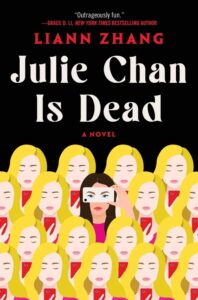

In Liann Zhang’s debut thriller, Julie Chan is Dead, an impulsive identity swap unleashes dark secrets and plenty of trouble, against the backdrop of social media influencing.

Separated at a young age, identical twins Julie Chan and Chloe VanHuusen grow up to live disparate lives: Julie scraping by as a supermarket cashier dominated by her abusive aunt, Chloe thriving as a beauty influencer after being raised by wealthy adoptive parents. After Chloe mysteriously contacts her, Julie discovers her twin’s dead body and, with nothing to lose, decides to assume her identity. But Julie soon discovers that the life of her online-darling sister was anything but picture-perfect. Problems abound and soon spiral out of control to threaten her own life.

Fast-paced and bitingly funny, Julie Chan Is Dead skewers our online habits, power structures, and even gender roles, while exploring themes of authenticity, grief, and belonging.

Liann Zhang is a second-generation Chinese Canadian with a degree in psychology and criminology and some insightful experiences as a social media content creator. She splits her time between Vancouver, British Columbia and Toronto, Ontario.

I connected with the author over Zoom to discuss her sharp debut. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Jenny Bartoy: I would love to know how you came up with the idea for this novel.

Liann Zhang: I feel like there was so much going in my head, but a lot of it was inspired by my own time as a skincare influencer back when I was a teenager. I got to see behind the scenes and experience the dynamics of the different people [in that world]. But also just being a teenager and a child that’s always been chronically online, I’ve seen every single piece of drama and internet scandal that someone could consume. And there’s just so much content there that I knew I needed to put it into a book. Once I found out how to frame the story, it kind of just went from there.

JB: Twins are at the center of this novel. Twins have always fascinated us culturally, and there seems to be a resurgence in recent years. What appealed to you about the mystique of twins for this story?

LZ: Originally, the identity swap came from another novel that I wrote, a fantasy book, but it never went anywhere. But in terms of the twins, I studied psychology at university, and there were studies following twins that had been separated—which would be kind of an unethical study these days, you don’t really see that anymore—and they were trying to determine nature versus nurture, that type of thing. And that always fascinated me. For this story, I really wanted to be with the character that’s kind of thrust into this [different] world. You don’t see her slow growth, you’re right in the middle of it with her. And what a better way than to do a little twin swap? That’s just a fun way to throw the character right into the middle of everything.

JB: It feels like a clever play on the “evil twin” trope from soap operas, but that allows for exploration of significant, deeper themes. One of the big ones is the nature versus nurture theme that you mentioned. Specifically this book examines the haves versus the have-nots and the power of money and privilege in deciding who sets the narrative. Why did that interest you and how does social media play into this?

LZ: This came up very naturally while I was writing, just because it was something that I [experienced] personally. While I was in the influencer scene, it wasn’t based on personality, it wasn’t because I was funny or charismatic — I was in the skincare world. So in order to review and take pictures of skincare, you had to own items. You couldn’t just own one Neutrogena face wash and make a blog out of it. You needed to have several items, which of course cost money, which in itself is a privilege. When I was coming up and entering these group chats, I noticed that a lot of these people were very privileged people who already owned a lot and continued to get a lot. I counted myself lucky too, because my mom was very supportive. I also had a part time job, and I lived at home, so it’s not like I had expenses. I just went to Sephora and bought stuff with my bakery money I earned. But a lot of people aren’t able to do that, and you do see a concentration of privilege within these influencer communities, specifically beauty and the type of niches that require you to have items. So that theme came up very naturally.

JB: You touch upon the question of authenticity quite a bit. What is authentic? I feel like that’s the real mystery that your book strives to answer.

LZ: I often see big words [like “authenticity”] floating around the influencer space. But as more people become influencers, and more time has passed in the context of this influencer world, we’re starting to discover that a lot of them are not who they are [online]. And you even get major news stories about influencers being awful behind the screen. Personally, I have the belief that these social media platforms, and the big techno feudalistic overlords that control everything, like Google and Meta, really do not care about authenticity and real connection. They just want to scale their data and get ad revenue. So really, these platforms are there for entertainment, and there’s a lot you can try to be authentic, but at the end of the day, you can only show so much of yourself online, and anything you do show is something you actively curate, [for] an audience watching. And when you consider an audience, how authentic is it really? These days, I treat social media as kind of a new age reality TV show. I don’t even want to try to believe that these people are being real, I’m just going to consume them [as entertainment.]

JB: Your novel is part of an exciting trend that I like to describe as “flipping the narrative on villainy”—subverting the dominant sociopolitical (ahem, white and patriarchal) narrative that likes to point the finger at minorities, people of color, people who are poor or marginalized in any way, as the “villain” for pretty much anything. In our current times especially, what do you think is the power of writers, specifically in fiction, to change those deeply ingrained — and problematic — narratives?

LZ: We’re seeing more and more stories pop up by different types of authors who are not the traditional white male, or female even, writers. More and more we’re getting [perspectives] that acknowledge the power dynamic that’s there and provide an outside viewpoint. And I think reading is one of those ways that you can truly empathize with a different position, because you’re literally reading from their point of view and putting yourself in their shoes. Fiction is an avenue toward understanding that feels a little bit less preachy, or [less boring than] like, reading a news report. It forces people to acknowledge what’s going on, but in a fun, entertaining way where it’s not like you’re reading a textbook. Fiction is a fun way to engage with those types of [challenging] ideas.

JB: Throughout the novel, you call out how rigged and riddled with problems a lot of our systems are — the police and its issues with mental illness, the judicial system, etc. Why was it important for you to write about this?

LZ: I did study psychology and was on the track to go into my master’s, and part of that was gaining work experience. So for two or three years, I worked at a suicide crisis line, and I did see a lot of these types of stories that Julie goes through in the book, where people who are having a really tough time get the police called on them or EMTs, and it is not a positive experience at all. And it gets to the point where we become scared to call them, even though it’s kind of the only resource, because on a crisis line, how much can I really do from miles away? That was something that was top of mind for me, because I was still working there while I was writing this book. It felt very important to acknowledge that resources exist, but they do not work as they’re supposed to, and a lot needs to be fixed.

JB: This book is a wild ride—funny, poignant, fast-paced, unabashedly political, and at its heart is a mystery—but I’m not sure I would categorize it as a “mystery” per se. I would love to know your intentions in terms of what you were writing. Did you want to write a murder mystery?

LZ: What you’re verbalizing was very much like my own brain, especially when I was querying agents. At the time I was like, what is this really? Is it a thriller, or is it mystery, or is it horror? I feel like there’s so many things that it could be categorized as. I did end up going with thriller, just because I feel like it was a safe catch-all and one of the better selling, more commercial genres that would guarantee me some kind of success, hopefully. And I feel like in any thriller, there’s always mystery. It’s so deeply intertwined that you can’t really have one without the other.

JB: This story feels satirical and critical of the beauty influencer world, but also a little bit like a love letter to it. I feel like I could definitely sense both. Would you agree?

LZ: Yeah. I myself have a huge love-hate relationship with the internet and with influencers. Because, on one hand, I can recognize the awful things that it’s doing to society, to my mind, to the people that I know. I can very clearly recognize this and put it into words, and yet I don’t see a future where I’m going to give up my social media. I’m stuck to it, and I’m addicted. And not only that, it’s not even a negative addiction. I’m getting a lot of joy from it, even though it’s probably not doing great things to me in the end.

But [the book] does reflect my brief time as an influencer, what I kind of went through on a small scale. What Julie does, where she’s receiving all these free things and getting paid for a picture — it’s such a novelty. When I was in high school and working part-time at a bakery, I would post one photo and it would [earn] more than I made that whole month. And I got to connect with lots of interesting people and lots of brands. But eventually I started to get bored of it. I started to look at, oh my God, all these things I’m receiving, it’s just piling up, it’s turning into garbage. Like, I have one face, how am I supposed to use all these things? And then I would recognize the messaging of these brands that claim to be eco friendly and they’re sending you giant boxes full of packing peanuts and styrofoam. And it was one of those moments where I [thought], okay, everybody is lying, nothing is real.

I got sick of that whole world along with posting on social media. It’s so nice getting a lot of likes on a post. It is an endorphin rush—it’s a great feeling. But then this one post got 1000 likes, and the next one gets 200, and then you’re stuck there figuring out what happened between this and that, and it becomes this awful, agonizing feeling that just grows and grows. At the end of the day, I hate everything about it, but at the same time, I can never put it away. It’s like a toxic relationship.

JB: The theme of family is at the forefront of this story, and it’s interesting how social media provides this sort of parallel to the dynamics of family that Julie and Chloe experience. There’s your biological family, your adoptive family, and then your chosen family, each of whom might be wonderful or completely toxic. You explore all those layers in the book. Was that parallel organic or intentional?

LZ: It was very purposeful. I don’t know if you watch a lot of these bloggers or influencers, but they’re always calling their fans their family. Like, you guys are my family; I love you guys; thank you so much for supporting me. It’s a rhetoric that a lot of influencers use, and I think I fall for it too. Sometimes I get really attached to these people, because I feel like I know them. They show me so much, but also nothing at all. And in a way, it does feel like you’re part of the family. Sometimes you watch these people grow up from children to full grown adults, and you feel like you’re there on the journey, like they’re your friend. So that does play into that online family dynamic. But also, I feel like a lot of people my age have found genuine friends online.

JB: We talked earlier about authenticity and what that really means when, by default, what you’re doing online is not really authentic, but social media has sort of co-opted that term. You write about this quite a bit: has it really happened if you’re not posting about it, and on the flip side, is it made real if you create content about it? Can you manufacture your reality simply by posting and putting it out in the world?

LZ: Yeah, that question, “Did it really happen if you didn’t post it?” I think a lot of people these days don’t think so. I’m seeing people every day posting every meal—the camera eats first, as they say. Every time they go on a walk, they have to post. [And this question of reality and authenticity] is definitely one of the central themes of the book. The main character, in itself, is kind of an exaggerated example of that. She literally looks identical to the person she says she is, but she’s an entirely other person, which in a way could potentially be every influencer—they look like this, but who knows, behind the screen, who are they really? That’s kind of the question that I’m posing. I feel like the whole story in itself is a characterization of online culture and how we all want to be something. We’re so desperate to cling on to this thing, metaphorically, that we will do anything. We’ll lose parts of ourselves to attain that, even though, like, what are we even trying to attain?

***