Hello, my name is Michelle, and I’m a recovering child-of-a-flower-child.

To be clear, I wasn’t conceived until well after the Summer of Love; in fact, I missed the 1960’s entirely. But my mother watched the happenings in San Francisco from the other side of the country with a longing heart during her teen years, and when she met a man who’d lived in an actual commune in Northern California, she jumped at the chance to come experience first-hand what she’d only viewed from afar. When I was four we made the trek across country and settled in the Bay Area, where, despite the intervening years, the City’s flower-power legacy was still very much alive. My earliest memories include free concerts draped in the mingled scents of patchouli and marijuana, and one of my most cherished childhood belongings was a necklace that declared ‘War is not healthy for children or other living things.’ My impressionable thoughts swirled with the claims that all the world needed was love, and if we would just take care of each other, we could create a paradise on earth. If my pre-teen years had an anthem, it was John Lennon’s ‘Imagine.’

But as I got older, I noticed my mental picture of humanity didn’t match up with what I saw in the real world around me. The principle of own-nothing-share-everything morphed quickly into greed-is-good. The AIDS epidemic swept the area, largely ignored for years by the powers-that-were, and the homeless population grew as mental-health facilities closed. I experienced hungry children and street violence first-hand and learned about horrible, but very human, phenomena like the Holocaust and Jack the Ripper through books. Several high-profile child abductions rocked my community—Michaela Garecht was abducted literally blocks from places where I hung out, and Polly Klaas, abducted and brutally murdered, lived not far from where one of my best friends lived. And when the newspaper published a picture of Leonard Lake, a serial killer who murdered an estimated twenty-five victims, with the one-horned goat ‘unicorn’ he used to lure young women at an area renaissance faire, I felt the gut-punch of realizing I’d crossed paths with him during my family’s yearly visit to that faire. The what-if of that haunts me to this day.

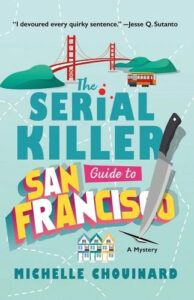

The mismatch between what my parents’ generation had hoped for and the world I saw around me produced many questions and emotions in me, but they boiled down to this: Why? Why was humanity so far from the ideals it claimed to embrace? What made the flower-power ideals so hard to maintain? Why were some people so evil they’d kill another human, or humans? Was it some strange genetic fluke, the situation that person was thrown into, or some combination of both? I dove into true-crime books (and later, podcasts), especially those that featured cases from San Francisco and its environs. Like the main character in The Serial-Killer Guide to San Francisco, I needed to make sense of the motivations behind the dark choices people made. But not because I was consumed with the macabre—because I believed understanding the macabre might help fix it.

And San Francisco’s history, right from its beginnings, gives plenty of opportunity for that understanding. The city was born from an explosion of greed and opportunism: when gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, the population skyrocketed from about 700 to 25,000 in two years, flooded by men scrambling to get rich quick and those ready to take advantage of them. Crime in the early days was so bad the town was known by the nickname ‘The Barbary Coast,’ and wild-west mores (or, arguably, lack thereof) ruled the day. Law enforcement and government structures lagged desperately behind the population swell, and when the town’s merchants had enough of what they perceived as corruption and lawlessness, they formed vigilante committees that eschewed the inconveniences of due process, which was time consuming and sometimes ended with guilty men going free. Thankfully, most San Franciscans didn’t agree that the way to solve the problem was to take the law into their own hands, and they instituted changes in the governing body that directed San Francisco onto a better path.

Several decades and a Ph.D in psychology later I’ve managed to cobble together a tentative understanding of the questions that plague me, and I now realize that ‘fixing it’ means something very different—and infinitely more difficult—than I once hoped. There are both genetic and situational factors that cause people to treat one another unkindly; people’s wants and desires will always conflict, even before you throw psychopathy into the mix. But that doesn’t mean my flower-power idealism is gone—it has just been redirected. Because as I was searching around the dark side of human nature, I realized the beautiful side—like the San Franciscans who wouldn’t allow vigilante committees to continue taking the law into their own hands—inevitably sprung up out of the darkness, even if had to claw and scratch and fight to survive. So while I no longer believe we can build a utopia where we all live in peace, I do believe that once we’re armed with an understanding of the darker side of human nature we know better how to fight against it. We can set up our societies to protect those who are vulnerable, and we can fight for justice for those who have been wronged.

And that’s a philosophy I’ve seen embodied by San Francisco even more strongly than it embodied the Summer of Love. San Francisco has battled for civil rights, the right to organize, LGBTQ+ rights, sex-worker rights, birthed the AIDS quilt, embraced hydroponics to feed the hungry, and so much more. And that’s not because San Francisco turns a blind eye to the dark side of human nature—it’s because since the earliest days of gold-rush lawlessness the City has looked that dark side square in the eye and refused to blink. All are welcome in San Francisco, even if life gets complicated.

No, scratch that.

All are welcome in San Francisco because life gets complicated.

***