Before I’d ever heard of crime fiction, or thrillers, or psychological suspense, I knew about detective stories. As a child, I’d sneak out of bed to swatch the opening to the PBS series Mystery!, with its iconic Edward Gorey sequence of gloomy houses and damsels in distress. Sometimes I’d manage to stick around for part of the show before my parents sent me back to bed, but the episodes themselves often struck me as slow, full of shots of dark streets and men having serious conversations while holding umbrellas.

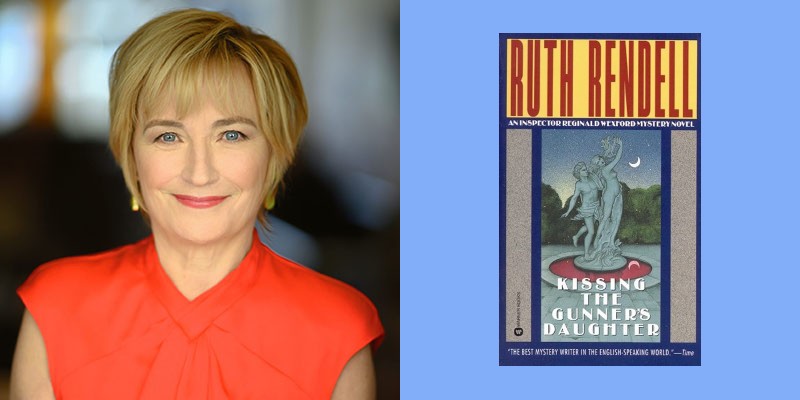

Fortunately, my tastes have changed since then. Though the adaptations of Ruth Rendell’s Inspector Wexford series never aired on Mystery!, the novels traffic in all the conventions that failed to grab me back then: lots of talking, lots of weather, and an elderly detective who often seems to need an umbrella. In the fifteenth novel in the series, Kissing the Gunner’s Daughter, Wexford investigates the murder of Davina Flory, a pioneering sociologist, and her husband and daughter. Reading it as an adult, I loved Wexford’s dry wit, the way Rendell punctuates the even tone with incidents of startling violence, and most of all the prose, which moves effortlessly between descriptions of the fairytale forest in which the victims live and the horror-movie desecration of the crime scene.

When I first approached Kate White for an interview for this series, I assumed she would pick a psychological thriller like those for which she’s best known. After beginning her career in journalism and serving as the editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan, she’s written seventeen novels, including eight in the Bailey Wiggins series and nine standalones. Her books are so fun to read that she makes it look easy, even as her productivity and consistency make it clear that writing on this level is anything but. I once read White’s novel The Fiancée in a single sitting while stuck on a layover, and I’m eagerly awaiting Between Two Strangers, out this May from Harper. I was thrilled to speak with her about what Rendell has to offer the writer and reader of crime fiction across subgenres.

First, I want to thank you for turning me on to Ruth Rendell and Kissing the Gunner’s Daughter. I’d never read any of the Inspector Wexford series before, and I just devoured this one. Had you read all of them? What was it about this one in particular that stuck with you over the years?

I just found it hypnotic. There’s something about a good police procedural that takes you along, like you’re floating on a river. This is the fifteenth in the series, and I read them in order. I liked the fact that unlike PD James, Rendell never cheated the reader. She never pulled the rabbit out of the hat unexpectedly without having left clues. I liked her red herrings, and I appreciated her skill with the series as a whole, but this one really grabbed me, and I think there were two reasons. One, that the murder scene is just so gruesome, and chilling, and extravagant, and it just hooked me. Then the shock of who the killer is, and the way the revelations at the end unfolded, were just so organic, that you came to understand that the novel was really character-driven, based on greed and passion.

Today the market is so flooded with psychological thrillers that the stakes have to be higher to grab people’s attention, but I feel like I’m reading some stuff now that’s just so over the top. It’s like Jaws VII or whatever, where the shark comes out of the water and takes down the helicopter. There was a book I just read, where it wasn’t just one serial killer, this poor woman had two serial killers chasing her! It’s just too much. And what I love about this book is that Inspector Wexford fails see the truth, in part, because he’s blinded by his own feelings.

That’s such a good point. I don’t want to give any spoilers, but the ending really comes down to human psychology, and to the murderer’s feeling that they need to escape from a situation they find intolerable.

Exactly. It’s one person’s decision—not coincidence after coincidence, twist after twist. The victim doesn’t have a couple of serial killers after her. I love books that end like that, and I think that’s why I like Jane Harper so much. When you get to the end of her books, the conclusion makes sense because it’s character-driven. It’s how life could be under certain conditions.

We must have the same tastes. I was reading Exiles and put it aside to prepare for this interview, and The Last Man is one of my favorite novels.

She’s so good. I just wish I got to read more books like that. More and more, I feel like I’m trying with my books to come back to character. I always plot out at least very roughly where the book is going, who the killer is and why they did it, but then I come back to trying to let the characters be organic in their choices and let the twist seem to happen naturally. I don’t know if I’m always successful at it, but that’s my goal, and I think this book is just sort of a gold standard for me.

I totally agree with you. The best thrillers are where the twists happen out of the decisions people make rather than them being imposed from a plot level.

That makes me think of another book that I love: The Killer Next Door, by Alex Marwood. It’s just incredibly wonderful psychological suspense that also feels very organic. The characters make choices based on their own needs and desires and instincts, and that then drives everything, including the wonderful revelations and twists that happen.

I’ll put that on my list! Can you tell me about your first exposure to the suspense or mystery genre?

For me, as for a lot of women, my love of suspense fiction started with Nancy Drew. Then when I was a little older, I saw a list in Esquire of the best murder mysteries of all time. And I realized, oh my gosh, there are grown-up murder mysteries out there! Agatha Christie was on there, and Josephine Tey and Raymond Chandler. It was only really much later that I started reading things that would be characterized more as psychological suspense, and then of course Gone Girl just exploded. Now there’s so much of it out there. And I think one thing about Jane Harper’s books is that they’re police procedural, but they’re also kind of psychological suspense in the sense that the detective has to deal with the personalities and characters of the people he’s investigating, as well as his own flaws and limitations.

Do you remember when you first read Kissing the Gunner’s Daughter, or in what circumstances?

I don’t. I can’t tell you exactly where I was, but I was probably drinking some English breakfast tea or some Bordeaux, and I was in a very comfortable chair.

That sounds lovely. One of the things that really stood out to me was the first scene, when Detective Sergeant Caleb Martin confiscates a toy gun he finds in his teenage son’s school bag. Later that same day, Martin finds himself in line at a bank during a robbery and pulls out his son’s fake gun to try to stop the robbery, with disastrous results. It creates so much tension for the reader to see him with this gun in his hand that we know isn’t functioning, and I was wondering if you had any thoughts on that opening.

I had actually forgotten about that until I reread it, but I do appreciate that scene. In some ways, it’s a little bit of a sleight of hand, because she immediately tells the reader that Martin really isn’t that important to the story as it’s going to unfold. On the second page, she switches to an omniscient narrator and tells us, “This was the first link in a chain of events that was to lead to six deaths. If Martin had found the gun before he and Kevin had left the house, none of it would have happened.” To take on that omniscient point of view all of a sudden, so we’re not just in Martin’s head, it’s like she’s saying, “Don’t get too attached to this storyline.” It’s just brilliant.

You’ve mentioned the murder scene, when Wexford and his colleagues arrive at Tancred House to find that Davina Flory, her husband, and her daughter have been killed, and her granddaughter has been seriously wounded. What stood out to you there?

I can’t think of a murder scene that gripped me as much as that one. There’s blood on the walls, blood dyeing the tablecloth, and the grandmother’s head has fallen into her plate. It sounds almost Shakespearean, and at the same time it’s just so gory and over the top, and it’s especially startling because we’re in this fussy little British town where nothing much happens. It’s just like, wow, it comes out of no place.

I loved that scene too, and I thought part of what made it work was the setting. The description of the country house where much of the novel takes place feels like something out of a Victorian novel, but some readers might find Rendell’s pacing unnecessarily slow or ponderous in places. What do you think?

It seems like way too much description if you compare it to books today, where there may be no description other than the building is white, or what the person is wearing. You’re dealing now with a marketplace that has a shorter attention span and is used to things moving very, very quickly. In this novel, though, there’s a strong connection between setting and character. The fact that the family lives in this secluded area, in these woods they own, and in this beautiful house, really hints at who they are—they don’t have friends, they’re very isolated. The grandmother is weird, and her marriage to her much younger husband is weird. I think there’s something to be learned by someone who writes about setting so incredibly well, but probably with what readers are like today, you’re not going to get away with that ornate kind of description and keep them with you. I know people say write a book you want to write, but I always say that if you also want to sell books, you have to kind of balance those things.

What have you learned from the novel that you’ve applied to your own work?

I think the lesson for me is organic, organic, organic. Of course I love the moment when I have a great idea for a twist that sometimes seems to come out of my head full-blown, but I always want to come back to character and let all the twists come from that, so they feel real and authentic.