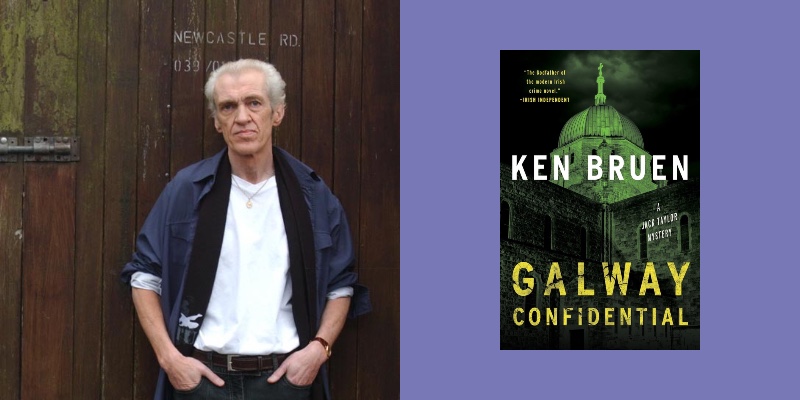

Over the course of seventeen Jack Taylor novels, Ken Bruen’s most celebrated creation has endured the following (small sample size, too): extreme hangovers, numerous beatings, the deaths of close friends, and those not so close, numerous children, including his own, and myriad other injuries and humiliations. He’s also “dispatched” more evil individuals than any crime fighter could fathom.

When we meet Jack in Galway Confidential, he’s been in a coma for nearly two years and still has a way to go to recover from the vicious stabbing that nearly ended his life. There’s also a strange man named Raftery at his side, who’s been hanging around Jack’s hospital room, and claims to the staff that he’s Jack’s brother. Jack finally has the wherewithal to, uh, inquire, who are you? Raftery tells Jack that he saw him being stabbed and rescued him from certain death. That’s good enough for Jack and, his savior becomes a new close companion.

Soon, Jack is out of the hospital and taking on anther string of crimes. Nuns are being brutally attacked in Galway, and Sheila Winston, a former nun who was close with a dear friend of Jack’s, Sister Maeve, who was killed in Galway Girl, comes to Jack and asks him to help find who is behind them. “Go to the Guards,” Jack tells her. “I’ve been,” she replies, “but they are nigh overwhelmed with the demonstrations against the lockdowns and, too, assaults from the anti-vaxxers.” So, Jack, still not fully recovered, agrees to see what he can find out.

Set in the immediate aftermath of the worst of the pandemic, Galway Confidential explores in detail (as do the other books in the series) the unique complexity of Irish society, with its deeply infused blend of the Church, a roller-coaster economy and a propensity for violence, particularly involving knives…and in these stories, those knives aren’t just sharp, they’re serrated, too.

There’s another “Jack” who also resides in the loner, action realm: Lee Child’s iconic Jack Reacher. On the surface, these two one-man purveyors of essentially vigilante justice would seem quite similar.

I asked Bruen, over email, aren’t they basically the same character? After all, each one has a moral code that compels them to take on injustice, albeit, Reacher being more of a quintessential loner compared Taylor, who has a rather more collaborative approach.

Says Bruen, “For starters, Reacher is pretty much a hero, Taylor not so much. Reacher doesn’t read, Taylor does and voraciously. Reacher has an astounding success rate with women and Taylor is a complete disaster.”

It’s also true that Reacher doesn’t suffer injury to the extent that Taylor does. In fact, Taylor is a regular Christ figure, who has numerous resurrections from his extensive physical traumas. Why so much pain? So many injuries? “Regarding Taylor’s injuries, I want to explore how much punishment a body can take.”

And the level of violence Taylor faces in Galway? “The series has become more violent as the city around me becomes so.

Knife attacks are a daily occurrence and the clergy have been targeted on many streets.”

The Taylor series feels particularly moored to Bruen’s own personality. There’s a distinct sense of a symbiotic approach to life between the two. Or is this reader just projecting? “My own love of books and a short temper helped form the character of Taylor,” responds Bruen. “Jack was brought up in dire poverty, this is a base of his seething anger.

I based Jack on my brother who died a homeless alcoholic in the Australian outback. I wanted to write about the Irish obsession with drink and the terrible outcome. Books, like myself are and have been the salvation of Jack.”

Several thematic affectations ebb and flow through the series. Jack Taylor may be a coke-snorting “J” (Jameson) whiskey drinker and an overall self-abuser, but the man is literate as hell. The Taylor novels are rich with poetry, crime fiction, musical references and philosophical musings.

Bruen, who has a PhD in Metaphysics is as noted above, a voracious reader (and lover of music as well). He repeatedly alludes to several literary figures, notably among them the poet and Jesuit priest Gerard Manley Hopkins. “I am fascinated by Gerard Manley Hopkins, and that The Wreck of The Deutschland had the drowning of all those nuns. Nuns are a prominent feature of Jack’s life, mostly against his will.”

From The Wreck of The Deutschland:

Sister, a sister calling

A master, her master and mine!—

And the inboard seas run swirling and hawling;

The rash smart sloggering brine

Blinds her; but she that weather sees one thing, one;

Article continues after advertisementHas one fetch in her: she rears herself to divine

Ears, and the call of the tall nun

To the men in the tops and the tackle rode over the storm’s brawling

Another reoccurring theme in Jack’s life are the “sidekick” sub-protagonists who enter his orbit. These men serve as dark to Jack’s light. In Galway Confidential, it’s the strangely ubiquitous Raftery. It reveals little to say that their relationship does not end well.

Bruen notes, “It has been my experience that instant friendships should carry a health warning.

Jack takes people at face value and lives to regret it. It has been said that alcoholics continually make new friends as they blow through so many.

Jack has the neon sign over his head that says, ‘Dodgy folk assemble here’. Jack works on the basis of ‘Keep your enemies close but your friends closer’

The many betrayals he endures is part of his genetic makeup, [and] the history of Ireland is littered with betrayal.

Jack doesn’t probe new friendships too closely but relies on the notion,

‘This is a good drinking buddy’,

Known here as ‘The Guinness theory.’

Much like most of Galway folklore, it is based on

‘Will you come for a pint. ‘That’s the best I can explain it.”

And what about the “mother issues” we see in many Irish stories? Frequently they are bitter, repressed and lacking emotional empathy. Or so it seems. In one scene, Jack and Raftery are having a cup of coffee, and Raftery “…slurps his coffee, few sounds as irritating; he caught the look on my face.

What’s eating you, bro?

Bro!

I sighed. I come from a long line of sighers. My mother, the bad bitch, could have sighed for Ireland. Irish men are supposed to love their mammies.

Phew-oh.

Not me, not ever. She was the walking shape of pure malignancy, and pious to boot.”

Bruen acknowledges, “For a long time, Irish mothers were of the Quiet Man variety, sweet and funny. I wanted the opposite. Religion ground them down. The church no longer has this power.”

Yet if Jack is tethered to anything, it’s that Church, those nuns. As he investigates, the murders and beatings of nuns, he meets with the “boss,” the Mother Superior, but more importantly, another encounter late in the story with Sheila Winston: Jack tells her he’s figured out who is behind the current spate of killings.

She says, “There’s one thing to do now.” Jack thinks, “I was about to lay out about how going to the Guards was a waste of time without evidence, but before I could start my lame litany, she said, ‘You are going to kill him.’

“Nuns are a prominent feature of Jack’s life,” Bruen says. “Mostly against his will. With the Mother Superior, I wanted to paint a colourful feisty woman who is determined to save Jack and to show how much in the human condition nuns are, to break through the almost fearful mystique in which they are seen.”

Although a far cry from the previous century, the Church still pulls, perhaps just with more subtlety.

And then there was Covid. It’s been over three and a half years since the previous Jack Taylor, Galway Girl. As with most of the planet, the pandemic walloped Ireland and, not just a little. Ken Bruen:

“Covid hit hard. I had health problems of a different kind and was knocked out for about two years, I wanted to explore this new landscape of separation, masks, panic, fear, dread. A new kind of isolation emerged and even after Covid, many people had a fear of venturing out.

For the first time in forty years, I didn’t have a book published. That was an alien landscape. I’m still maneuvering.”

During this period, Bruen actually did publish a novel, Callous, a standalone (with the occasional reference to old Jack). Callous is a play on words for the name of a woman named Kate Mitchell, a mostly recovering junkie who inherits her aunt’s seaside cottage. What she doesn’t know is that her aunt was murdered by a member of a Zeta gang headed by crazed dealer named Diogenes Ortiz, or Dio, for short, who with his enforcer, Keegan, are “procuring” houses near a body of water for meth labs. A little murder is sometimes necessary to procure said houses and Kate’s aunt had to go.

Keegan, “… had a total, almost psychotic, devotion to his boss. Dio had rescued him from a hellhole of a prison cell in Nogales.” Unfortunately for Kate, she looks like the wrong person. “[His] only concern regarding Dio was the lunatic fixation Dio had for Maria Callas, and now Kate Mitchell. Something in the whole scenario spoke to him of weakness.”

Callous is typically brutal and gory, but several so Bruen touches make the story funny at times. When one of Kate’s troubled brothers who have come to help her ward off the Zeta boys, is shot nearly point blank and thought to be dead, he ends up in the ICU instead. What saved his life? In his jacket was a copy of…the Bible. The poet Hopkins has a cameo reference and a particularly vicious death occurs when a Rosary is used to stab an eye of one of the numerous victims in the story.

Bruen merely states, “I wrote Callous as a short blunt shot between Jack Taylor books.”

Where do Bruen’s (wonderful) barrage of literary quotes, song references, and so forth come from? He recalls seeing the American roots singer-songwriter Iris Dement, who “…did a gig in Galway and I was among the handful of people there, she gave a haunting rendition of ‘No Time to Cry’

I have as my mantra, her line

‘Bite down and swallow hard.’

It is when I am writing a particular piece and bingo, one of those quotes leaps in my mind and I want to share that.”

And the PhD. in Metaphysics?

“I studied Metaphysics for the most basic reason of all,

I wanted to know,

And to know what?

That is still part of a longing I experience when I stand by the ocean.”

To interview Ken Bruen is an utter delight. Besides providing thoughtful, revealing responses to one’s questions, unprompted gems are tossed out along for the ride.

To wit:

“A guy I know only recently discovered I write and said to me in all seriousness,

‘I thought you had no education.’

And

“Few years back, An English professor, friend of mine said,

‘I need to pay my mortgage, I’m going to write one of them books you do’

I offered him a range of authors and he scoffed,

‘I don’t want to read that stuff, I just want to get the novel done’

Months later, I met him and dejected he was, muttered,

‘I keep lapsing into literature’

I pray daily that I don’t ever lapse such.”

What’s a typical day in the life of Ken Bruen?

“I don’t have typical days as some kick in the face usually arrives by first post. I do rise early to get my writing done, then it’s feed the swans, and turn to see what

Galway has to throw.

Always something off kilter…

Evenings, I don’t guzzle Jameson as one critic suggested.

Would I could.

reminds me the English journalist who was horrified to find I was mannerly!

She titled me as ‘A benign thug’

I’ll take that.”

His wife:

“For years, when my wife was asked what kind of books I wrote, she said’

‘Stabbing types’

Succinct.”

The art of theft:

“The National Library of Ireland listed the books most ‘disappeared’ from the shelves and said Ken Bruen was the No. 1 author whose books were gone, nine titles in all.

I finally got a No. 1 spot. The library here says I am the most stolen. There is a metaphor/ message here, I’m fucked if I know what it is.”

Unsurprisingly, numerous Jack Taylor novels have been optioned for TV. (Not that you can see them in the US.) Bruen was happy: “There are 9 Jack Taylor books and I think the casting of Iain Glen was a smart move.”

An additional series based on the 2014 novel, Merrick was written for Swedish TV and retitled 100 Code and is set in NYC. “Sending Noir to Sweden, that is sweet!”

Also two films, one from a standalone, London Boulevard (2001) and one based on a different series, Brant and Roberts (cops) Blitz, (2002 starring Jason Statham.

Bruen, effusively: “London Boulevard, the movie is I think very underrated, Bill Monaghan had a vision of it as a commentary on social celebrity and I think he didn’t get credit for how well the movie worked.

Blitz was great, they really captured the humour and I got to play a priest! Blitz, on DVD was a massive hit. That’s the Jason Statham effect.”

Galway Confidential is, in Bruen’s words, the “penultimate Jack Taylor novel.” Coming next, Galway DNA concludes the series. It’s already written.

So? “I am working on a crime novel that I hope is a huge distance from previous work.

I want it to be hard, fast and funny/

Change of font to emphasize how early I am on that.”

Undoubtedly, it will be all those things, and more. This reader is ready now.

***

For a deep – seriously deep – critical, very academic analysis of Bruen’s work in the context of other contemporary Irish crime writers, see the recently published book, Finders: Justice, Faith, and Identity in Irish Crime Fiction, by Anjili Babbar