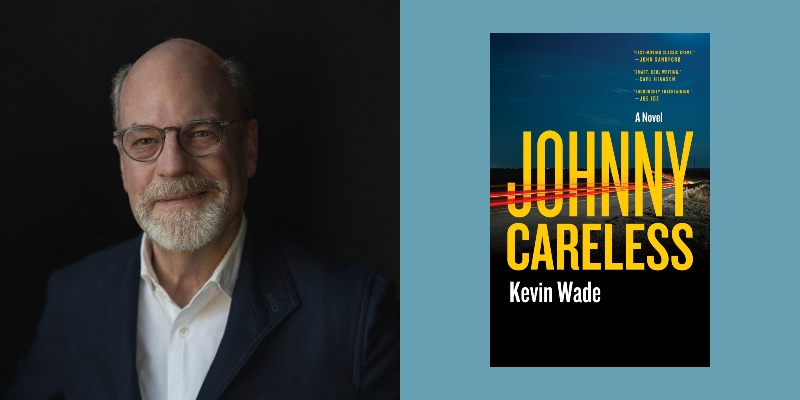

I met Kevin Wade in the 1980, not long after his play “Key Exchange” was produced off-Broadway to rave reviews. This early success led to the 1988 hit “Working Girl,” directed by Mike Nichols, who became a friend and mentor. After a string of notable films such as “Meet Joe Black” (1998), and “Maid in Manhattan” (2002) , he moved to television, joining “Blue Bloods” as a writer in 2010. Since the second season, Wade has been the show’s executive producer and showrunner—which has to be some kind of record in network television. In his debut novel, Jeep Mullane, a former NYPD detective who has returned to his hometown on Long Island’s North Shore to become the local police chief, has his world turned upside down when the body of his childhood friend, Johnny Chambliss, nicknamed “Johnny Careless,” washes up in the waters of “Bayville.” The investigation forces Jeep to confront his past while dealing with his grief for his lost friend. Simultaneously, he must handle corrupt businessmen and crack an auto theft ring plaguing the area, adding pressure to his new job.

Q: How did your background in screenwriting translate into the novel? Asked another way, how would Jeep fit in on “Blue Bloods”? He’s a former NYPD detective after all.

WADE: Well, my background in screenwriting is also a background in storytelling I guess so I had some tools there. But it was a huge adjustment going from dialogue and actor-driven dramatization to executing every last detail yourself; moving from a wholly collaborative form to a solo one was a really challenging course.

WADE: Well, my background in screenwriting is also a background in storytelling I guess so I had some tools there. But it was a huge adjustment going from dialogue and actor-driven dramatization to executing every last detail yourself; moving from a wholly collaborative form to a solo one was a really challenging course.

Q: When did you start reading crime fiction? Who are your favorite characters in the genre? I started with my dad’s bookshelf and its row of Ian Fleming, Joseph Wambaugh and Dorothy L. Sayers, which introduced me to suave spies, cynical cops, and ace detectives respectively. As I “grew up” I climbed out on all of those branches and found these favorites – Philip Marlowe, Travis McGee, Spenser, Bosch, Reacher, an assortment of Lehane’s and Hiassen’s men and women.

WADE: Which one would Jeep prefer to have a drink with? Travis McGee for the self-deprecating self-checks, Spenser for the common touch, Hiaasen for the outrage and the laughs.

Q: The Hard-Boiled Private Eye is a cliché, epitomized by Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe. Jeep doesn’t seem that world-weary. He is, in fact, a very funny (and ironic) guy. I assume that’s on purpose.

WADE: It is on purpose. I wanted Jeep to more reflect the reader (or myself) at our best; just trying to meet the day’s challenges with what you have, as best you can, and with some empathy and some humor.

Q: No surprise considering your background that the dialogue is so sharp. And funny. I get the sense that you enjoy writing it.

WADE: I did. After forty-some years of the very specific and pretty formal demands of play, screen and television writing it was a hoot sometimes to free-range off-road.

Q: Do you ever get stuck? Any tricks?

WADE: I got stuck in the beginning when I realized the sheer amount of words that a novel takes, after years of my written pages being mostly white space with some slug lines and (hopefully) lean dialogue. The trick that appeared one day was seeing that I had all the jobs – director, locations, cinematographer, wardrobe, casting etc etc – that all my previous work had a whole crew of collaborators for. I knew just enough to take a stab at those arts and crafts.

Q: Jeep’s relationship with Johnny is a central focus which you examine through alternating chapters of past and present. What gave you that idea?

WADE: “Backstory” is kind of a sin in “dramatic” writing as it slows down the narrative drive to like 5 mph. I hoped this could be a “character driven” mystery and so thought it might be a helpful way to get the reader invested in the characters.

Q: Critics compare your style to that of Donald Westlake and Robert B. Parker? Who are they missing?

WADE: I learned a lot from reading all of Parker and walking in Spenser’s shoes away from the “action” as well as in its midst. Same for John D. McDonald’s Travis McGee. I’d add Carl Hiaasan as he has an expert and enviable way of making his protagonists nimble and savvy but also, often, ‘a day late and a dollar short.’ Which is the way I feel most of the time, suspect many people do, and so it makes for a kind invitation into the worlds he writes about. “Bad Monkey”, and the terrific adaptation that Bill Lawrence did with Vince Vaughn as That Guy, is an excellent example. The reader (or viewer) feels as if they are in familiar hands and fine company.

Q: Characters like Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins provide insight into the experiences of marginalized communities. Jeep gives us a window into the uncomfortable contrast between the wealthy (and secretive families) of what was Gatsby’s “East Egg,” and a local underworld preying on illegal immigrants. You obviously know what you’re writing about. Do you live in “Bayville” yourself?

WADE: I live mostly in Lattingtown on the North Shore, a couple towns west of Bayville, and have for twenty-plus years. It’s an easy entry here to feeling like you’re some degree of outsider with your nose pressed to the glass and looking at the swell life inside.

Q: I also get the feeling you’re interested in Moral Ambiguity, especially the complexities of right and wrong in a place where lines are often blurred.

WADE: Moral Ambiguity isn’t something I’d know how to actually write but any kind of conflict I can use, internal or external, I try to put right to work.

Q: And you also like decades-old secrets, right?

WADE: Who doesn’t?

Q: Every review calls Johnny Careless a promising debut. Can you say if you have any plans for Jeep?

WADE: I am writing a second installment with cautious hopes that the first one gets read and recommended enough to make a sequel welcome.