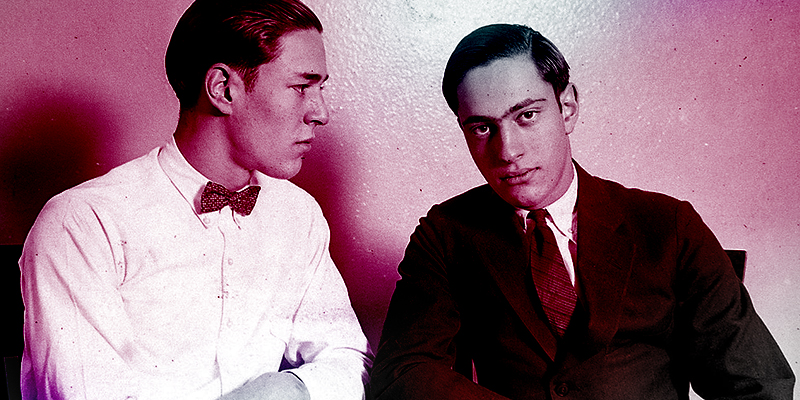

“What a rotten writer of detective stories Life is!” By the time he wrote these words, Nathan Leopold, Jr. was middle-aged and balding. But in the American consciousness, he was forever immortalized as the sullen teenager he had been in the sweltering Chicago summer of 1924, infamously linked—in name and in deed—with his partner in crime, Richard Loeb.

Leopold and Loeb were nineteen and eighteen respectively when they committed the “crime of the century.” On May 21, the two boys, driving a blue Willys-Knight rented under a pseudonym, picked up fourteen-year-old Bobby Franks as he walked home from school. They had planned carefully for months, orchestrating what they thought would be the perfect crime. They would kidnap a young boy and get a ransom payment from his father, but to be certain they couldn’t be identified as the abductors, they would kill the boy, too.

The victim was chosen at random. Bobby happened to be walking alone that day, just a few blocks from home. Loeb knew the Franks family was wealthy—certainly Mr. Franks would pay the $10,000 ransom demand. Once Bobby was in the car, either Leopold or Loeb bludgeoned him with the blunt end of a chisel (each pointed a finger at the other during their otherwise corroboratory confessions, although evidence suggests it was Loeb who attacked, while Leopold drove) before gagging the young boy with a cloth in the back seat of the vehicle, where he suffocated to death.

With the body in the car, Leopold and Loeb stopped to pick up two hotdogs and two bottles of root beer. After nightfall, the pair stripped off the boy’s clothes, poured acid on his face and genitals in an effort to conceal his identity, and left Bobby Franks’ body hidden in a remote spot Leopold knew of from bird-watching trips. Unbeknownst to either of them, Leopold’s eyeglasses slipped from his jacket pocket, landing near the body.

Loeb phoned the Franks household to inform the boy’s mother that her son had been kidnapped and a ransom note would soon follow. The letter arrived the next morning, but shortly thereafter, their plan was foiled when the body was discovered alongside a pair of eyeglasses which the Franks family confirmed did not belong to Bobby. A unique hinge on the frames allowed the police to match them to Nathan Leopold, whose alibi quickly crumbled. At four o’clock in the morning on May 31, 1924 both Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold confessed separately to the murder of Bobby Franks.

“The Franks murder mystery has been solved,” State’s Attorney Robert Crowe announced to a dozen reporters who had waited overnight for a break in the case. Leopold and Loeb instantly became household names, as the case garnered national media attention. Who was no longer the mystery in the Franks murder case. The question then, and still today, was why?

In the ten days between the murder and the confessions, there had been much speculation about the murder of Bobby Franks. The body had been found naked, so it was widely assumed that the crime had been sexually motivated. The day the boys confessed, the Chicago Tribune published a censored version of a letter Leopold had written to Loeb after a fight, which insinuated that their relationship had been sexual. The coverage of the case captured the spirit of the Roaring Twenties with all its talk of sex, money, and violence.

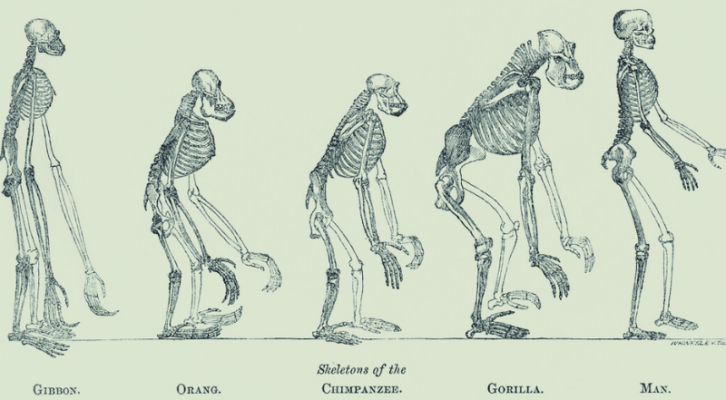

The famed Clarence Darrow, who the following year would serve as the defense in the Scopes Monkey Trial, pleaded the boys guilty to avoid a jury trial, which he believed would result in a death sentence. Using testimony from forensic psychiatrists (which was not yet standard practice in the courtroom) Darrow did not argue that Leopold and Loeb were insane, but that certain mental “abnormalities” were mitigating factors in their guilt. The judge ultimately ruled that the boys were too young to be executed and sentenced each to life in prison for the murder and an additional ninety-nine years for the kidnapping of Bobby Franks.

The nation watched as the courtroom drama unfolded. A litany of explanations for the crime covered front pages of newspapers across the country, spinning into a web of competing and often contradictory narratives and laying bare the cultural anxieties that plagued Americans in 1924. It was a lack of parental supervision, some claimed, as more and more women left the home and entered the workforce. Or perhaps it was the extravagant wealth of both the Leopold and Loeb families, or alcohol, or “overeducation.”

Leopold and Loeb were indeed both well-educated—at the time of the crime, both had already completed their undergraduate studies. At fifteen, Loeb was the youngest graduate of the University of Michigan. Leopold was a respected amateur ornithologist studying law at the University of Chicago, with plans to attend Harvard in the fall.

As the dominant narrative of the pair took shape in the press, reporters zeroed in on Leopold’s fascination with the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. In Leopold’s eyes, Loeb embodied the Nietzschean concept of the Übermensch, or superman, which, according to Leopold, meant that he was “exempted from the ordinary laws which govern ordinary men.” This complemented Loeb’s long-held desire to become a master criminal who would commit the “perfect crime”—a fantasy borne from his love for crime fiction and detective stories.

In their report for the defense, the psychiatrists wrote that Loeb experienced an “abnormal mixing of phantasy with real life.” But if Richard Loeb had trouble distinguishing reality from crime fiction, then so did the rest of America—then and now.

if Richard Loeb had trouble distinguishing reality from crime fiction, then so did the rest of America—then and now.The lines between truth and legend in the Leopold and Loeb case were blurred from the very start. In the days following the confession, the press latched onto one quote that ostensibly addressed the motive. “It was just an experiment,” the June 2 edition of the Chicago Tribune quoted Leopold as stating, “It is as easy for us to justify that experiment as it is to justify an entomologist in impaling a beetle on a pin.” This was damning evidence of the two cold-blooded killers’ callousness.

But in his autobiography, Life Plus 99 Years (1958), Leopold maintained what he had also claimed in 1924—that his words had been misconstrued by the reporters. “What I said was, ‘I suppose you can justify this as easily as an entomologist can justify sticking a bug on a pin. Or a bacteriologist putting a microbe under his microscope.’” He wasn’t the scientist, and he wasn’t experimenting. Under a barrage of questioning from the reporters, he was their specimen. “I was being sarcastic,” he wrote, “I was telling them that they were showing me, a human being—and a human being in a tough spot—no more consideration than a scientist showed an insect or a microbe.”

Reporters were eager to portray Leopold and Loeb as self-aware, evil thrill-killers who didn’t just fail to comprehend the value of human life, but actively rejected that value. It’s a tempting portrait; Leopold was, by all accounts, a smug and haughty teenager. But this narrative is so seductive in part because it is so reductive.

Leopold’s motive, as he recalled it in his autobiography, was far more banal. “My motive,” he wrote, “so far as I can be said to have had one, was to please Dick. Just that—incredible as it sounds. I thought so much of the guy that I was willing to do anything—even commit murder—if he wanted it bad enough.”

“How,” Leopold asked, “Can anyone hope to enumerate the components in human motivation in real life? Isn’t it only in fiction that jealousy, or revenge, or hatred, or greed is found, simple and unadulterated, as the wellspring of human action?”

In contrast to the fictional motivations that drive the tidy narrative arcs of detective stories, real life motives are messy and often deeply unsatisfying—the kind that would be totally unconvincing in a work of fiction. Real motives—like real people—often don’t make sense. But clear-cut motives, however manufactured, can help us to make sense of otherwise senseless acts of violence, like the murder of Bobby Franks. If, rather than foolish, immature teenagers, the perpetrators were conscious evil-doers who saw themselves as unconstrained by the moral standards of ordinary humans, then any punishment was justified.

Scholar Mark Seltzer has described the true crime genre as “crime fact that looks like crime fiction.” As such, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1966) is often credited as the first modern true crime text. The book purports to depict, as its subtitle suggests, “a true account of a multiple murder and its consequences.” Capote himself claimed that he had invented a new literary genre—the nonfiction novel, “a narrative form that employed all the techniques of fictional art but was nevertheless immaculately factual.”

Later that year in a piece for Esquire, Phillip K. Tompkins noted numerous inaccuracies in In Cold Blood, including significant discrepancies between dialogue and transcript records and a concluding scene that was entirely fabricated. Capote had molded the real people he wrote about into literary characters, grafting the true story of murder onto the prescriptive narrative structure of detective novels.

Fiction has thus, paradoxically, become baked into modern true crime. In Cold Blood undoubtedly played an important role in shaping the genre, but Capote’s work—despite his assertions that he had conceived of a new literary form—built heavily on conventions developed by earlier writers, including Meyer Levin’s 1956 novel Compulsion.

A former classmate of Leopold and Loeb, Levin was a budding journalist in 1924 and a strong advocate for Leopold’s parole in the 1950s. Compulsion was his heavily researched interpretation of the case, which he referred to in the foreword as a “contemporary historical novel or a documentary novel.” Capote scathingly critiqued Compulsion as “a fictional novel suggested by fact, but in no way bound to it.” Unlike Capote, Levin never claimed that it was. Levin changed the names of the characters and noted explicitly that “some scenes are … total interpolations, and some of my personages have no correspondence to persons in the case in question.”

Capote tends to get a lot of credit for shaping the modern true-crime genre, but the case of Leopold and Loeb has made considerable contributions to the genre as well—and not just in the form of the many pop culture depictions of the case, from Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) to the twenty-first century musical rendition, Thrill Me: The Leopold and Loeb Story (2003). Beyond this preponderance of portrayals of the case, representations of Leopold and Loeb also helped to popularize the generic convention of adopting fictional techniques to tell a true story—or at least, one that purports to be.

[R]epresentations of Leopold and Loeb also helped to popularize the generic convention of adopting fictional techniques to tell a true story…The preface of Simon Baatz’s For the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder that Shocked Chicago (2008), the most popular book on the case, begins with the words “This is a true story.”

The book’s opening scene in the Franks household depicts the family sitting down for dinner, awaiting the arrival of Bobby, who will never come home. As Erik Rebain, author of Arrested Adolescence: The Secret Life of Nathan Leopold, has pointed out, “From a narrative standpoint it makes perfect sense to start the book with this scene … yet this dinner scene is completely fictional.” Though Baatz is a historian, these fabricated scenes appear throughout the book, and in so doing contribute to, rather than circumvent, the mythologizing of Leopold and Loeb.

A more recent retelling of the case, Nothing But the Night: Leopold and Loeb and the Truth behind the Murder that Shocked 1920’s America (2018) by Greg King and Penny Wilson attempts a revisionist approach. King and Wilson refute the accepted narrative of Richard Loeb as the instigator and turn it on its head, presenting Leopold— on the basis of very little evidence—as a volatile and dominant serial killer in the making. The authors are careful to hedge, making it clear that much of their analysis is speculative, but the book’s subtitle implies more than mere conjecture. In crime fiction, when the audience knows the identity of the killer from the start, this sort of plot twist works well (think Psycho). But real cases rarely lend themselves well to such tropes.

A century after their crime, the story of Nathan Leopold’s and Richard Loeb’s crime has assumed the status of American folklore. The story, with its larger than life characters and salacious details, has many of the features that make for compelling true crime narratives, in part because our understanding of violent crime is so often heavily mediated through crime fiction. The many representations of Leopold and Loeb demonstrate the pitfalls of narrativizing violent crime in ways that mirror fiction; flattening real people into a cast of familiar character archetypes collapses the complex realities of violent crime in favor of a digestible narrative.