know more about them to decide whether or not we think of them as victims or we think of them as perpetrators,” Slaughter notes. “And you see this a lot, particularly with teenagers who have gone through puberty, where we stop treating them like they’re children if something bad happens.”

And while something bad does indeed happen to Madison and Cheyenne, Slaughter puts focus on the girls’ innocence and naivete, which may have rendered them vulnerable to exploitation but also reveals their underlying human frailty.

“What I wanted to do was give these girls names and feelings and agency,” Slaughter says; consequently, she chose to open the book from Madison’s point of view. “She’s got these dreams of going to Atlanta and meeting a football player and becoming a football wife. To her, that’s very much rooted in reality. It’s the sort of thing you can think when you’re fifteen, but by the time you’re twenty you know that it’s not going to happen.”

Emmy is not so far removed from those tender, tumultuous years that she can’t relate to the girls’ dreams of having bigger lives in a world beyond North Falls.

“Emmy has a line that I really love, where she says: ‘It’s so fucking hard to grow yourself into a woman,’” Slaughter recalls. “And I thought, with Madison starting off the story, I could capture that dichotomy.”

The narrative quickly becomes more expansive, introducing additional perspectives and a seeming resolution before flashing forward twelve years. Another girl goes missing in similar fashion to Madison and Cheyenne, sparking Emmy and her declining father into action—and reaction.

“Nobody likes to be wrong about things. I think police officers can be particularly averse to saying when they’re wrong,” Slaughter says, acknowledging that reticence to engage with the public in a transparent manner can cause distrust. “There’s sort of a cognitive dissonance that takes place with some of these police departments, which is why it’s good to have outside scrutiny.”

In another nod to the culture, Slaughter introduces a local podcaster who questions the efficacy of the initial investigation. This, in turn, gives Emmy’s son, Cole—a recent addition to the North Falls PD—pause. Though loyal to his mother and grandfather, he has no stakes in the initial investigation and brings a fresh, unfettered perspective to the case(s).

The increasingly introspective Gerald is also open to the prospect that they may have gotten it wrong the first time around, Emmy, however, is not—a stubbornness born largely out of the personal fallout from the first investigation. Admitting fallibility would mean admitting that she failed the girls and Hannah (not to mention herself) … again.

“She’s so affected [by what happened to them] … and the whole Hannah of it all, the fact that she lost the most meaningful relationship of her life because of this case,” Slaughter says. “She’s feeling the sting of the mistake she made, which in the context of mistakes is such a small one—not listening to Madison—but it just happened to be at the most critical time.”

The sheriff, who harbors his own regrets over his handling of the investigation, insists that the FBI be brought in. Representatives from Atlanta’s Field Office soon descend on North Falls, as does Jude Archer, a recently retired agent with a vested if veiled interest in the crimes and community.

“She has a very different experience being in the FBI,” Slaughter says of Jude’s wider worldview, which stands in stark contrast to Gerald’s “Mayberry kind of existence” and Emmy’s “smaller town mindset.”

Jude’s, then, is an understanding on par with Cole’s generational awareness, that “everybody has an invitation in their pocket via their phone for bad things.”

While age, experience, and jurisdiction divide these four generations of crime solvers, they are not without common ground—or shared history.

“You know, there’s a lot of secrets in this book,” Slaughter teases, noting that the county at large—made up of different economic and industrial areas, and different factions of the founding family—is rife for such things.

“You have the good Cliftons and the bad Cliftons and the rich Cliftons and the poor Cliftons, and you have them involved in the seats of government and in policing and all these other things,” she says. “So I was really able to build this world in a way where you have all these avenues for stories and all these secrets that I can tell about the characters as the series goes on.”

Accordingly, Slaughter is already looking several entries ahead, even as the first is only just now hitting shelves. But long-time readers needn’t worry that she’s forgotten her roots. She’ll also continue to pen the Will Trent series (which serves as the inspiration for ABC’s hit drama) and occasional standalones.

“One of the greatest pleasures of having written so many books is that I have the patience to plant these seeds,” she acknowledges. “I’ll keep doing it as long as they let me keep doing it.”

***