In 2014, two 12-year-old girls lured their friend into the Wisconsin woods and stabbed her 19 times, as a tribute to the fictional entity Slender Man. The case captured the public’s imagination and sparked a debate about the effect of the internet on young minds—one that it feels we have yet to resolve.

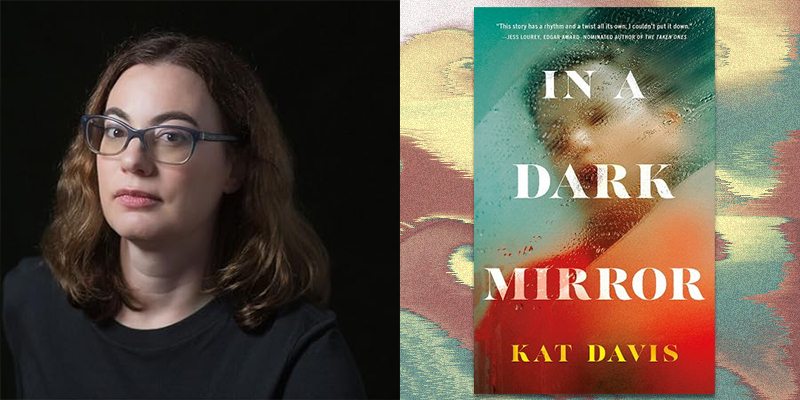

Kat Davis’s tender, lyrical debut, In a Dark Mirror, is told in two braided timelines that explore a similar (though fictional) crime and its wide-ranging repercussions. The first storyline mixes the palpable horror of “Him” with the everyday horror of adolescence and imagines the days leading up to a brutal attack. The second storyline focuses on the return of one of the original perpetrators from a years’ long sentence. Now an adult, she has to reckon with thorny questions of morality and redemption. Can she come back from the evil she committed in childhood? Can anyone?

Given that my recent debut, Rabbit Hole, also focused on the lure of anonymous message boards and the double-edged sword of our national obsession with true crime, I was eager to sit down with Davis and ask her some questions. Over the course of our conversation, we discussed obsessive friendships, fairy tales, and how Davis approached translating headlines into multidimensional characters.

KB: The inspiration for the book is the 2014 Slender Man stabbing that happened in Wisconsin. What is your relationship with that real crime and when did it occur to you to transform those events into the germ of this novel?

KD: I wrote a couple of failed novels before this one. I had been working on a novel about high school girls that had a creepy element to it. It had potential for the first fifty pages, but after that it lost momentum. I kept writing and rewriting it, but it was going nowhere. I’d previously read about the Slenderman stabbings, and it came into my mind again, so I re-read some of the nonfiction pieces about it. There’s some really good nonfiction writing about that case. And I thought it would make a great novel, but I also thought, it can’t be a novel because the real-life events are already so extreme. It seemed like there would be nothing left to fictionalize in a way. In the days and weeks that followed, I’d be walking around and daydreaming… if I did do it, how would I do it? And one night just before going to sleep, I had this image that I knew would be the final image of the novel. That was when I decided to try to write it. At that point, I had a direction and questions that only fiction could answer. I wanted to try to understand what was happening in the characters’ heads—that was the really interesting part to me. And how would you understand as a grown-up this awful thing you did as a 12-year-old kid? So, I kind of always knew there was going to be this other, later-in-life timeline as well.

KB: The central question of that later timeline, I felt, was can you come back from an act of violence? Maddie is wrestling with questions like “Am I evil?” Her self-knowledge is so shaky, because of the way the crime defined her youth.

The “failed novels” that preceded In a Dark Mirror—were they also crime fiction?

KD: They were literary fiction with female protagonists. The first one was the meandering story of someone’s life. It really had no shape to it.

KB: I have one of those.

KD: For me, there was a kind of staircase of learning how to write a novel. The second one—I had a good premise, but didn’t know what to do with it. I didn’t see myself writing a crime novel. But there’s something compelling about the structure, the built-in high stakes, the tension that arises, the mystery. All of those things. For a first-time novelist, still trying to figure out how to write a novel, it’s helpful.

KB: Since we’re talking a little bit about form… do you know Kate Bernheimer’s work, “Fairy Tale is Form?”

KD: Yes.

KB: I was thinking of her notion of “normalized magic” and how it is a feature of both childhood and of fairy tales. Your book is concerned with this adolescent period where the magic of childhood is fading, and the girls are involved in the desperate, joint creation of this last, spooky fairy tale. You have an epigraph from “Little Red Riding Hood,” so I was wondering what you feel the book’s relationship with that genre might be?

KD: The nursery rhyme epigraph (“Sugar and spice,/And all that’s nice;/That’s what little girls are made of”) came into my head as I was working on the first draft. It seemed creepy, and it fit in an ironic way to undermine the notion of girls being nice all the time. If you’ve ever been a girl, you know that the cruelest people around you and the most norm-enforcing are the other girls. The fairy tale question is interesting. I encountered Kate Bernheimer’s work in graduate school, so I think I probably did have some of that in the back of my mind. Originally “Little Red Riding Hood” entered the story in one of Sage’s sections, and I kept coming back to that image of Sage as Little Red Riding Hood. I hadn’t thought about that story much since childhood, but as an adult I asked myself, what is the wolf? The wolf is men and sex and all of these things that are scary to a young girl. That particular fairy tale felt resonant and appropriate for this book.

KB: Did you find yourself revisiting that period of your own life?

KD: I revisited my childhood and used it to re-set the book. I set it in a fictionalized version of where I grew up, so that I could use those memories. The scene where Maddie goes to the pool for the first time and doesn’t realize that she looks awful because she’s wearing a suit that is too small and she’s busting out of it—that happened to me when I was 12 or 13. All of sudden, these guys were looking at me, and I couldn’t figure out why or what it meant. Apparently, that was some sort of foundational adolescent trauma.

KB: There was this girl in my fifth-grade class who pulled me aside at one point and said “you need to start wearing a bra.” And I think about that probably once a month, the shame of that, that she knew and I didn’t know. It had snuck up on me.

Since you mention re-setting. The current setting, in Maryland, feels like a far cry from the real crime’s setting in Wisconsin. It also had this American Beauty, Blue Velvet “everytown” feel. The suburban ennui is so palpable. How do you feel the setting drives the story?

KD: I did rewatch Blue Velvet while I was writing this. That image where the camera dives below the well-manicured lawn and everything is alive and squirming and dark—I did have that idea in my head. It also reflects where I grew up. I had one of those 90s childhoods in the suburbs where you just can’t wait to get out. The suburbs are an American invention, but maybe not one of our better ones. You live in these big houses far apart from other people. At a certain age, there’s basically nowhere to go and nothing to do, right when you want to be going places and doing things. You don’t have a car, you can’t drive. You’re stuck. In the novel, the suburban setting feeds into the idea that the world of these girls is so insular. They really have no idea how good they have it, so they wreck their lives for basically no reason—because they’re bored.

KB: And that restlessness will drive you to the internet if it’s available, right? The early timeline here is 2007, but in the later timeline, Maddie comes home and she’s once again stuck in this house. Now, she’s not even going to bike to a friend’s house, because she doesn’t have any friends. Where is she going to go except into her computer?

How was writing the internet part of the book, recreating message boards and AIM conversations?

KD: I put that part off a little bit, because I needed to create characters that would repeat with the same usernames. You would know from writing Rabbit Hole. But when I got around to it, I had fun, because for the first time I had control over the discourse on the internet, which can be so crazy. I hesitated with that storyline, thinking, no one’s going to buy that there are people who actually believe in this sort of boogeyman. But then I read stuff on the actual internet and I thought, no, there are probably a small number of people who might realistically get into this.

KB: When I was writing Rabbit Hole, I felt I had to actually tone things down in the book, because on the page, it read so over-the-top, even though it was how people really talked on internet message boards. There’s nothing that you can’t find online, but there is something different when you’re inventing it.

How did you come to the structure of the book with these dual timelines that are woven together? You have the 2007 timeline when the girls are in the lead-up to committing this crime, and the 2017 timeline, which I assume you invented from whole cloth.

KD: I did invent it from whole cloth. Although I heard recently that the girl who is the basis for Maddie’s character had been released. I’ve avoided reading the articles because what if I inadvertently wrote something that came to pass? It felt like life imitating fiction in that weird way.

I think I knew early on that there would be these two timelines, or at least an extended flashback. As I wrote it evolved into less flashback and became more clearly two narratives braided together.

The idea that it was going to move through all three girls’ perspectives was also there from the beginning. Because I knew I wanted to know what Maddie was thinking, at least in the earlier timeline, and what Lana was thinking and experiencing in the early timeline. And I didn’t like the idea that I would just represent the perpetrators of this crime and not the victim.

But it was hard to find an arc for Sage, the victim. The first few scenes I wrote, she was just hanging out, but she needed to be on her own quest, which gets interrupted by the stabbing. And three people, a trio, is always an unstable formation. There’s always that possibility that two are going to gang up against one. I thought it would make sense to move through their minds to try to get a larger picture of what happened.

KB: Was it challenging to write Lana’s sections since she’s gradually losing her grip on reality? How did you approach writing mental illness?

KD: For whatever reason, Lana was the character that came to me first. I knew what point I was writing her towards, and unfortunately her path was one of disintegration, basically. I read a little bit about schizophrenia, but mostly, I just read about the original case and what the experts there thought was going on. My main thing was, I didn’t want to be exploiting mental illness… I wanted to show that she’s a person, and that what was happening to her was also a tragedy because she was actually losing her mind. It must be terrifying seeing things that aren’t there as a 12-year-old—a scary boogeyman telling you to kill your friend. But she’s also morally simpler than Maddie, because Maddie doesn’t have that excuse. Maddie makes a choice to go along with this crime.

KB: Maddie is less afraid to commit murder, less afraid of this imaginary demon, less afraid of leaving behind her whole life and her family, than she is of losing her friendship with Lana. That rang so true to female friendships at that age. What is it about those relationships that create that kind of pull?

KD: I remember that sort of possessive feeling of “she’s my best friend.” When you look back on that, as an adult, it’s kind of creepy, the influence that you have over each other.

KB: There’s something sort of sad about it, too. You don’t realize until that period is over that your friendships won’t always feel like that. You’ll never make a friend in adulthood like that.

Have you thought about what might happen if anyone involved with the actual case picks up the book? Has that occurred to you?

KD: Yes. It’s a very recent crime, and the girls were very young. Writing the book felt a little transgressive. I hope the girls and their families don’t go near the book. I think they have all been through enough. But if they were to read it, I would hope that they would see that I tried to humanize these characters. I ended up empathizing with all three of these girls in these very different positions.

KB: As I was reading it, I couldn’t remember if the real life victim lived or died. But then I figured maybe that didn’t matter, because you’d be doing a Tarantino thing, an alternate ending.

KD: That was a question when I started writing. Sage was Schrodinger’s cat. Is she alive or dead at the end? And I thought, it’s my book, I can do whatever I want.

KB: Are there books that you feel are in conversation with In a Dark Mirror?

KD: The one I had in mind while I was writing was Emma Cline’s The Girls, because she takes the Manson murders and adds a character and fictionalizes them. I thought I would do something similar, but the actual crime would be in my book in a way that it wasn’t in that novel. I probably had some Megan Abbott novels kicking around in my head as well, in terms of writing about adolescent girls in books for adults.

KB: Do you read a lot of crime fiction?

KD: Not until recently. As a reader, I’ve generally been into literary fiction. I’m drawn to long autofiction novels where women think a lot about their lives and nothing happens. But my husband and I usually watch a little TV at the end of the day before bed. And often it’s true crime or a crime thriller.

KB: What is the appeal of true crime for you?

KD: I think it’s probably the same things that draw a lot of readers to crime fiction. There’s a mystery of some kind. You know something bad happens, but you want to know how it happened. Also, violent crime is an intense human experience. It’s a chance to ask: what is the nature of evil? Why do people who are normal enough sometimes do awful things? That’s more interesting to me than why does the serial killer kill? Because we can just say: this person is a psychopath, he’s evil. It lets the character off the hook in a way.

KB: Are you working on another novel?

KD: I’m in the early stages of working on a novel that is very different than this book, although the more I work on it, the more similarities I see. The question that you mentioned earlier, about whether a person can come back from an act of violence, I find that very compelling.

***

Kat Davis’ debut suspense novel, In a Dark Mirror, is now available from Thomas & Mercer.

Kate Brody’s debut suspense novel, Rabbit Hole, is now available from Soho Crime.