Ocracoke Island, North Carolina, near sunset.

We’re standing on a narrow sand beach, the maritime forest of live oak, myrtle, and yaupon looming at our backs. To get here from the village, we walked a path through those ancient trees and passed a tiny cemetery with two headstones. Those graves are separated from the gnarled forest by the comfort of a lichen-covered picket fence.

Now on the beach, as we wait for the flaming colors of sunset, we’re looking at the part of Ocracoke Inlet called Teach’s Hole. There in that deep water Edward Teach, famed seaman and notorious pirate otherwise known as Blackbeard, met his end more than three hundred years ago. Royal Navy lieutenant Robert Maynard, the man who took Blackbeard, also took his head for proof. Some say Blackbeard’s headless body then swam three times around Maynard’s ship before sinking out of sight. Others say his headless body is buried in a mass grave somewhere on the island. Perhaps in the dunes because of easy digging. Or is it in the forest behind us? The path, now growing dark, will take us back past the two well-tended graves. Will it take us past the lost grave of Blackbeard, too? If not his, then some of his brethren?

Ocracoke is the southernmost in a string of fragile barrier islands called the Outer Banks off the coast of North Carolina. A scant two hundred feet at its narrowest and three miles wide at its most robust, Ocracoke is a spindly sixteen miles long. It’s awash in seashells and pirate history and afloat in ghost stories. Its iconic lighthouse, built in 1823, is the oldest continuously operating lighthouse in North Carolina and second oldest in the country.

Most of the island is federally protected as part of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore. In the two square miles at the southern tip, though, you’ll find Ocracoke Village, a thriving town since the early 18th century. It was also a haven for pirates during the Golden Age of Piracy which lasted from about 1650 to 1730. Besides Blackbeard, other famous pirates who called Ocracoke home are Stede Bonnet, known as the Gentleman Pirate, and Jack Rackham, known as Calico Jack. Calico Jack had two female crew members—Anne Bonny and Mary Reed. Bonny and Reed have gone down in history as Pirate Queens. There’s no proof they spent time on Ocracoke. There’s also no proof they didn’t.

Ocracoke was perfectly situated for pirates with their spyglasses trained on the maritime traffic along the east coast. Ships increasingly brought colonists, goods, and supplies to the growing settlements on the mainland. Enterprising pirates, who might be former British Navy sailors, merchants, or discontent members of the aristocracy, could hide on the backside of Ocracoke and dart out through Ocracoke Inlet for a surprise attack.

My husband and I first camped on Ocracoke in 1979. When our children came along we took them to the island every summer for years. It’s a place you can only get to by ferry, private boat or small plane. It’s a place where kids fall in love with the romantic popular culture image of swashbuckling pirates. Some of the parents do too. I sure did. I also fell in love with the island’s ghost stories. Who wouldn’t like shivering to the story of the fingerless skeleton? Or the less frightening story of gentle-natured Captain Joe Burrus, the island’s last lighthouse keeper, whose ghost has been quietly opening and shutting cupboards in his house since 1951? What’s he looking for?

Fittingly, I found my favorite Ocracoke pirate story by following the meandering dotted line of a treasure map. The line starts in my hometown, northwest of Chicago, where I read Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island in 7th grade. I loved the book and carved my own model of the Hispaniola. Following the dotted line, the next stop is Edinburgh, Scotland. I spent a year there, in the mid-70s, studying British Prehistory in a building in George Square. Who else spent time in George Square? Robert Louis Stevenson. The dotted line then travels a long way and eventually reaches California. Long after our trips to Ocracoke, my husband and I visited Monterey County and enjoyed hiking in and around Point Lobos State Natural Reserve. In the autumn of 1879, Stevenson stayed in a rooming house in Monterey for a few months. He took rambling hikes along the coast and inland as we did. There is credible speculation that he based his description of Treasure Island on Point Lobos. The point, with its rocks, pines, and crashing waves resembles Stevenson’s island much more than anything in the Caribbean.

With this accumulation of Stevenson connections, I followed the dotted line to the public library. Over several months I checked out Stevenson’s travel writings, poetry, his collected short stories, and biographies of him. I also requested a book called Treasure Island: The Untold Story by John Amrhein, Jr.

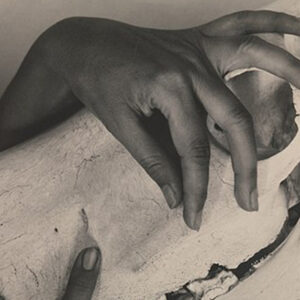

Amrhein’s research uncovered the story of two brothers, Owen and John Lloyd, Welshman who left their home in Wales and became successful, respected merchant captains in Hampton Roads, Virginia. In September 1750, they happened to be in Ocracoke when the captain of a hurricane-battered Spanish treasure ship, the Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, asked for their help. Worried that his ship would break up and the treasure lost, the captain hired the Lloyd brothers to remove the cargo to their sloops and ferry it to safety. The Lloyds transferred spices, silks, and fifty-two (some say fifty-eight) chests of silver pieces of eight to their ships. And then they fell prey to temptation. The Spaniards had no way to follow, so the Lloyds decided to sail for the West Indies with the treasure—more plunder than Blackbeard and all his brethren had ever laid their hands on. It was an audacious caper, a true “crime of the century,” and written up in newspapers all around the world. John’s sloop ran aground not far from Ocracoke, and he was captured. He, by the way, had a wooden leg. Owen, however, got clean away, making it to Norman Island in the West Indies, where he buried his part of the loot, with plans to return for it.

Stevenson’s Treasure Island is about an expedition to a Caribbean island to dig up treasure buried there in 1750, the year Owen Lloyd buried his plunder. Stevenson’s uncle sent him old clippings about Owen and John Lloyd’s piracy. Stevenson named his peg-legged pirate Long John Silver. Coincidences?

There’s much more to Amrhein’s meticulously detailed story, all of it worth reading. For me, though, Amrhein’s book is the X that makes the spot. I found my treasure and I’ve turned pirate myself. I’ve taken Owen and John Lloyd’s story and given them a younger brother—Emrys Lloyd. Sadly for Emrys, in my story he was the only fatality of that piratical adventure. Now he’s a pirate ghost haunting a shell shop on Ocracoke Island, forever wearing his knee breeches, buckled shoes, frock coat, waistcoat, and tricorn hat. He claims he was only a pirate by accident, only that one time, and it didn’t work out well. But can anyone trust a pirate’s word? Yo ho ho.

***