When I first had the idea for this interview series, where I’d talk to well-known crime writers about the books that they think every fan should read, it seemed self-evident that I should start with Ace Atkins, the award-winning, New York Times bestselling author of the Quinn Colson series. As every writer who has interacted with him knows, Ace is a fount of knowledge when it comes to both the craft and history of crime fiction. (He and writer Megan Abbott have a regular meet-up online where they watch noir movies together and then discuss them, an event that would surely sell out within minutes if they ever felt like opening it to the public.) Atkins is unfailingly helpful to new writers, generous with his time and advice, and always willing to discuss the genre he loves.

He’s also deeply rooted in the life and landscape of the place he’s lived for the past twenty years: Oxford, Mississippi. Universally associated with the work of William Faulkner, north Mississippi has become almost as well-known among readers of crime fiction as the home of Atkins’s Army-ranger-turned-sheriff, Quinn Colson. When Atkins moved to Oxford twenty years ago, it was the home of writer Larry Brown, the two-time winner of the Southern Book Award for fiction who died in 2004. Brown overlapped with Faulkner at the beginning of his life and Atkins at the end, and his work is immersed in the same rural noir tradition of dark nights, startling violence, and fierce loyalty to family and place.

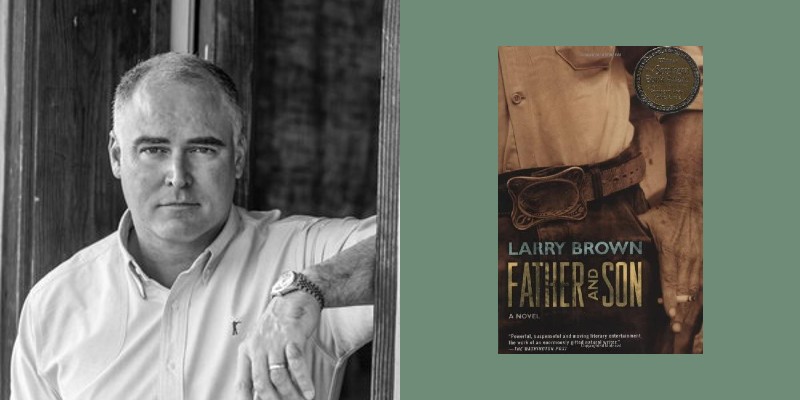

For my first interview for The Backlist, Atkins and I sat down to talk about Brown’s novel Father and Son. The novel tells the story of Glen Davis, a felon recently released from Parchman Prison who returns to his hometown intent on wreaking vengeance on nearly everyone he’s ever known. Glen’s penchant for violence is contrasted with the humanity of the new sheriff, Bobby Blanchard, who grew up with Glen and has more in common with him than most in the community realize. Published by Algonquin in 1996, Father and Son, like most of Brown’s novels, is currently out of print—a fact that Atkins regrets, given Brown’s outsize influence on him and other Southern writers of his generation.

Author Larry Brown

Author Larry Brown

Tell me about your friendship with Larry Brown and his influence on your work.

When I left the newspaper business, I pretty much could have lived anywhere. One of the reasons I chose Oxford was because Larry was here, and Barry Hannah, and so many other great writers. It’s not like we sat around and had deep conversations about writing or anything like that, but it was just nice to be among your heroes. You walk up to the bar, and there’s Larry hanging out, drinking. And then when I read Father and Son, which is my favorite of his novels, I thought, “This is the kind of stuff I want to write.” Until I reread for this interview, I don’t think I’d fully realized how much it influenced me. The feel of Oxford has changed a great deal since Larry’s time, but when I read Father and Son again now, I know every single location he’s talking about. I know the family names. A lot of the novel takes place around Tula, where Larry lived, and also around a town called Paris, where I have a farm, so it’s very specific.

If he was writing about real places and even using real names, how was that received by the locals?

That’s a good question. I think people just thought it was kind of odd, that here’s this former fireman on the front page of the New York Times book section. I think maybe some of the people who were surprised by it did not understand technically what a great writer Larry was. He was almost entirely self-taught. He’d audited a class with Barry Hannah at Ole Miss, but the majority of what Larry knew about craft he’d learned by just working at it. When I read his fiction, it makes me think of someone like a car mechanic or a carpenter, who just works his butt off until he gets it right. Every sentence is just sharp. Every piece of dialogue is perfect. It took a really dedicated mind to create something like this.

People ask, “What is literature?” and “What is genre fiction?” and all that kind of crap. And certainly this is one of those books that is absolutely both. But the important thing is that it’s a narrative that you just can’t put down, so much so that I almost reread the whole thing in one sitting. It starts with this guy getting out of prison, he’s back home, and we know things are not going well. We know that this is a bad guy. Glen is somebody who’s on a path to hell. He’s a really dark, unrelenting character, and it’s flat-out terrific.

I think a lot of modern crime writers would try to give Glen more of a tragic backstory to explain his actions, but Brown doesn’t make that choice.

That’s right. An editor today, or especially someone in Hollywood, would say, “Why is Glen the way he is?” And the answer is, he’s just a rotten son of a bitch. He’s an awful person.

I was talking to Megan Abbott recently about film, and she mentioned a director that she was not really fond of. She said, “I remember seeing his movies, but I can’t tell you a thing about them.” I knew exactly what she was talking about—there’s not a single moment that really sticks with you. Father and Son is the opposite of that for me. It’s so real. When my wife and I first moved to Mississippi, we bought this old farmhouse deep in Larry Brown country. Sometimes I’d see a beat-up truck just come out of nowhere, with a guy with his arm hanging out the window smoking a cigarette, and every time I’d think, “There goes Glen Davis.” That kind of imagery is part of Larry’s genius. You just can’t shake it.

Everything that you’re saying about Brown’s work could also be said about Faulkner’s, and also about yours. What did Brown teach you about adding that kind of texture to fiction?

I appreciate you comparing my work with those two guys, because they mean so much to me. And I think they mean more to me after so many years of living in this county. The idea of taking a small community, and focusing in on the family connections, the boiling-up of hatred and revenge that can seep into some of these relationships over the years—that’s very specific to the South and to Southern literature. Sometimes people have the idea that the Southern story is Steel Magnolias or The Help or something like that, but to me it’s a very haunted place with a very dark and exceptionally violent history. I’m originally from Alabama, but when I got to Mississippi, it was on another level. I don’t want to say uncivilized, but it was. You could go up to a gas station and see a horse tied up to a post. When you think about these Western tropes of an outlaw out on the back roads and a sheriff trying to find justice, that’s still real here. I was out on a county road right before Christmas, and there was a woman outside boiling her laundry because she didn’t have electricity. People talk about Oxford being a quaint little southern town, and it is, but I can take you a mile in any direction and you’re back in the nineteenth century.

How do you think Larry would feel if he knew that we were having a conversation about him as a crime writer? Would he have described himself that way?

I don’t think Larry would have thought of himself that way. He cared about writing a good story, and I don’t think he ever thought about how it was going to be marketed. It’s the same with Faulkner—he never called himself a crime writer, but there’s a theme of crime and detection in a lot of his books, and I would categorize both Sanctuary and Intruder in the Dust as deep Southern noir. You see the relationships of the families out of the county and the interconnectedness of the histories of these people, and the ever-present violence in some of these small communities. Stylistically, Larry is nothing like Faulkner, but as far as the subject matter goes, it’s spot-on.

Father and Son has five murders (six counting a monkey crucified with an ice pick), three accidental deaths, a suicide, a case of child abuse, and two pretty violent sexual assaults. Do you see this level of violence as an expression of what Larry Brown saw around him in rural Mississippi, or a way of keeping the plot moving, or a nod to genre conventions—or all of the above?

I can’t really say what Larry would have said about why he did that. I can say that I’ve spent a lot of time riding these back roads with sheriff’s deputies, and this county has its share of Glen Davises, who just want to burn everything down. I could walk down the street to the jail right now and find you at least a couple Glens—just unhappy, evil people that are seeking to destroy what’s around them. I don’t think Larry was trying to shock anybody. He was just writing about the darkness of the world around him.

This discussion makes me think of what Charles Baxter writes about melodrama, which he defines as “the scene of the incomprehensible attached to the unforgivable.” He says that there’s a tendency in modern fiction to pretend that all human behavior can be explained, but that’s failing to acknowledge that there are truly bad people in the world.

That’s true, but I think Larry was also writing about something he recognized in himself. Not the darkest and most violent aspects of Glen’s character, but in some of the self-destructive tendencies that he had. I think Larry knew that his life could have gone in a different way, if he’d made different decisions.

Most of the violence is instigated by the male characters, but there are two significant female characters in the book, and one plays a key role in the very violent climatic scene.

Well, it’s not a rosy ending. It’s not like the bad guy is killed and all is right with the world. Glen burns down the world and everything that he comes in contact with, and nobody is ever going to emerge clean or unharmed from his path of destruction. But that final scene with Mary, Bobby’s mother, shows the strength of that character and the resilience of that character. Larry doesn’t have an ounce of exposition in the story, which is wonderful, but you get the sense that she’s had trials and tribulations in her life, and she’s tougher than Glen is evil. She’s the toughest character in the book, even more so than her son.

Is there anything that we haven’t talked about, any scenes that stand out to you that you were excited to go back to? Or just things that come to mind?

Well, we haven’t talked about the crucifixion of the monkey. It’s so shocking, and so violent, and if you read this book, you’ll never forget it. I love the scene after the monkey is killed where Glen is driving around, and you think he’s going have some kind of remorse for what he’s done. And instead of having remorse, he says, “I wish that monkey was alive, just so I could go back and kill again.”

That seems like O’Connor to me—this extreme grotesquerie that’s never explained.

That’s great Southern noir. It’s grotesque, it’s violent, it’s absurd. I think that Larry brought back some of those darker elements to Southern literature that maybe had been eroded since the time of O’Connor and Faulkner. This is a place that was founded in violence and slavery and brutality, and the ripple effects are still with us. And Larry was very well-aware of that. When I talk to people in Oxford, there’s still so much admiration and so much love for the guy. He was only fifty-three when he died, and it was such a shock. I hate to see these books out of print, but I think his influence is massive. If you look the writers down here like me, and Tom Franklin, and Michael Farris Smith, and Bill Boyle, we’re all trying to keep that tradition alive.