South Korean cinema is a wild, confounding hydra. There is the art house fare winning accolades at international festivals; the steady flow of mainstream, industry-approved movies filling theaters; and the boundless riches of a genre cinema that never ceases to astound. Of course, these types of movies most assuredly overlap as well. South Korean crime films, in particular, are an arsenic-laced delight. Expect investigations proceeding on rainslick streets at night; elaborately choreographed gun duels and all-out brawls with everyday items; and entangled relationships among friends, lovers, and enemies. That’s not all; these tales of crime and woe frequently mutate, becoming something else, mixing their DNA with strands of action, thrillers, police procedurals, comedy, and that staple of Korean cinema: melodrama. By the new millenium, Korean crime films became stranger, bloodier, and more uncontainable, rivaling Hong Kong and Japan for singular genre output. This survey is simply a guide, a sample platter of the delectable works in Korean film history. It shines a spotlight on both landmark films and deepcuts from the 1950s to the ‘00s.

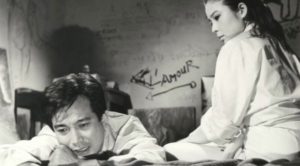

A Flower in Hell (Shin Sang-ok, 1958)

Virtually all of South Korea’s cinema prior to the 1950s is lost due to lack of preservation and the destruction of the Korean War. The late ‘50s, however, marks the revival of the medium, with eight films being made in 1954, to 108 in 1959. Shin Sang-ok—who would later be kidnapped with his wife and actress Choi Eun-hee, forced to make films in North Korea, and finally land in Hollywood and produce the 3 Ninjas movies, of all things, under the name Simon S. Sheen—emerged as one of the few talents from this era. In A Flower in Hell, Shin recounts a doomed romance after the Korean War: When a country bumpkin journeys to the big city looking for his petty thief older brother, a prostitute—the femme fatale of the film—is the wedge between the siblings. This is a simple tale represented in a neo-realist mode with melodrama accents and an end that segues into full-tilt expressionism as the trio stumbles in a fog-enshrouded, mud-drenched field. It’s like the end of Gun Crazy (1950)—or something that F.W. Murnau would’ve dreamed up.

Forever with You (Yu Hyun-mok, 1958)

Known for Aimless Bullet (1961), his downbeat film about ex-soldier brothers trying to live after the Korean War, Yu Hyun-mok made a more crime-inflected picture that undermines the common conception of him as a realist filmmaker. Like A Flower in Hell, this is a fated romance, but one involving a woman and three juvenile delinquents, all of whom lead different lives ten years later: one’s finally getting out of jail; another became a priest; the last, rising to the top of the criminal underworld, is a feared gangster.

Despite the conventional premise and plot machinations, Yu experiments with form. Most of the action, particularly that seen in flashbacks, occurs on massive soundstages, which give Yu the freedom to mount graceful camera movements that swoop, push, and glide around spaces—from interiors to exteriors and back again.

The Housemaid (Kim Ki-young, 1960)

A middle-aged piano teacher hires a housemaid based on a pupil’s recommendation. Yet the maid gradually becomes so possessive that she’ll do anything to remain by her boss’ side in this story of passion gone psychotic.

Along with Shin and Yu, Kim is one of the breakout talents from this period in Korean cinema. His work is extravagent, off-kilter, and psychologically perverse, using this narrative to reflect back on the country’s societal ills. Changing with the times and the problems that they bring, Kim made two more versions of this film: Hwanyeo (1970) and Hwanyeo ’82 (1982). His work endures, going on to inspire Bong Joon-ho and Park Chan-wook’s movies.

The General’s Mustache (Lee Seong-gu, 1968)

Out of all the films listed here, The Ganeral’s Mustache has the least written about. But it’s worth considering as a typical yet effecient genre hybrid effort—the kind that thrives in South Korea. At first, The General’s Mustache is a murder mystery investigation of a dead young journalist, then it morphs into a melodramatic character study of the victim, complete with an animated sequence, black-and-white flashbacks, and flashbacks within flashbacks.

The Last Witness (Lee Doo-yong, 1980)

A detective investigates the brutal murder of a wealthy wine brewer. As the investigator talks with those who knew the slain man, it turns out no one is innocent; everyone is held responsible for the cruelties of society. Government censors—continually hampering directors in this decade—cut a third of this three-hour epic during the time of its initial theatrical relase, most likely due to its fatalistic outlook. Thanks to the Korean Film Archive, it has since been restored to nearly its original runtime.

General’s Son (Im Kwon-taek, 1990)

Set when Japan occupied Korea, Im Kwon-taek’s historical epic is a gutter to gangsterdom tale involving a young beggar who becomes a mafia leader in control of a patch of territory the Yakuza very much wants for its own purposes.

With handheld camerawork from Im’s go-to cinematographer, Il-sung Jung, and lush costume design (everyone’s a snappy dresser with fedoras, three-piece suits, over coats, and coiffed hair), this is a film with an unrelenting pace, seeming never to pause to give the viewer a breather.

Green Fish (Lee Chang-dong, 1997)

Lee’s directorial debut, like General’s Son, charts a young man’s career with the mob. With this genre framework, he explores tiers of loyalty, constraint, and rebellion amongst his characters with a youthful energy conveyed in showy camerawork, incorporating 360-degree traveling shots, POV shots that gradually change, becoming more mobile and detached from a single, human perspective.

Memories of Murder (Bong Joon-ho, 2003)

Bong Joon-ho’s breakout film is also a key one in the Korean New Wave happening at the turn of the millennium. Two investigators—one reliant on instinct, the other on intelligence—take the lead on a string of grisly countryside murders. Tonally, it’s a film that slowly shifts from broad humor to something more lingering and tragic, as the duo spends years on the case. A process-heavy police procedural based on actual unsolved serial killings, featuring haunted detectives, Memories of Murder pre-figures David Fincher’s Zodiac by four years.

Oldboy (Park Chan-wook, 2003)

Oldboy is the film that launched Park Chan-wook’s career, making him—like Bong—an internationally heralded director. The second entry in his so-called Vengeance trilogy, it’s a stylized, ultraviolent film based off a manga. Min-sik Choi plays the lead, a middle-aged businessman prone to drunken sprees on the town, until one night he’s kidnapped and held prisoner for 15 years—and then he’s inexplicably released one day by his captors. The hunt is on to find and destroy the people who locked him up for so long.

A knotty neo-noir, Oldboy demonstrates Park’s penchant for shocking plot turns (they become even more intricate in 2016’s The Handmaiden). And, after ten-plus years, the single-take extended fight sequence, featuring a hammer and many thugs in a narrow hall, still astounds.

A Bittersweet Life (Kim Jee-woon, 2005)

An enforcer falls on the sword when he fails the one job that his boss orders him to do: tail his young girlfriend and see that she isn’t sleeping with anyone else. The boss sics his gunsels on him. A Bittersweet Life is a flashy film, mushy on philosophical musings offered by the protagonist but making liberal use of blood and gore when Kim orchestrates set pieces spotlighting gunfights.

The Chaser (Na Hong-jin, 2008)

A harried detective-turned-pimp’s tough exterior finally cracks when he tries to find the mother of the child abducted by a chisel-wielding serial killer. Na reverse engineers the police procedural thriller, turning it inside out. He reveals who the killer is immediately; it’s just a matter of putting the pieces together and finding out where the bodies are stashed. The narrative spans mere hours, as Na carefully builds tension, selectively deploying ellipses in action for maximum impact. As an action-thriller-procedural, it stands shoulder to shoulder with the works of Michael Mann and Fincher.

Breathless (Yang Ik-june, 2008)

This is Yang Ik-june’s only feature directorial effort to date, and it’s a bit of a passion project for the actor, since he also financed, wrote, edited, and starred in it. It leaves you hoping for Yang to pick up the camera again and shoot another. Breathless is a character portrait of a shakedown thug with a mean streak. He’s a man fuming with rage.

Violence is the main form of communication in the film. Even love is conveyed with force. Using handheld camerawork organically, evoking a veneer of realism for a narrative that is pure melodrama, the film captures behavior: how does a person react to violence? Do they clam up? Do they lash out, fighting against the aggressor? The brutality is self-perpetuating, an endless cycle. The film’s thesis is loudly declared in a few lines by the protagonist: “The fucker who does the beating thinks he’ll never get beaten up. But there comes a day when that fucker gets a beat down.”