In crystalline prose, The Lookback Window opens on a sun-dappled resort, but dread seeps through. When the Child Victims Act goes into effect in New York State, a yearlong lookback window opens, allowing now adult victims to sue their abusers. Reading about these cases, Dylan’s life is thrust open. As a teenager, he was the victim of sex trafficking. Now in his twenties, confronted with the opportunity to seek justice, Dylan revisits the past and descends into the deep well of his emotions.

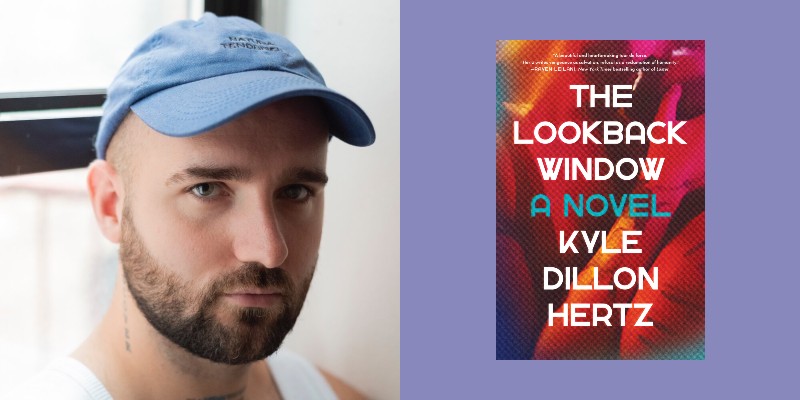

Written with rage, sex, pain, and understated dark humor, Kyle Dillon Hertz’s The Lookback Window is a powerful examination of our culture’s response to sexual violence against men. Through its close attention to the lives of men healing from abuse, the novel searches for what justice can look like in our world today.

Kyle Dillon Hertz is a writer based in New York. He spoke with CrimeReads about the novel, the power of language, and his thoughts on heroes and villains.

Michael Colbert: In his relationship with his husband, Moans, Dylan often feels himself slipping away. He tells his therapist, “I’m afraid that if I don’t lose him I might never get to be myself.” How were you thinking about codependence in their relationship?

Kyle Dillon Hertz: Dylan was young when he met Moans. A lot of my friends leaving their very late teens and early 20s, especially my queer friends, ended up in these relationships with much older people—and not bad relationships, nothing TikTok would make a fuss over—but in these relationships, they did placate or play to someone a bit older, who helps them get through. I think part of the quote is that when you’re young, good looking, and you find these people who want to be with you, you play to them.

The other part is the lookback window. All the different characters in The Lookback Window have a different philosophy of healing from trauma. You have Dylan, who eventually gets quite angry and confrontational. And then you have Moans, who also grew up in a quite traumatic environment, and due to the religious way he was raised, due to the ways that his family learned to survive, he represses or suppresses the reactionary, revolutionary, confrontational feeling that Dylan learns to heal with. I’m not necessarily saying one way or the other is better, but in this specific regard, you see how two ways to potentially deal, live with, and heal from trauma play with each other.

MC: Did your characters develop from an interest in examining those differences, or did those differences develop organically?

KH: I think in many ways organically. For a novel to work for me, you need oppositional figures. I think a lot of writers occasionally look at things in terms of hero and villain, which I just do not find compelling at all. I actually fucking hate our world that is so into this: the Marvel issue, the Harry Potter issue. This kind of thinking and plot is so absolutely boring to me, and I just find it useless. To me, a better way to think of it is oppositional forces. The more oppositional forces that are within the narrative, the greater the opportunity for character, for plot, for growth there is. I find that is in many ways true to real life as well. You have an issue, and you talk to your friends, they have a different opinion than you. That’s how the world works to me; it’s a series of oppositional forces. In your background, is that The Leftovers from HBO?

MC: Yeah.

KH: To me, that’s one of the greatest shows that exists. I wrote most of this book to the Max Richter score. That show also does that thing where there’s no real villains. You have these eight people who are dealing with grief in different ways, and [the show looks at] how it interacts with each other. I find that narrative work fascinating, compelling, and in many ways true as to real life.

MC: That feels true to Moans and Dylan; they reach an impasse because of how their responses interact. Instead of hero and antihero, how did you think of Dylan as you wrote?

KH: I thought of him as a victim with what I believe to be righteous anger. Instead of trying to fit these tropes into a book that does not play by the rules of them, I wanted to follow someone on their path to healing from this very specific thing, which in Dylan’s case involves being quite angry, quite confrontational. To me, that’s extraordinary. There’s a part later in the book where Dylan talks about wishing he could grant other people their anger without judgment. I know many people in my own life who if they just allowed themselves to be angry for actually grievous harm would probably have a bit of a better life. In some ways, I find Dylan to be a little heroic in that regard; he is attempting to live in a way that would benefit a lot of people: to permit each emotion its due and not just suck things up to make the world better. The world is a really shitty place, and what happens to these characters is often really shitty. What little wrongs Dylan does, Moans does, Alexander does, James does, these are little wrongs in a world of gargantuan wrongs. That’s not in the realm of hero and villain. They’re all people who have been harmed and are attempting to account for that harm.

MC: There’s a really interesting passage on the power of language and the use of the words victim and survivor: “Language has reached its peak. We now live in an age where people claim words designed by people who want them to suffer…This is not the age of degradation, but the age of language surpassing sound and becoming a product.” What power can language have for people, and how does that get blunted by misuse?

KH: Languages are a living thing to me, in many regards. I freely use the word faggot. This is a word that my friends and I use. This is not a profane, horrible, nasty word when we use it in this regard; of course, it can be used in that regard by other people. It’s complex, right? On one level, in that moment, I was permitting Dylan to play around with language, attempting to come to some idea on what it means to be a victim. I do think in many regards the use of the word survivor is so fucking annoying. It’s like when you go to a bookstore, and you see a used sticker slapped onto a book. It’s this labeling that sort of permits this thing to still be read but also qualifies the fact that it’s been handled before, and maybe handled roughly, so you can pay a little less for it. I find that word “survivor” to be in that territory for me. I just don’t use it. I find it annoying. I find it frustrating, and I sometimes think that the identity around survivor does more harm than good.

Here’s an example of that. In New York State, you’re a crime victim. You can go to the Crime Victims Treatment Center. The use of the word victim in this regard is pointed towards services. It blows my mind that people don’t know if you get attacked, raped, or molested in New York, there’s a place you can go to as a victim for free therapy. Then through the Office of Victim Services, you can get any financial burden like your therapy reimbursed. All of that is wrapped up in the word victim, where there are real things that it’s going to do. To me, the “survivor” word is pointed toward Instagram hashtags. It’s pointed toward TikToks. It’s pointed toward this thing that denotes an identity among people rather than a whole world where you can actually maybe heal. The word survivor pisses me off a little bit, and Dylan takes it much further than that, but I think there’s truth in what he’s saying.

MC: This book looks directly at violence against men. Are there any conversations you hope this book opens up?

KH: I hope first off that people read the book and get some kind of enjoyment out of it, whether that’s the language, whether it’s the genre, whether it’s the explicitness, the sex, or the ideas. This book really does discuss sexual violence in men, which is barely any different from sexual violence among women. For example, the FBI didn’t even include that rape could happen between men, I think, until 2013, so when we’re talking about statistical differences, it literally wasn’t even legally a definition until 10 years ago, it wasn’t even a question being asked. I hope in many ways what the book grants people is language to talk about these things. Sometimes I do think it’s easier to hear from a character who speaks way louder than you ever will, who says maybe a bit more intense things than you will in order to give you a framework to push back against, to maybe steal some things from, and most of all, to feel something from. These things have deep, real world consequences. These are deeply felt things that I think and care really deeply about.

I hope that anybody who reads this book, especially men, especially queer men, really get a chance to feel like, “Okay, fuck, I have had these experiences. I’ve had these similar things happen.” I’ve had so many people through writing, editing, talking, and having read this book, be like, “This thing happened to me. And I felt like a) I couldn’t tell anyone, b) the people I told I didn’t care.” I think a lot of people in the world don’t even have a framework to understand male sexual violence. I think people do want to care. I don’t think people are that fucking nasty and cruel, but I don’t think people have a framework to understand that. I hope this book frees someone up to talk about that.

MC: You said Dylan’s speaking a bit louder than someone else might. What was it like writing his anger?

KH: I think the book really does not start in quite an emotional place. Dylan’s journey is really a journey toward a) understanding what emotion he’s having, b) feeling it and then c) after many years of repression, due to childhood sexual abuse, actually experiencing it. Once he experiences it and really understands what happened to him, he has a very deep well to draw from, which from a writing perspective was great. It’s an amazing thing to have that kind of wealth to draw from.

The anger of this book has been spoken about in a lot of different interviews, and one of the things people say is, “I actually haven’t read that many contemporary angry books,” which is a funny thing to hear, because I guess I really haven’t either, although they do exist. I’m really angry at the world. A lot of my friends are really angry at the world. It is really difficult to look at this shit and be like, “I’m cool. This is all great.” For me, it felt honest to write an angry book because I’m angry. It felt good to write something honest and not bullshit like four friends in Brooklyn talking over tea, because that’s not a world I recognize.

MC: Your book opens with a Lana Del Rey epigraph. You received a review that compared the novel to Norman Fucking Rockwell. Why does her work resonate with you and this book?

KH: The book is a very American book in many ways. It deals with the American justice system. It has a very American way of speaking. It’s completely and totally profane. Lana does that as well: American iconography, American language. She’s talking about her Pepsi Cola pussy. She’s talking about fucking daddies—it’s that kind of American way of writing that taps into classics and nature but also is completely prone to fits of explicitness. I specifically set out to allow myself that. The other thing Lana does really well—she draws from different genres. This book in some ways has been hard to classify because it draws from mystery, it draws from crime, it’s literary fiction, it’s a romance, it’s pornography. It draws from all of these different genres, and she does that really well.

MC: This book moves from New York to Fire Island, and in its depiction of these settings, I was curious if you had any gay literary influences.

KH: I’m a huge fan of Andrew Holleran. I think Dancer from the Dance is one of the greatest books ever written. My book is very different from his; the voice is very different, but he can be explicit. He sets it in a queer world, and my world is a queer world. Everyone I know is queer. I wanted to write for them and not for the people who would be shocked, which is something that Andrew Holleran does, as well.

There are some other contemporary people like Kyle Carrero Lopez, who writes these great, queer poems. There’s this one other book I love called An Arrow’s Flight by Mark Merlis. He wrote a retelling of the AIDS crisis set in ancient Greece, but it’s bizarre because it’s a contemporary Ancient Greece. It’s a fucking insane book, one of the best books I’ve ever read. There’s this one part in the middle of my book that’s a retelling of the fall of Apollo on Fire Island while the characters are high on shrooms and attending orgies. That one little bit in some ways is my love letter to Mark Merlis.

MC: What’s interesting to you right now in fiction, whether in your reading or your own writing?

KH: The new book I’m working on is a a queer World War Two novel on Paragraph 175. Tons of gays in the Holocaust were killed in prison. Paragraph 175 was this law that if you were gay, you went to jail. Upon the liberation of the camps, the gay prisoners were put into German prisons. Part of the reason why there’s barely any accounts of what happened to queer people in the Holocaust is because a ton of them were killed, and then beyond that, they were put in prison. I think with what’s going on in our country right now, Paragraph 175, the criminalization of queer people, has been so much on my mind.

On a more positive note, I’m kind of obsessed with people who do different types of books, like people who jump from one subject to another. Percival Everett is one of them, who I’m obsessed with right now. And Colson Whitehead is, of course, extraordinary. The ability to shift genre is something that I find really fascinating.

–This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.