For more than a century we’ve been addicted to a particular flavor of murder mystery story. A group of wealthy, upper-class people are gathered together in a country house. There’s a butler, people dress for dinner and talk about fox-hunting or how frightfully vulgar Lady Stuffington’s necklace is. And then someone dies.

It’s a trope as old as the murder mystery itself and we’ve seen it played out many times, from The Hound of the Baskervilles and And Then There Were None to the board game Clue. People have been finding bodies in the library for a very long time.

On the surface, its continued appeal is mystifying. Society has moved on. We don’t have to read about rich, white people any more – there are diverse authors from diverse backgrounds (or at least we’re getting there.) We can read gritty, realistic crime, follow hard-bitten cops with issues as they solve the kind of murder that actually happens in real life. Why should we even care about the untimely death of Lady Stuffington? But we do. When I told friends I was writing a novel about a group of privileged former college friends snowed in with a murderer, the result was instant fascination.

Of course, there’s the obvious cozy appeal. Outlandish murders of titled individuals are much easier to read about than gang-related crime in our home city. And the familiar pattern of the whodunnit, where the solution is all wrapped up in a bow at the end, is comforting to us in these post-pandemic times. But there’s more to it than that.

Back in the golden age of detective fiction – the 1920s and 1930s – murder mysteries were a reflection of a class-ridden society. There was a chasm between the lives of the rich and the poor. But while writers were busy killing off fictitious lords of the manor, the social structures that had lasted for centuries were under threat. Aristocrats were crushed by debt, country houses were falling apart and staff were harder to come by as local lads and lasses tried their luck in the offices, shops and factories of nearby towns.

Added to that, Europe was in upheaval. Kings and Emperors had been toppled, socialism was taking root. In the US and beyond, the Wall Street Crash destroyed what remained of the Gilded Age. We were starting to realise that our ruling classes weren’t all they were cracked up to be.

But while social change was the backdrop to these murder mysteries, it was never the theme. His Lordship was never done in by rebellious under-gardeners waving copies of Das Kapital. It went against whodunnit etiquette. In 1928 the writer SS Van Dyne wrote a list of detective fiction rules including the fact that the culprit should never be a servant. “It is a too easy solution.” he wrote. “The culprit must be a decidedly worthwhile person – one that wouldn’t ordinarily come under suspicion.”

In short, with very few exceptions, the butler never did it. The rich were always responsible for their own demise. And that is a major part of the appeal of these upper class mysteries – the idea that there is often corruption lurking beneath the privileged facade. One by one the reader winkles out the characters’ dark secrets – the debts, the affairs, the jealousy – concealed by elegant attire and fine manners. I’ve never thought of myself as a class warrior but it’s fun to see the secrets of the elite exposed.

Flash forward to the 2020s and the world has changed beyond all recognition. We have air-con. We have TikTok. We have a mature democracy. But we still have a society that is class-ridden, with a vast chasm between rich and poor. We’re also in the throes of some important – and often shouty – conversations about equality, privilege and who we think we are as a society. And in the thick of these discussions Knives Out was released. A thoroughly modern country house mystery, it’s populated by updated upper-class suspects: a beauty guru, a neo-Nazi, various trust fund kids and nepo babies. And there’s even poor, pure-of-heart Marta, the modern-day butler who, in a clever twist, really does think she did it. The movie was an instant international hit.

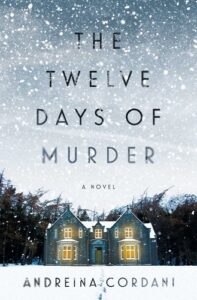

So everything and nothing has changed, and our murder mysteries reflect this. The characters in my book, The Twelve Days of Murder belonged to an elitist murder mystery society in college, which broke up when one of them disappeared. Twelve years on, they’re reunited for one last murder mystery game. Characters include an aristocratic politician, an eccentric trust-funded artist, an influencer, a banker and an oligarch’s daughter. Every one of them has a secret that corrupts them and could bring them down. And, just like those golden age stories of times past, the appeal is in watching how the mighty have fallen.

***