While we all romanticize the notion of a writer engrossed in their craft solely to satisfy their creative impulses, seasoned authors understand that a pivotal moment arrives when their book is slated for publication. This critical juncture heralds judgment in the form of reviews and sales. Esteemed critics associated with publications like The New York Times Book Review or The New Yorker may voice their opinions. The question looms: even if reviewers laud a book, will it translate to sales? Will there be sufficient reader engagement to propel purchases? This juncture often presents a dichotomy for writers, torn between crafting literary fiction to appease discerning critics or embracing genre conventions in a bid to attract a broader readership.

What is literary fiction anyway? It is often considered a more complex form of storytelling, with an emphasis on the complexity of characters, exploration of the human condition and beautiful language. It tends to emphasize prose, style and artistic expression, delving into the psychological makeup of characters, utilizing innovative narrative techniques and exploring complex themes, symbolism and allegory.

On the other hand, genre fiction often focuses on more plot-driven narratives and upholds particular conventions, themes and settings. Some mainstays of crime fiction, for example, may include red herrings, the murder of an innocent, a detective and a denouement. The primary goal of genre fiction may be to entertain readers within a well-defined framework of expectations, using familiar tropes and conventions.

However, in recent years, the blurring of the traditional boundaries between literary and genre fiction has become an emerging trend. Contemporary authors are pushing boundaries and creating an amalgamation of literary and genre elements. Crime writers can sometimes feel like they are caught between literary and thriller audiences, with the literary folks complaining about too much melodrama and the more hard-core thriller fans wanting faster pacing and more twists.

I reached out to some top writers to discover their thoughts on this complex issue:

Ruth Ware (Zero Days)

My approach has always been to try to shut out the expectations as far as possible while I’m writing, and write the book I personally would want to read. I find that if I think too hard about what I’m doing and start imagining all the potential reader complaints, it can paralyse me. It’s when I’m editing that I allow the more critical, analytical side of my brain to click into work, and I try to look at the book critically and ask myself if I’ve given my readers enough reason to turn the page each time.

Jean Hanff Korelitz (The Latecomer)

The key to toeing the literary/thriller line is to be wilfully obtuse about where it is. At the same time, we selfishly write to our own preferences: good writing and good storytelling that will not fail to surprise us. (And yes, I mean “us” as in ourselves, the actual writers, because when this writing thing goes well we’re the first ones experiencing those plot twists as twists.) The wonderful discovery is that there are so many of us out there: readers who want to be truly surprised by a plot and who don’t want writing that’s dumbed down or just plain bad.

Paula Hawkins (A Slow Fire Burning)

I don’t try to tailor my writing to a specific readership. I do understand that readers of crime novels will come to my books with certain expectations (a body, blood on the carpet, a mystery to be solved), but those aside, I would never be able to finish a novel if I spent too much time thinking about what a reader might want. As a novelist, there is so much else that demands your attention: character and plot, structure and voice. I think that if you focus on those aspects of your work, your creative experience is more rewarding, and you’ll write a much better book.

Wendy Walker (American Girl)

To me, literary fiction is a more intellectual experience. Thrillers are more emotional. And by emotional, that could be a breathless, urgent experience. Or a connection with the past or present trauma that the characters are experiencing. But at the end of the day, it is about emotion. If you can blend an emotional experience with an intellectual one, to me, that is the perfect reading experience.

Lan Samantha Chang (The Family Chao)

Some novels known as the greatest works of literature are crime novels, and some crime novels are great works of literature.

Lynne (Liv) Constantine (The Senator’s Wife)

When I craft a story, I don’t think about where it falls on the literary/thriller line. My goal is to bring fully formed and flawed characters to life who are struggling with the same questions and issues of the human condition that face us all. I want my readers to care and root for my character while I keep them on the edge of their seats hoping and worrying about things turning out okay.

Chris Pavone (Two Nights in Lisbon)

The category distinction is a serious concern for publishers and booksellers, but I don’t think readers wring their hands too much about it. People are just looking for good books to read. Although everyone has a different idea of what constitutes a good book, I trust that there are enough readers who are looking for the same types of books that I like to read, and these are the types of books that I write.

Nancy Jooyoun Kim (What We Kept to Ourselves)

I consider myself to be polygenre—which I’ll coin right here! In my books, What We Kept to Ourselves and The Last Story of Mina Lee, genre is an extension of character and theme. I choose the vehicle (the structure and plot) after I’ve figured out what I want to say. I’m open to any genre that allows me to access what interests me the most—the mysteries, silences, unanswered questions in our most intimate and important relationships, the way a dinner around a table can be quite suspenseful, the thrill of confronting the great danger of who we might really be, the romance that can follow. This can make my work difficult to traditionally market, but I am able to connect with readers in much more surprising ways. I am a deep believer in humanity still and I haven’t given up on the ability of strangers to pick up what I’m doing and see a bit of themselves in my books. Sometimes that’s the best twist of all.

Megan Abbott (Beware the Woman)

I really avoid thinking about genre in this way. For me, it would be a mistake to try to write to different audience or genre expectations, which would always be speculative anyway (or even anecdotal). I think you can only write the book you’d want to read and trust in that.

Danielle Trussoni (The Puzzle Master)

The question of following genre conventions is a complicated one for me, because I love blending elements from multiple genres into my thrillers. Essentially, I write what I like to read, and I’m the kind of reader who loves to be transported. If that means reading a novel with historical elements and shades of gothic horror and perhaps a little romance – and maybe even a touch of the supernatural – I’m all for it. While I know some readers prefer books that stay within traditional genre conventions, I write for readers who want to go to unexpected places.

Julia Phillips (Disappearing Earth)

The question of audience expectations can sit heavy on any author. Of course you want to write something that people will want to read. But it feels impossible to create exactly what that will be—after all, readers love both the comfort of the familiar and the thrill of the unexpected, and no one can say for certain what ratio of the two is ideal. In times of pressure, I like to look again at role model books, the novels that pull me in just the way I most want to be pulled. They’re part literary, part thriller, totally propulsive, and beautifully written, and the fact that they exist gives me confidence that there is space out there for all writers and all readers to do their varied things.

Clare Mackintosh (A Game of Lies)

Crime and thriller fiction can be exquisitely written (and a literary novel can be a page-turner) but beautiful prose should never come at the expense of pace. My early drafts are about nailing the elements that make a gripping crime novel – plot, twists, tension and suspense – and only then do I turn my attention to more literary nuances.

Sara DiVello (Broadway Butterfly: A Thriller)

We all want to keep readers engaged and turning the pages. As attention spans continue to shrink – I’m not sure how many of the classics would find publishers or hit bestseller lists today! – we’re challenged to find increasingly creative ways to captivate readers. Quicker pacing and twistier twists are two tools mystery and thriller writers utilize to great effect and strong results. In the end, I think reading is a lot like dating: you have to find someone whose voice doesn’t annoy you, who makes you feel safe, and who keeps you interested, engaged, and excited to see what will happen next. Not every book is for everybody…and that’s OK. My advice? Don’t change yourself to please a prospective partner and don’t change your book to please prospective readers. Your work will find the right readers.

Alyssa Cole (One of Us Knows)

I think thrillers pacing, like most things in literature, is subjective. I generally write “slow burn” stories, no matter the genre. There can be action, twists, and turns, but it’s a long burn until the story reaches the end of the dynamite’s wick and all of the elements combine and explode at the climax, hopefully in a way that satisfies most readers. Other stories work better with fast-paced, rapid fire storytelling. I don’t think there’s any particular pacing individual thrillers need to abide by beyond what the specific story being told calls for–and there’s a reader for every “speed” of thriller!

***

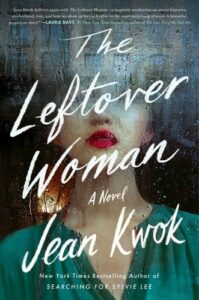

Most authors believe in simply writing what they themselves would love to read and the writers named above have composed some of my favorite books, novels that I thought about long after I read the final page. Indeed, the blurring of the line between literary and genre fiction marks an exciting era in contemporary storytelling. Even the act of reviewing has been democratized in the current landscape. In my new novel, The Leftover Woman, I wanted to write a a novel of suspense, filled with twists and turns, involving a murder, a young woman trying to recover her lost daughter, and love that blossoms in the most unexpected of places. At the same time, it’s an exploration of identity and belonging, motherhood and family.

I hope that the combination of literary and thriller elements in The Leftover Woman hit that perfect sweet spot for you, just as the books written by the authors in this article did for me.