“Old pirates, yes, they rob I, Sold I to the merchant ship; Minutes after they took I From the bottomless pit.”

—Bob Marley,“Redemption Song”

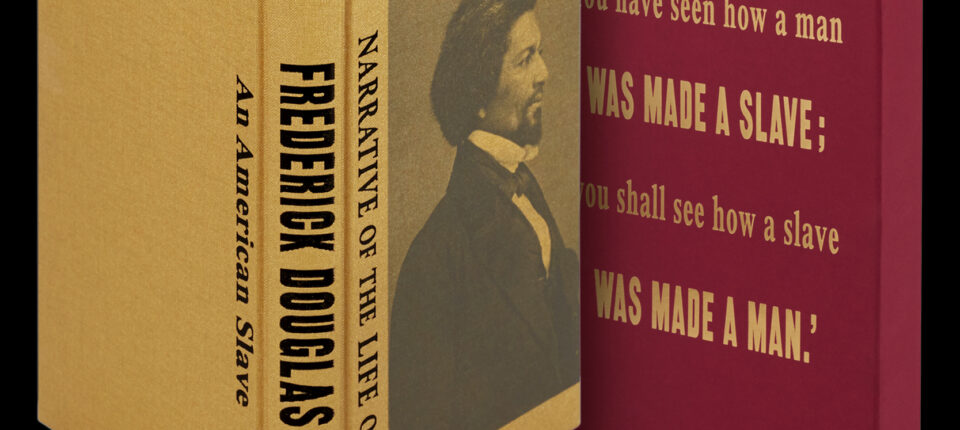

This Folio Society edition of Douglass’s remarkable work marks just another stage in its existence as an intractable work of literature and a public record of slavery and the effort to end slavery. Published in the US in 1845, the book sold well immediately, and its anticipated impact, given its quite radical and bold assertions, had Douglass take flight to the UK upon publication. Whilst there, Douglass would see an edition of the book published in Dublin, and his time there would become a fit subject in the argument for collective global solidarity against oppression that would undergird what Douglass would come to see as elemental to the anti-slavery movement. The Narrative did not explicitly argue a political theory against slavery—it was couched and presented as the written evidence, the testimony for the abolition of slavery. It was to be treated as Douglass had been treated by liberal white people, as the testimony of a victim. Douglass, while in Ireland, could solidify what evidently he had been trying to argue prior to the publication of the Narrative: that slavery was a function of political oppression, and the resistance to it was consistent with global efforts to liberate the poor, the oppressed and the politically subjugated people of the world.

The Narrative was part of a great nineteenth-century wave of similar confessional narratives that formed the arsenal to battle slavery, and was part of the long tradition of pamphleteering that would stand at the core of the American Revolution, for instance. The slave narrative would have its own history of value ranging from the persuasive Biblical epistle, Philemon, to the more recent work of Olaudah Equiano’s slave narrative addressed to the British Parliament. Others would emerge, most of them presented as accounts composed by white people narrators as told to them by enslaved individuals. Douglass’s work was expected to join this march of accounts, and was clearly seen as a necessary adjunct to his own already quite impressive speaking circuit. Douglass, according to contemporaries, was, at the time, quite a fetching figure, a remarkable orator, and a man with a growing sense of his own authority. This volume ends with Douglass’s 1852 speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”, and I believe this is a fitting way to consider the pre-Civil War Frederick Douglass.

Seven years separate the two works (although given the nature of speechmaking by public figures, the seeds and perhaps whole swathes of the work may have long preceded the day normally associated with its first delivery) and these are significant years for Douglass. While they explore similar territory, the position of Douglass as a writer has either shifted, or has been allowed to be viewed through a different set of lenses.

In many ways, the speech is a move towards the more political and strategic manner of his anti-slavery effort. Douglass, in other words, takes on the very political premise of America, and he challenges its most fundamental myth of existence, the formation, if you will, of the nation. He challenges it, and he dares to posit that July Fourth is not, for the African, what it is for the white man in America.

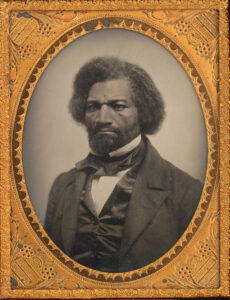

Frederick Douglass, 1856. Quarter-plate ambrotype by an unknown

Frederick Douglass, 1856. Quarter-plate ambrotype by an unknownphotographer.

(National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; acquired through the generosity of an anonymous donor)

In the speech, Douglass offers one of the most eloquent articulations of the basic contradiction of American “freedom”—a fact that has preoccupied so many African Americans since the formation of this nation, and one that continues to preoccupy Black life today. It is the foundational thesis of the phrase, “Black Lives Matter,” for, rhetorically, that term implies that the value of Black lives in America is in doubt. As Douglass points out, the idea of universal suffrage, freedom, rights, and happiness at the core of the American ideal is never quite universal and has never been universal. He does not hold to the view that there is something sacred about the Fourth of July—essentially, the Constitution. Instead, he lays the foundation for the construction of a discourse of enfranchisement and entitlement for the African American, and it is this that would serve as the philosophical underpinning of his proposition and demand that African Americans fight with the Union during the Civil War.

Douglass begins the speech in a manner we have come to expect as a rhetorical device of self-deprecation to laud the audience and downplay the ability of the speaker. He also exaggerates his experience as a speaker, describing the few schoolhouses where he has spoken. Douglass knows what he is doing. “Cling to this day—cling to it, and to its principles, with the grasp of a storm-tossed mariner to a spar at midnight”: It is a fact, that whatever makes for the wealth or for the reputation of Americans, and can be had cheap! will be found by Americans. I shall not be charged with slandering Americans, if I say I think the American side of any question may be safely left in American hands.

Its rhetorical force lies in the most subtle, yet persuasive of devices—the function of voice, of person. Douglass is addressing his audience, and he employs the second person in a manner that seems natural and conventional, yet what becomes increasingly clear is that as he embarks on his subject his decision not to employ the first person plural—the patriotic “we”—represents the foundation of his radical articulation. Douglass, therefore, distances himself from this version of America not just as speaker, but as one who is disenfranchised, one who is not part of the narrative. It is not humility: it is chagrin and indignation. Thus, after presenting the heroic values of America and its founding fathers and their work and efforts, he shifts the voice by explicitly setting himself apart from those he is addressing, and by extension, those who represent the America that he is not part of. Suddenly, he introduces the first person plural, and it is not the “us” of America, but the “us” of the humble and unworthy “I” who has been speaking. This “I” is declaring that his plurality is a whole different set of people, and is the enslaved, the African American, the true “we” of his subject: “Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us?”

From then on, the “you” and the “our” become clearly marked. The speech is now confrontational and settles into its most powerful rhetorical position: “I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us.”

Just as quickly, he asserts what his tribe is, and when he speaks of the first person singular, he is speaking of the first person plural; he is, then, speaking for a nation, a realized tribe of the suffering: the lashed, and the killed. It is a shift that has proved to be the hallmark of revolutionary speeches. When Bob Marley sings in “Babylon System”—We refuse to be what you wanted us to be We are what we are, that’s the way it’s going to be . . . We’ve been trodding on the winepress much too long,—the lines are drawn. And my inclination to allude to reggae music may be explained by my proximity to music as someone raised in Jamaica. Yet the connections would not be lost on anyone who has a small understanding of the history of slavery and resistance in the New World, and the role of the Jamaican in the shaping of a discourse of protest around that legacy, symbolized most clearly in the United States in the person of Marcus Garvey.

Douglass makes it clear that the enslaved are on the side of the angels. His logic is searingly blunt, and he admits the absurdity of having to prove what is most obvious and understood. His anger arises from his view that he is not arguing a case that needs to be proven—the wrongness of slavery and the humanity of the negro—but that he is facing an adversary who is a hypocrite and who is morally bereft while pretending to a set of values that are lofty and right. He is, in other words, vexed by the very fact of this Fourth of July and all the celebration it engenders, while he and his people continue to be held as slaves: “For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake.” This speech is incendiary and unabashedly so. It is confrontational in a manner that the Narrative does not rise to.

Perhaps the striking difference between the speech and the Narrative is the matter of patronage and ownership. Set against the patronage of William Lloyd Garrison and Wen- dell Phillips, who both wrote prefatory pieces to the Narrative, Douglass seems to feel the burden of his responsibility to them, one that is jettisoned altogether by the time of his speech when he alone stands before the crowd, and allows himself to carry the weight of that responsibility.

As a revolutionary, Douglass has arrived by 1852 at a point where he is willing to address the very foundation of American power—its political and judicial institutions, and its religious institutions. He is no longer interested in the slaveholder; he is more interested in the legislators, those who have continued to work hard to retain the infrastructure and economic possibilities of American Slavery, as he calls it. And so here, he stands in danger of sedition, and this is not a fanciful notion. This, in other words, is fighting talk:

The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

His answer to the question, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” is a searing diatribe, made most compelling by its unassailable moral argument, but made most startling by its temerity. I expect that even the most committed abolitionist would blanch at Douglass’s words:

To him [the American slave], your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass-fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.

In the end, it is clear that Douglass has fine-tuned his quarrel with America along very specific lines. The hypocrisy of the American nation is the central and most developed case that he makes, and it rests in the perpetuation of the “Internal Slave Trade,” supported and sustained, as he says, by “American politics and American religion” and viewed by these institutions as an honorable economic practice, while investing words and funds towards upbraiding the Atlantic slave trade. Douglass lays out all the core acts of American law, including the Fugitive Slave Law, that perpetuate this hypocrisy and inhumanity. Then he takes on American Christianity. This is a subject that consumes Douglass again and again. It is one that concerned him when he wrote his Narrative, and when he later reflected on what he had written there:

But the church of this country is not only indifferent to the wrongs of the slave, it actually takes sides with the oppressors. It has made itself the bulwark of American slavery, and the shield of American slave-hunters.

The speech ends “with hope”, he claims, but from this side of history, we know that the gloom that overshadows this hope and this faith in the change to come is marked by the incredible and bloody tragedy of the Civil War. Douglass presages the fact of it with language of forces that are at work to create this change, and in the fact that he knows that the ending of slavery will have to be by violent means and will require a seismic shift in the identity of the nation. The end of slavery was not driven by the acceptance of the humanity of the enslaved—not, at least, in the oratory of the leaders of the nation, and certainly not by Abraham Lincoln. Instead, it is Douglass’s words that would set the stage for the century that will follow.

It’s impossible to read the original prefatory salvos to Douglass’s autobiography without sensing quickly the compelling circumstances surrounding the publication of the book and the very existence of this figure Douglass. There is little question that William Lloyd Garrison was a radical, a deeply committed abolitionist, and a man who dared to challenge the very legitimacy of the American government on the basis of its persistent engagement with slavery. Garrison takes credit for introducing Douglass to the world; he recognized his genius and he pushed him to become a professional lecturer.

Yet what is absolutely clear is that behind this seeming generosity is a peculiar and striking pragmatism—the radical logic of a political risk-taker who is so complete in his belief in a cause that he will see only two kinds of people in the world—those who share his views and those who are his enemies and, by extension, enemies of his cause.

The anti-slavery movement was an illegal cause pushing against the law of the land. He recruits Douglass because Douglass would be, he explains, a unique weapon. When he reports that Douglass is resistant, reasoning that he may cause more harm than good by being a fugitive slave and holding so high a profile, his agent and benefactor work hard to push him forward. The cause is greater than Douglass. At points, I’ve gotten the impression that the cause is greater than the liberation of the enslaved. The cause, instead, is what has crystallized into a doctrine, a creed, and this fundamental arguing, offered in the discourse of evangelical Christian thought and faith, rife with the presumptions of the inferiority of Africans, drives this man who is our introducer of Douglass.

The logic is simple: slavery has been so pernicious that it has debased Africans so much so that they are morally, intellectually, socially, and spiritually bereft and inferior. He makes a point of the theory that, were white people subjected to slavery, they too would be as inferior as the Black man. Douglass constitutes an aberration of sorts, but one does not have the impression that Garrison considers Douglass an equal. The African, like Douglass, needs help and the first stage of this help is the ending of slavery.

In the arsenal of the anti-slavery movement, Garrison has an acute understanding of the extraordinary power that Douglass constitutes. He is a Black man, he is a good-looking Black man, he is articulate and literate, he is still a fugitive, he had been for most of his life thus far a slave, he is willing to name names. This is a gold mine. Garrison goads the southern planters to challenge Douglass, to sue, even. He dares them to come forward and refute his story because he believes that they will, by responding to any of the fugitives’ claims, implicate themselves.

After the flourish of the preacher man who appears to throw caution to the wind, it is Wendell Phillips who reminds us that the entire project, the book, the lecturing, the ferrying of Douglass across the northeastern US to speak up against slavery and the necessary rituals of protecting Douglass is, in a word, illegal—a crime. He allows us to see that those like him who have supported the cause are savvy people, fully aware of the idea of deniability and the mores of people working under the law. The conspiracy of the Supreme Court’s decision to not only allow slavery to stand but to make it a federal law to aid and abet an escaped slave made all implicated in doing so subject to persecution. This was the context. It is not strange then that one is at once impressed by the willingness of these two men to take risks and still by their patronizing posture are able to position themselves as the heroic figures in the drama. They also happily “own” Douglass as a voice. In other words, he will write his story for these very people. When Douglass publishes this book, his biography is no longer his. It is an argument, a symbolic position. Like Equiano, Douglass accepts that his story is a tool of doctrine. Douglass, like Equiano and a host of other witnesses and victims of slavery, frame the narrative construction of the African American in America for the next two centuries. The presumed value of their story is to affect some grander change, to defend the humanity of the Black persona, to demonstrate that they are also human, and to translate for the white world the inscrutable story of their existence. It is a peculiar American lineage that keeps repeating itself whether it is the story of Douglass, Bigger Thomas, Maya Angelou, Malcolm X, or Will Smith.

The construction of the Narrative is calculated to have the effect of a series of arguments against slavery. Douglass knows that he himself is functioning as the best argument because he is a witness, a principal in this grand drama. Each circumstance is the basis of an argument. The fact that he does not know his father, and that there is speculation that his father may be his master, presents Douglass with the opportunity to explore the ways of white slaveholders who coldly reproduce themselves by sleeping with enslaved women, and then subject them to abuse, to sale, and to the anger of their wives. The laws of slave states arise at various points in the Narrative to show how dire the circumstances facing the enslaved in America are rehearsed. He points, for instance, to the inordinate number of laws that sanction the lashing of the enslaved and the execution of the enslaved (in his speech, Douglass identifies in Virginia seventy-two infractions in the law that warrant the death sentence for the enslaved, and only two infractions for the death sentence for the white man). Douglass’s compelling case is that there is no justification for slavery in a civilized society. Yet, he is also acutely aware that the very act of writing and publishing his book constitutes an act of resistance, a crime. He is fighting back by his very existence, and he understands the risk he is taking.

He fully appreciates that the core infrastructure of the slave system is to staunch resistance, but more than that, to build a bulwark predicated on violence, and the systemic construction of a violent society to stop the natural inclination of the enslaved towards seeking some kind of redress. And the acts of this society, which he details in this work, are ingenious, devious, and cynical. Even something as seemingly humane as the holiday for the slave is designed to be part of this elaborate system and to cause damage to the slave. The planters understand that the partying between Christmas and New Year is a great killer of resistance and rebellion. The slaveholders like to keep the slaves drunk, make them glad for this holiday and will do everything to make the slave drink to excess. The angry slave was made drunk. “Be slaves to man as to rum.” The games of brutality are quite remarkable.

For Douglass, studying the deceptive ways of the master allows him to carry a sense of superiority even in the midst of his suffering. The slaveholder is always finding a way to make every moment for the enslaved be one of choicelessness, or a choice between two decidedly unhealthy options.

Douglass begins the Narrative with a somewhat subdued assessment of what he describes as the Southern religion, but it is clear that he is suppressing a significant chagrin, for eventually, in chapter ten, he explodes into his most extensive diatribe against the hypocrisy of Christian believers who are slaveholders. This is one of the most remarkable passages in the work, for it drives deeply into the heart of white American ideals. For Douglass, the core characteristic of the slaveholder and the slave-holding class of white people is hypocrisy. This notion is critical to his larger thesis. Hypocrisy is not predicated on the lack of knowledge but, on the contrary, on the availability of knowledge and understanding, and the willful act of subterfuge and pretense that knowingly uses the guise of Christianity to justify the inhumane treatment of African people. He states that of all the slaveholders he ever encountered, the worst were those who claimed to be and were accepted as the paragons of their Christian faith. They were reverends, preachers, pastors and church leaders of great standing. And they were debauched in their attitudes to slaves and slavery, driven fully by greed and by moral terpitude. Tellingly, while there is the prevailing perception that the main sect responsible for this hypocrisy in the south was the Baptist, in Douglass’s account it is the evangelical Methodists, at the time, quite radical in their revival sensibility, who dominate this narrative. This may be a regional distinction, but in Georgia, Virginia and Maryland, Douglass references Methodists. He would have known that it was Methodist converts driving the abolitionist movement in Britain, and so his disappointment in the Methodists of the south is acute.

Douglass’s analysis of religion and slavery is damning and brilliant. For him, the very civilization of white America, predicated on the notion of Christian faith, was at best a grand demonstration of hypocrisy, or at worst, a philosophical failure of the most profound type. His view was that Christianity, rather than tempering or even softening the impact of slavery, in fact strengthened the institution and all its brutality. This power would continue well into the twentieth century, and still haunts the discourse around faith and morality and race today.

Douglass then turns his attention to making a case for the humanity of the Black man, and discusses the internal life of the slave with a very brilliantly detailed account of the psychology of melancholy and despair. He makes clear that the dehumanizing of the Black person through stratagems of brutality constitutes the diabolical force of slave society and its function. Douglass reminds us again and again that whenever he was made busy, too fatigued by the labor to find food, unable to think, to feel, even, he lost interest in fighting for his freedom. And whenever he was well-cared for, whenever he was fed, whenever he had rest, then what he desired was not to be thankful to his master, but to be free. In this sense, Douglass was confirming the views of the enslaver. But he also points out that it is feeling, love and affection and the desire to stay close to family that made some slaves reluctant to flee. For Douglass, the impulse to freedom is innate—it is part of what makes humans human. The enslaved person who remains in slavery is an aberration, and is someone who has been broken into this state.

Perhaps the most striking articulation of this remarkable document happens to arrive as an addendum—a corrective to what he feared might have been a misapprehension of his attitude to faith. He rightly discerned that readers would have picked up over the course of the Narrative an unabashed apathy towards religion. Douglass made it clear—he preferred a non-religious slave master to a Christian one, the latter being brutal, violent, vile, hypocritical and self-righteous in their unrighteousness. Rather than modifying and even softening this perception, Douglass devotes the entire appendix to double-down on his criticism. He makes it clear that he is speaking of American Christianity. He makes it clear that he is not selective about the sects and denominations. White American Christianity, whether in the south or the north, is corrupt, debased, and more perfectly associated with the religion of the Pharisees and the Sadducees than with the pure religion of Christ. With ruthless but brilliant rhetorical aplomb, he lays the case out. It is a tour de force of preaching. It is a jeremiad that implicates the very foundation of American racism. And what is most arresting is how it all seems to ring true today.

Douglass remains relevant in the twenty-first century because of his ideas and also because of the manner of his impact on the nineteenth-century American imagination. One has little reason to doubt the scholarly claims that he was the most photographed person of that century given the vast number of portraits of him that remain available to us. This fact would be one thing, but there is also clear indication that he was calculated about being photographed because he understood that the photograph was a weapon for his work. He understood himself to have a striking visage, was aware of his photogenic look, and he would make complete sense in our present culture where the image constitutes a significant power in the construction of success and influence. It is not difficult to extrapolate that Douglass would embrace and make full use of viral culture were he alive today.

Yet there is more to this phenomenon. At the core of Douglass’s entire rhetorical position is the case for the humanity of the negro. In speech after speech and in his writings, Douglass would ask the question, “Am I not a man?” The face shown is in contradiction to the caricatures, the cartoons, the mocking buffoonery of minstrelsy Douglass knew that he was defying by each moment of his presence in a photograph. The photographs were the evidence of his manhood, his humanity, and his ubiquitous presence in the imagination of the white world. Yet, built into Douglass’s trading in his look is a certain less-explored question of the notion of beauty as it intersects with race in America. Douglass’s mixed-race heritage and accessible beauty was also being traded in these images, a way to symbolize his acceptability as a human being.

Think of the ways in which Barack Obama’s heritage and his position as a mixed-race individual complicated his appeal, allowing white America to feel a certain ownership of him. Before Obama, the face and person of Bob Marley was employed in a similar manner especially after his death when his white biographers created a myth of his otherness from Blackness and his latent whiteness as part of his appeal, and part of the justification of their ownership of him, despite his clear anti-white rhetoric. The face of Douglass, the image, as it were, of Douglass, captured in these viral photos, cannot be separated from any understanding of who he was and what he would come to represent in America. Yet, Douglass was not only speaking to white people with his photographs. He was also taking hold of his Blackness—his belonging as an African. His features draw attention to this seeming ambiguity—making him at once a comforting figure to whites, as well as a clear figure of Black masculinity to the Black population. One need not overstate the fetishization of race that is directly tied to his photo-narrative. These images, reproduced in newspapers, magazines, postcards, and posters, traveled further than Douglass himself could.

In this sense, Douglass became a haunting. There is an audaciousness to this use of his image. During the years when the Fugitive Slave Law was still the law of the land, he was constantly in danger both as a fugitive and as a man speaking against the forces that sought to protect the economy and ethics of slavery. He was never anonymous and risked a great deal by being known, being seen. In his calculation, this was a price he would be willing to pay. Yet, if one understands these portraits to constitute symbols of success, of wealth, of respectability and of power, it does make a great deal of sense that he would encourage their propagation. He sat for over 160 portraits. These were not snapshots. These were orchestrated and calculated events, and Douglass mobilized his image as a weapon, as an affront to white supremacy.

This new edition of the Narrative, sadly, is timely. The circumstances of our time, and the persistence of the effects of American slavery, and the struggle for the equality of people of African descent in the United States and around the world, make this work still relevant today. It offers a challenge to the United States and other nations, and to the principles that undergird current efforts to address the effects of the brutal legacy of slavery. It is important to note that Douglass was faced with the very same context of America’s idea of itself both in his Narrative and his speech. And this America is essentially one defined by the idea of whiteness, and one then that enshrines the core values of freedom from tyranny, the nobility of the founding fathers and their ideas, the principle of a Christian nation, and the condition of Africans in America. Whether he intended to or not, then-president Donald Trump’s comment on Frederick Douglass, framed in language that would suggest that he believed Douglass was still living and doing his work, constitutes one of those accidental instances of value that warrant some note: “Frederick Douglass is an example of somebody who’s done an amazing job and is being recognized more and more, I notice.”

__________________________________

The Folio Society edition of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, introduced by Kwame Dawes, is exclusively available from foliosociety.com