It’s a story we know by heart: an older man with a mysterious past owns a luxurious property. The house is so alive it gets its own name. He brings a younger woman home to be his bride. She tries to figure out what dark secret he’s keeping from her. Her life may depend on uncovering it.

From Jane Eyre to Rebecca to The Shining, we love novels about big old houses brimming with secrets, dangerously attractive men, and the women smart enough to survive them.

One literary ancestor of these gothic novels is the seventeenth-century French fairy tale “Bluebeard,” about an aristocrat who forbids his young wife from entering one room in his castle (where he keeps all the corpses of his previous wives)—but her curiosity catalyzes her to disobey him.

Four years ago, when I decided to write a contemporary gothic novel in the lineage of Rebecca, I knew what I had to do. I had to murder someone in my imagination. For my friends who are mystery and thriller writers, this is one of the perks of the job; on vacation, they’re looking for the perfect spot to bury a body; when a shocking crime goes viral online, they’re memorizing the murder weapon.

If I wanted my novel to sell, my victim was a given: a young white woman, on the verge of becoming who she was meant to be. Laura Palmer: Homecoming Queen. I could get creative with the motives and methods of my murderer, and the core wounds of my curious protagonist, but I knew my reader was expecting a dead white girl on-demand.

In her essay “Toward a Theory of a Dead Girl Show,” Alice Bolin argues that TV shows like Twin Peaks, Pretty Little Liars, Top of the Lake, and True Detective “help us to work out our complicated feelings about the privileged status of white women in our culture.” The “perfect” white female victim erases “the deaths of leagues of nonwhite or poor or ugly or disabled or immigrant or drug-addicted or gay or trans victims, encapsulates the combination of worshipful covetousness and violent rage that drives the Dead Girl Show.”

In her list of identity markers, Bolin forgets one: “old.”

Our fictional victims are perfect because they expired when they were ripe. They died at the cusp of becoming. We can’t blame them for their fates—they didn’t live long enough to make choices they’d later regret. The perfect victim is the one who’s never harmed anyone else. She can’t be the subject of harm—only its object.

We’re just as ambivalent about young women as we are about white women—we revere young women, we fear them, we judge them, we scold them, we seek their approval. Look at the cultural meatgrinder we put Lena Dunham through in her twenties. Look at the online hate directed at Rachel Zegler every time she stops singing and voices an opinion.

Dead girls get preserved before they can become problematic women.

But I couldn’t bring myself to kill a young white woman in my head for my art. Women are the largest consumers of true crime books and podcasts; our fear of being victimized by men makes us vigilant students of this gruesome genre. Perhaps surviving an abusive relationship as a young woman has made me want to avoid imagining an outcome where I didn’t. I also would have felt like a hypocrite exploring my mixed feelings about turning dead women into entertainment through the vehicle of a murder mystery. Ultimately, I decided not to add to the dead girl canon.

What if instead I wrote a gothic novel that explored another existential threat to women—the fear of aging and irrelevance? Of invisibility? Of career death?

A great irony for women artists is that if you want your work to become immortal, it helps to have an untimely death.

Think of all the women artists we remember because of how their lives tragically ended: Sylvia Plath and Francesca Woodman, Brittany Murphy and Amy Winehouse, Selena and Ana Mendieta. It’s impossible to engage with their work without their death floating above it like a veil.

This can instill a dark envy in living artists who wish for more recognition. The Russian poet Vera Pavlova has a poem that begins, “A cake of soap, a length of rope,” alluding to Plath’s “Lady Lazarus,” and ends: “Too late for me / to have died young.”

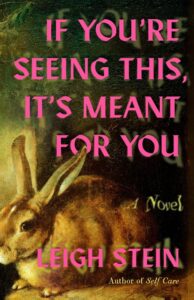

In my novel If You’re Seeing This, It’s Meant for You, a childless thirty-nine-year-old woman who is aging out of the media industry has to get up close and personal with the generation coming to replace her, when she takes a job managing a hype house of Gen Z content creators, set in a crumbling Hollywood mansion. One of the young content creators gained a cultish following for her eerily accurate tarot card readings—then she mysteriously disappeared from the house.

A disappearance allowed me to explore how once you’ve achieved relevance on the internet, by building an audience, you can never be forgotten—even if you want to be.

Britney Spears once said, “There’s only two types of people in the world: the ones that entertain, and the ones that observe.” But fans today are more than observers—on subreddits and in TikTok comment sections, they’re participants. Fans are creators. The journalist Fortesa Latifi covered a story earlier this year of a momfluencer who lost a toddler in a tragic accident; other creators on TikTok immediately centered themselves in the story, by posting videos of themselves crying, or sharing screenshots from the medical examiner’s report, or spreading unsubstantiated rumors about the mother’s negligence, shaming her for the death of her own child.

In my novel, the millennial, a former photographer and longtime Francesca Woodman fan, realizes that the key to saving herself from the threat of career irrelevance is to leverage the cultish devotion of the tarot card reader’s fans, and invite them to participate in a brand campaign that doubles as a search for the missing influencer.

Once my novel went on submission, the first rejection I received was from an editor who was hoping for a murder. When I had a phone call with the editor who would ultimately acquire the book, I confessed at the end that I was worried going into the call that he was going to tell me I had to murder my tarot card reader.

“I would never tell you to do that,” he said. “It’s your book.”

I tried to write a gothic mystery that implicates us all in our appetite for stories of women who become more interesting once they’re no longer here.

***