Gabriel Dax, the main character of William Boyd’s terrific new novel, is a talented journalist and the author of several acclaimed travel books—”a clever bugger,” as an admirer puts it, but heretofore not a figure of intrigue. In “Gabriel’s Moon,” he becomes one. The action starts in the early 1960s, when Gabriel, a Brit who suspects his brother has ties to the country’s intelligence services, is recruited to travel to Spain, pick up an artwork and deliver it to a person he’s never met. It’s the height of the Cold War, and our man in London has become an international spy.

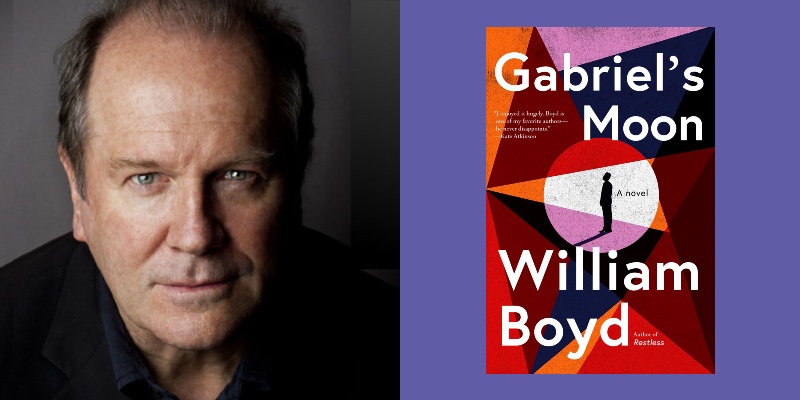

Unlike his protagonist, Boyd has been here before. An Englishman raised in Ghana and Nigeria, he frequently writes about Brits who find trouble overseas. In his debut, A Good Man in Africa, a mistake-prone British diplomat is stuck in a series of comic entanglements; Sean Connery costarred in a film adaptation. Boyd is also the author of the spy novel Restless, which became a BBC miniseries, and Solo, a James Bond novel authorized by Ian Fleming’s estate. Speaking from his home in London, where he’s working on a second Gabriel Dax book, Boyd talked about staging a literary hoax with David Bowie, summoning the mental discipline to write novels and discovering that spy stories contain deep human truths.

I think I’m reaching you in London. When a film crew visited you there in 2017, you estimated that you had 10,000 books. What’s the total these days?

Well, they’re dispersed between two houses, our house in France and our house here. I suspect it’s gone up by at least 2,000. I’m trying to institute a purge. I’ve bought so many of the books to research my novels, and once the novel is written, I’m never going to go back to, say, turnpike roads in the north of England in the 19th century.

All the way back to A Good Man in Africa (1981), you’ve had a soft spot for Brits who are out of their depth abroad. Does this have something to do with your growing up in Africa?

I think we’re all a bit out of our depth, aren’t we? Aren’t we all a bit flawed, insecure? My characters are not classical heroes; they’re human beings with everything that that implies, and I tend to put them in situations where they’re tested. Will they come through, or will they succumb?

Gabriel, for sure, is most interesting when he’s unsettled and scrambling a bit.

It’s a kind of truth about narrative. Things have to go wrong. If they don’t go wrong, it’s not interesting. It’s that old line from Henry de Montherlant: Happiness writes white on the page. There has to be something that’s unfamiliar or challenging. It is almost a requirement of a story. Gabriel is a classic example of a reluctant spy. He never wanted to be thrust into this world of Cold War espionage. But he finds he has a kind of talent for it. I look back at all my novels—the character is tested and things go wrong.

Your book mentions some notorious British spies of the era, a few of the Cambridge Five, but not Kim Philby. There’s a character in your novel, Kit Caldwell, who has some similar traits—charming, louche, Soviet friends. Is he based on Philby?

Yes, absolutely. I’m sort of obsessed with Philby. He’s an extraordinary example in the world of espionage. For 23 years, he was a double agent for the Soviets in the UK. Very few people can survive that sort of pressure. When I wrote my novel Restless, my first spy novel, I imagined a character who hadn’t defected and was somewhat based on a person you may have heard of, Anthony Blunt.

He was the art historian?

Yes. He was the head of the Courtauld Institute at the University of London. He was knighted. He was the keeper of the Queen’s pictures. You couldn’t get a more establishment figure. And yet he had been a Soviet double agent in the ‘30s and ‘40s. They’re deeply intriguing to us Brits, these bourgeois traitors that we seem to engender. Philby, in many ways, is the most fascinating. The others became drunks or they cracked up. But Philby hung in there. You can see it on YouTube, Philby defending himself with this suave aplomb.

You like having some fun with the spy genre’s tropes. I’m thinking of Gabriel’s trip to acquire a weapon, which is kind of unglamorous and embarrassing for him—he’s offered a small semiautomatic known back then as a “lady gun.” This isn’t exactly James Bond and Q chatting about state-of-the-art gadgets.

You’re absolutely right. It’s taking the expectations of the genre and turning them on their head, or subverting them, and having a bit of fun with them. In our literature and to a certain extent in American literature, many serious novelists have written spy novels. It goes back to Joseph Conrad in 1907.

The Secret Agent.

And after that, there are dozens: Graham Greene, Somerset Maugham, John Buchan, Elizabeth Bowen, Muriel Spark. And then my contemporaries, Sebastian Faulks, John Banville. Why do we write spy novels? This is my theory: I feel that the world of espionage is actually the human condition writ large. We’ve all betrayed people. We’ve all lied to people. We’ve all changed our identity to gain something, for a minute or two or a week or so.

We understand instinctively what a spy does, though the stakes are so much higher for them than they are for us. I think that’s why of all the genres that are available—from horror to sci-fi, romance, crime, cozy crime—serious novelists have been attracted to the spy novel.

In one scene, a character shares some sensitive information with Gabriel on the promise that he keep it secret. Gabriel says something like, Who am I going to tell? I’m a travel writer. I was happy we were in the 1960s, and he couldn’t text somebody about this, or post it on social media. From your perspective, is there something attractive about setting a novel before the internet?

Massively attractive, particularly with the spy novel. It’s the analog world. If you wanted to make a phone call, you had to find a phone box. It took a while to travel and to make appointments. Today’s spying is basically electronic surveillance. The agent in the field is far more interesting.

There’s a great recurring bit about Gabriel’s failed attempts to catch the mice that are running around his apartment. It works comically and metaphorically. What can you tell me about that mini-storyline?

As I say in the novel, the war between mice and men is never ending. As I was writing the novel, I was trying to solve a rodent problem here in London.

So you finally confess—you are an autobiographical novelist!

It’s autobiographical, but it’s also symbolic because in a way Gabriel is kind of mouse figure—people are trying to trap him or get him under control.

At end of the novel, there’s a list of Gabriel’s books. These are made-up titles, of course. This reminded me of Nat Tate. For readers who don’t know about this, can you give me an abridged version?

It was 1998, so it’s pre-Google. It wouldn’t have worked today. I was working on a very serious art magazine. I was on the editorial board, and I joined the board at the same time as one David Bowie.

The editor of the magazine said, How do we get fiction into a serious art magazine? I said, Why don’t I invent a painter? So I did: Nat Tate, an American expressionist, 1928-1960. Destroyed most of his work before he committed suicide. And then Bowie said, Why don’t we publish it as a little book? We produced this wonderful monograph, which has all the trappings—acknowledgements, notes and so on. I got real people to remember Nat Tate. You’re reading this book skeptically, but then you come across Gore Vidal saying, Nat was a good looking boy, but he drank too much. The reader thinks maybe this did happen.

But you didn’t stop there.

We decided to have a launch party in Manhattan in Jeff Koons’s studio. Bowie read from the book deadpan. And a British journalist who was one of our conspirators was there asking people if they’d heard of Nat Tate. And, of course, people being people said, Yeah, it was a terrible tragedy that he died so young.

Oh no! You must lie in that situation.

You must lie. We were going to do exactly the same in London a week later, but the journalist who had asked the leading questions couldn’t sit on the story any longer. It became a 24-hour news event. I was interviewed around the world.

It sounds like you’re cool under pressure. Are you like Gabriel, who can write even as lots of stressful stuff is going on in his life?

Totally able to do that. I can flip a switch in my brain, if you like. I think that’s because in my early writing life, when I was at Oxford, I did all my writing in libraries—quiet places, but people are wandering around, there are distractions. I got used to switching on, switching off. Today I can sit in public and write, whereas I have friends who have to rent a cottage in a pine forest 10 miles from the nearest village in order to concentrate.

You mentioned Graham Greene. Famously, he wouldn’t quit work for the day until he hit his word count. Do you have rules like this?

I can write fiction for about three hours a day, and then I correct and think about the next day. I write usually between lunch and cocktail hour. I can write 1,000 words or 1,500 words or 800 words. But you have to do that every day, seven days a week. That’s how novels get written.