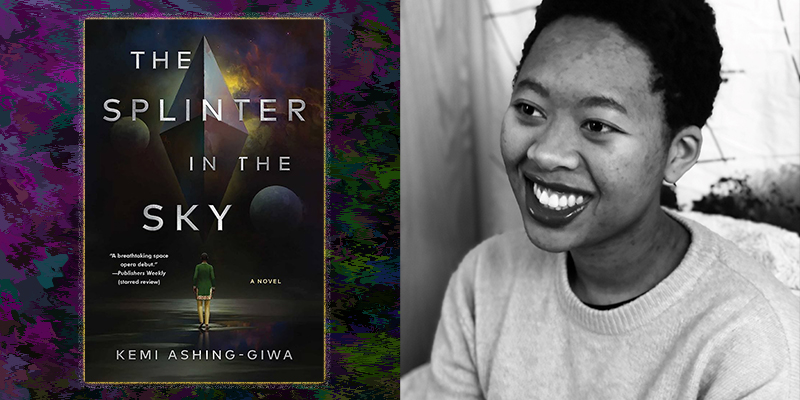

Molly Odintz: What did you want to explore in your novel about the experience of occupation?

Kemi Ashing-Giwa: The aspect of occupation I most wanted to explore was the contradictory nature of the imperialistic machine. Across history, the most “successful” empires grew in no small part via assimilation. (How we determine the metrics by which the success of nations is measured is a complicated question well worth delving into, but that’s for another time, and for those more knowledgeable than I). These empires not only forced their own way of life upon peoples they viewed as “lesser”—they also absorbed and sometimes even adopted the cultures of the defeated. Empires are hungry creatures; they survive only by devouring others. True occupation merely begins with land.

In The Splinter in the Sky, even as the Holy Vaalbaran Empire crushes Koriko beneath its boot, it steals Korikese artifacts for its most prestigious institutions to study, mimics Korikese customs, and appropriates Korikese dress. It goes without saying that these practices were drawn from reality.

I am from a family of multigenerational immigrants; my mother is from Trinidad, her mother is from Grenada, her father is from China, and my father is from Nigeria. All of these countries suffered (and, in many ways, continue to suffer) at the hands of colonialism and imperialism; my parents were both alive when their homelands declared independence from British rule. Exploring that ongoing history, along with the strength and ingenuity it took (and takes) to fight oppression, was a way for me to explore my own family’s history.

MO: What makes genre fiction so good as a medium for exploring social issues?

KAG: The speculative aspect of science fiction (and fantasy) constructs a sort of distance between real world issues and the issues the genre tackles. For me, at least, this distance offers a sense of safety, as well as flexibility—one can explore the human condition and critique society without the necessary constraints of historical or contemporary fiction. Science fiction can also present extremes to really drive a point home; dystopian and utopian fiction are incredibly powerful—and popular—subgenres.

MO: What are some of your influences?

KAG: They change from project to project, since I try to challenge myself and write something new with every story. That being said, N.K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season was, by far, my biggest influence for The Splinter in the Sky. If it hadn’t convinced me there could be a place for my stories on shelves, I doubt I would’ve ever pursued publishing. Other significant influences for my debut novel include Rivers Solomon’s An Unkindness of Ghosts, Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch series, Arkady Martine’s A Memory Called Empire, and Nghi Vo’s The Empress of Salt and Fortune.

MO: How did you balance between the grand nature of Space Opera and the quiet plotting of intrigue?

KAG: The setting of The Splinter in the Sky spans a solar system, but most of the plot takes place in the shadows. Although the story is technically a Grand Space Opera, the main characters are deeply invested in avoiding Grand Space Opera Events (i.e., interstellar war), and work to do so via relatively subtle (but often nevertheless bloody) methods. I can’t say much more without spoilers!

MO: Who are some writers you want to recommend to our audience ?

KAG: I wholeheartedly recommend reading any of the stories I mentioned earlier. One upcoming book I’d suggest keeping an eye out for is Hana Lee’s Road to Ruin, a high-octane science fantasy tale that’s pretty much a sapphic Mad Max: Fury Road with magic. It comes out in 2024, and though I’m only a few chapters in, I can assure you that it involves a whole lot of delicious intrigue.

MO: What does genre fiction provide when it comes to telling queer stories?

KAG: Genre fiction has the ability not to only explore or critique societal ills but also to illustrate how ridiculous bigotry is. Many works of science fiction and fantasy take prevalent contemporary biases for granted, despite the fact that those stories often take place a thousand years in the future or in another universe entirely. This can inadvertently suggest that such prejudice is only natural.

Not every setting has to have the same problems ours does—after all, not every society in real human history has had the same problems we do. One can, for example, build a diverse, queernorm world and still criticize homophobia (or any other -phobia or -ism) through metaphor. There is, of course, a difference between unexamined bigotry and an analysis of that bigotry. Stories that explicitly deconstruct and condemn intolerance are important and necessary, but I don’t think there will ever be enough stories of unabashed, uncomplicated queer joy too.

***