So, the world closed in on us, right? And while lockdown may have had less of an impact on writers than it did on office workers, chefs, or elementary school teachers, it did mean that those of us who need a crowded coffee house to focus, or who depend on travel for research (honest, it’s entirely for work!) found a lot of doors slammed shut in our faces.

The book I’d intended to write was to take place in Paris and the Dordogne. I had been to both places before, and I thought I might be able to fake it, but I knew I’d have trouble when it came to the things that matter—the sensory elements, the geographic oddities that aren’t apparent until you walk the city streets, the seasonal contents of the markets and the architectural personality of the districts and the quality of the light and the air and the accents…

Of course, things might open up—if everyone got vaccinated, if the shots worked well, if the problems just went away.

But while I thought about it (as if there wasn’t plenty to think about in the waning months of 2020) I also became aware of another door that I’d been vaguely aware of for some time, one that I wasn’t ready for, one I knew would be a risk.

A sealed door was more or less how I started in the first place (minus the world-wide pandemic.) In my thirties, stuck at home, two kids, they go off school in September, I sit down and write a book. Then another. And when neither of those open up the doors to publishing, I start writing something entirely different, abandoning my historical world of Sherlock Holmes and his apprentice—and that third story is the one that sells first.

As may be apparent, I’m not the kind of writer who creates meticulous plans—for a book, or a series, or indeed a life. I’m more the “organic” kind, who finds an interesting seed and plants it to see what will grow.

This does not mean my books aren’t written to a very definite plan. As I’m writing, I can always feel when the story is going the way it’s meant to, and when it’s threatening to veer away. But where other writers work out their plot externally, on a sheet of paper or a white board or PostIts or what-have-you, for a writer like me, the outline lives in the darkest corners of the brain, doled out in bits and pieces as they’re needed. Usually greeted with cries of “Aha!” and “Oh, I see now” and “Hey, what if I then…?”

This… method (may we call it that?) looks haphazard to the outside world—particularly to more deliberate, outline-based writers. To them, it looks as if I’m just spewing a lot of unrelated text onto the page, which I then have to organize into a story. It’s undisciplined. Muddled. Amateur. And though I’ll admit that when I am deep in the throes of a tricky re-write, the second draft where a novel emerges out of a rough 300-page set of notes, it can feel a bit like struggling to bring a riot of anarchists to order. However, even at the most obstinate places, I never really doubt that the back of my head knows exactly where it’s going.

At any rate, that’s my story and I’m sticking with it.

Being an organic/disorganized writer, I’m well accustomed to the world dumping a load of NOPE on any nice, tidy plans I might try and produce. Yes, I had intended to spend the spring in England and France, taking notes and snapshots, figuring out some promising threads of one of my series character’s backstory. I’d even signed a contract more or less saying I would. But: Covid. So I took a step away from the idea, then another, and found myself backing through a whole new door.

Which meant that three weeks into 2021, as a new president was being sworn in, I hit SEND on an email to my editor with an attached proposal and a cover letter that said:

To celebrate the new beginnings taking place on my screen at the moment, here’s my proposal for (working title) Cold Case. The SFPD cold case unit, the house, and the Sixties are the posts it’ll be built around.

Of course, my editor knows me well enough to anticipate that the final product would look nothing like the proposal. And indeed, names, times, victims, situations either shifted or disappeared entirely a few weeks into the first draft. A serial killer appeared and took center stage. A character grew, and others took shape around her. My two time lines began to wrap around each other in some interesting ways.

I finished my first draft, and it was no more clumsy and anarchic than any other. I then set about shaping it into an actual novel, and as I did so, I began to notice some intriguing themes that the back of my head had tossed into the mix.

A few months into the pandemic, as it dawned on us all that we were in for a long haul, writers began to discuss what to do about Covid in their fiction. Anyone writing in a contemporary setting had to struggle with the question: do we incorporate all the details of masks and jabs, hospitals and remote learning, plunging our characters into the madness of eternal lockdowns (or into the sharp terror of a fictional pandemic even more deadly than Covid)? Or do we play it all down, even ignore it entirely? Because it’s one thing to be realistic but honestly, we’re all so sick of it.

A similar conversation sprang up twenty years ago, in the waning months of 2001. It was impossible to write anything but the most serious novel about the 9/11 attack, but it was equally impossible to ignore it. In the end, there was no single answer to the conundrum, but if you talk to writers who were trying to work in the months after that, you will often hear how the event changed what they did. And if you look at the novels published in the following years, you’ll see traces of the Twin Towers even when the actual event goes unmentioned. My own 9/11 novel was not published until 2007 (Touchstone) and is set in the 1920s—but it’s about terrorism, and could not have been written before 9/11.

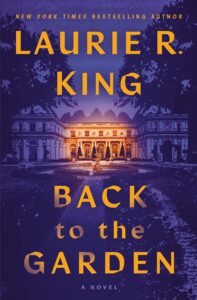

I suspect that in the same way, the pandemic’s drawn-out trauma will take various guises in fiction to come, from outright “suspects all trapped together on an island” whodunits to blithe “I swear it never happened” series entries. My own post-pandemic novel, Back to the Garden, only touches lightly on Covid—for example, mention is made of the estate’s income hit from years of closure—but as I began to look more deeply into its first draft, I saw how much the world of 2021 permeated its every corner. It is set in a house surrounded by high garden walls. Chapters are either “then” or “now,” as if divided by trauma, and both timelines touch on the idea that life used to be, not necessarily better, but freer and more connected: communal, even. Fear of exposure is a common element in crime novels, but here it takes on a note of dread: bones ripped up into the daylight; an unknown serial killer exposed; an agoraphobe hiding behind her walls. Characters include a hermit in the hills, a massively self-absorbed villain, and a woman whose community is almost completely on-screens. The protagonist is, by nature and by recent circumstance, solitary but for a small bubble of companions.

I can’t claim that these themes were premeditated. As I said, I am not a conscious planner, and in any case, any book’s deeper thematic elements can take some teasing into existence. But I think that being kept from travel, being forced inward, amidst a year of tumult and fear and thin rays of hope did bring them up in my writing.

When I began 2021, and one book closed to me, another opened. I was not sure I was ready for it, I knew I might get lost…or I might discover a new world, filled with new people—and find myself launching a new series.

***