“If a man comes out of the field and goes on the picket line, even for one day, he’ll never be the same….The picket line is where a man makes his commitment, and it’s irrevocable; and the longer he’s on the picket line, the stronger the commitment….”

–Peter Matthiessen, Sal Si Puedes (Escape If You Can): Cesar Chavez and the New American Revolution

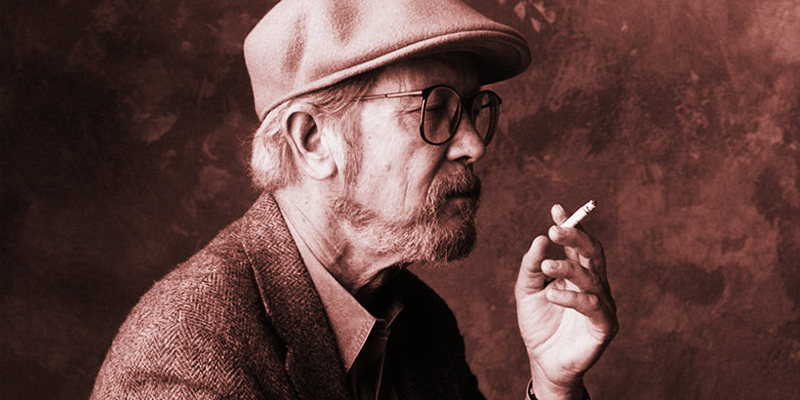

For six decades, Elmore Leonard watched as new readers discovered his Western and crime fiction through a revolving door of storytelling mediums: dime-store pulp magazines, paperback originals, hardcover editions destined for The New York Times’ bestsellers list, and, finally, Hollywood adaptations. Yet, when Leonard was commissioned to write his first “e-book” in mid-2000, the then-seventy-five year-old author—who famously penned all his first drafts by hand—didn’t even own a computer.

“I don’t feel that writing an e-book is at all different than writing a story for publication,” he admitted, “apart from the fact that I won’t be able to read it.”

While the debate regarding print-versus-digital has become largely mute, a quarter of a century ago, only one major American author had published an original piece of fiction solely for online consumption—Stephen King, with his serialized The Plant, in July of 2000. Predictably, publishers took notice, including Steven Brill, the founder of digital media start-up, Contentville.

Brill envisioned a subscription-based online magazine, which would include a high-profile piece of original fiction within each monthly issue. Despite Leonard’s indifference to the digital medium, he accepted an offer to be the magazine’s first featured author.

Leonard’s contract called for three individual works to be digitally released on Contentville throughout the year. In exchange for an original story with which to make his debut, Leonard was granted the right to provide two previously-written pieces of “novella” length for the ensuing contributions.

Yet, when Leonard was commissioned to write his first “e-book” in mid-2000, the then-seventy-five year-old author—who famously penned all his first drafts by hand—didn’t even own a computer.He was implored to use recognizable characters from earlier books—such as those from Get Shorty and Rum Punch—all of which proved contractually unavailable due to their use in recent film adaptations. Instead, Leonard used the opportunity to resurrect another one of his personal favorites who hadn’t made a literary appearance in half a decade: Deputy U.S. Marshal Raylan Givens. The resulting novella, Fire in the Hole, so successfully brought the character of Givens back to prominence that it caught the attention of television producer Graham Yost, who adapted it as the pilot for the eventual smash hit television series, Justified.

However, this left Leonard with two stories left to submit for the year. Combing through his personal archive, he selected two unpublished longform pieces that hadn’t yet seen the light of day: the completed teleplay for a proposed two-hour Florida-based crime series pilot entitled Stinger (co-written with director William Friedkin) and a 1970 novella called Picket Line. Ultimately, Leonard chose the latter as his next submission.

Just prior to Picket Line’s publication, however, the unexpected happened: after only ten months of operation, Contentville went under, and Leonard refocused his full attention to writing Tishomingo Blues. And so, the long-shelved novella was reshelved within the author’s home archive.

Until now.

Both an anomalous treasure for devoted Leonard fans and a perfect introduction for new readers, Picket Line finds its author at an important crossroads in his career. When Leonard’s agent, the high-powered Hollywood deal-broker, H.N. Swanson, first presented the proposed film project that would become Picket Line in February of 1970, the author had only recently made his hard-earned “contemporary crime” debut away from the Western pulp genre.

The Big Bounce, however, had garnered little to no attention either in book form or in its disastrous cinematic adaptation. And while Leonard’s follow-up novel, the prohibition era “semi”-Western, The Moonshine War, had earned strong reviews, its film adaptation, too, sunk hard at the box office.

H.N. Swanson continued to shop the author’s dual talents as novelist and screenwriter-for-hire—a strategy that would also qualify Leonard for WGA acceptance. Yet, following a five-year hiatus from publishing fiction, Leonard was more enthusiastic to reenter the literary arena, and soon viewed screenwriting assignments as mere means of employment.

Of the half-dozen offers Swanson threw Leonard’s way, he was most adamant that his reluctant client accept “the fruit picker”; its themes, he insisted, were of a socially-conscious area Leonard wanted to explore, and its setting was reminiscent of The Big Bounce. Plus, thanks to the unique two-man production team that had approached Swanson, the project had already been greenlit by Columbia Pictures.

Together, partners Howard Jaffe and Edward Lewis seemed to represent both the old studio “system” and the Progressive nature of the “New Hollywood.” Fifty-year-old Lewis had a working relationship with legend Kirk Douglas as far back as 1956, ultimately co-producing the star’s Lonely Are the Brave and Spartacus, while the younger Jaffe, then in pre-production for Harold and Maude, had just produced Goodbye, Columbus—both countercultural statements aimed at a younger generation of moviegoers.

Although an unlikely duo to join forces as a moviemaking team, Lewis trusted Jaffe’s instincts in attracting audiences through projects mirroring the social turbulence of the times. For their first collaboration, Jaffe pushed for a labor of love he’d been harboring for years: a fictionalized account of the 1965 Delano “grape strike” and its leader, Mexican-American union and civil rights advocate Cesar Chavez.

Beginning in March, 1970, Leonard and Jaffe stayed in constant contact regarding the “fruit picker” project, then under its working-title See How They Run. The young producer sent copious amounts of research materials and character and story ideas to Leonard’s office in Birmingham, Michigan, mostly sketches of archetypes he’d liked in films The Defiant Ones, Cool Hand Luke, and Viva Zapata!

Leonard supplemented Jaffe’s ideas with his own evolving interest in migrant fruit pickers and their union woes. While researching The Big Bounce four years earlier, Leonard had saved numerous articles from The Detroit News about Michigan-bound Mexican braceros—migrant workers who slaved over fields of beets, cherries, strawberries, and pickles—all of which were near Leonard’s home. By the end of April, Leonard had poured through Jaffe’s mandated readings of Peter Matthiessen’s biography, Sal Si Puedes (Escape If You Can): Cesar Chavez and the New American Revolution and Eugene Nelson’s Huelga: The First Hundred Days of the Great Delano Grape Strike.

With a clearer view of the civil rights themes he felt Jaffe wanted to hit, Leonard swapped out See How They Run (and Jaffe’s other tentative title, Huelga!—Cesar Chavez’s battle cry—for a title he felt better symbolized the moral “line in the sand” over which each character would cross. He wrote Jaffe, “Now consider for a moment that individual commitment is the key idea: a man standing up to be counted in spite of his fear of the overwhelming odds against him.” For this, Leonard saw only one title—Picket Line.

But with the change of title, other divisions began between the producer and screenwriter. In Jaffe’s earliest notes, he had implored Leonard to draw inspiration from “the Joseph Wiseman character in Zapata,” a sort of “Christ figure who couldn’t make it in his own country [and thus] went to the U.S. to reform and help and preach there….”

But as soon as Leonard factored those elements into the script’s chief protagonist, more notes soon followed with additional dictums. In the second batch, the producer envisioned the protagonist as a riff on real-life Chicano Movement activist Reies Tijerina who, in 1967, had stormed a New Mexico courthouse in an attempt to make a citizen’s arrest of the local district attorney “on behalf of the Mexican and Hispanic community,” taking along two hostages before his eventual capture.

Jaffe had referred to his fictionalized version as “Teorina,” and Leonard rewrote his outline and draft to reflect the new changes. However, he’d made one major alteration of his own; rather than using Tijerina as the protagonist, Leonard molded him into a completely new character—a militant, yet philosophical, doppelganger to the “Cesar Chavez” protagonist.

In mid-April, Leonard was again assigned a new angle of research: “Although we would have to handle any matters of the church very delicately, we may be able to give our picture a Man For All Seasons dimension that we never before considered,” Jaffe wrote. “I’ve underlined passages that I feel might stimulate you, but I’ve probably missed much that might trigger new attitudes in your mind.”

For this, Leonard clipped and studied recent events within the Catholic Church and its social stance towards the various “pickers” strikes. Although much of the inspiration Leonard drew during this period would be better utilized in his then concurrently in-progress screenplay, Jesus Saves (later drastically reworked into his 1977 novel, Touch), Jaffe’s latest direction did help finalize Picket Line’s final two primary lead characters.

Soon, the militant Reies Tijerina-inspired urban warrior became “Francisco ‘Chino’ de la Cruz”—the yin to the Cesar Chavez-inspired union leader’s yang. Imagining a forceful “George C. Scott-type” in the role, Leonard had given the “Christ-like figure” the name “Vincent Mora” (memorably repurposed in the author’s gritty 1985 bestseller Glitz).

However, Jaffe would claim that the dramatic ensemble Leonard had worked up was a far cry from the suspenseful Medium Cool-style mock-documentary he’d envisioned for Columbia Pictures (a factor the producer had failed to mention earlier, nor his affinity for the “Billy Jack” character played by Tom Laughlin in 1967’s The Born Losers). As a last-ditch effort to get his narrative ideas across to Jaffe, Leonard quickly used the same strategy as Graham Greene while in pre-production for Carol Reed’s The Third Man, writing a prose version “typescript” of the plot, thus spelling out the imagery and nuanced characterization needed for the upcoming film.

Unlike Greene’s efforts, however, what quickly evolved into a polished novella was written in vain: on August 11, H.N. Swanson reported back that Jaffe had nixed the entire project. “I spent quite a bit of time this afternoon with Howard Jaffe,” Swanson wrote. “He feels that he wouldn’t be able to turn [Picket Line] into the kind of story he wants and therefore suggests we offer it elsewhere.”

Leonard would do just that, rewriting the story for Clint Eastwood into one of a war veteran-turned-melon farmer run afoul of a local mob enforcer. While retaining both the most noble qualities of Vincent Mora and the militant pragmatism of Chino Rojas, the renamed “Joe Doran” was reconstructed as a protector of the many migrant employees who work his fields while waging the one-one war against a newly-created antagonist hitman that comprises the story’s rewritten final two-thirds.

In the new treatment, Leonard established early that Doran always paid his employees fairly, thus removing all mentions of picketers and union woes. For Eastwood’s personal convenience, Leonard had even transposed the action from San Padro Island in Bravo County, Texas to Carmel, California—although an apparent disagreement regarding which harvest the farmer should grow proved the deciding factor for actor-director instead making High Plains Drifter; Eastwood had insisted on local Carmel artichokes over Leonard’s preferred honeydew or watermelons).

And although Eastwood passed on the treatment—retitled Joe Doran Is a Dead Man—fellow action star Charles Bronson did not; by 1974, Picket Line was fully reconceived and reborn as Mr. Majestyk.

When first accepting Howard Jaffe’s screenplay assignment, Leonard hadn’t the intention of concurrently writing Picket Line as a novella; only out of necessity did he fall back on his greatest strength—prose laden with realistic dialogue—to write it in fiction form during the summer of 1970. But the finished manuscript would hold more significance Leonard’s evolving contemporary style than either he, or his future critics, then realized.

During the course of the previous year, he had written the novel and the screenplay for The Moonshine War concurrently—a laborious process that had included numerous research expeditions to rural Kentucky. When only the novel proved successful did Leonard accept more “work-for-hire” screenwriting work, intending to focus more energy towards his fiction.

During that period, he had been testing out changes to his prose style. Taking a cue from his ultimate hero, Ernest Hemingway, Leonard aimed to strip as much exposition as possible, allowing for his characters to dialogue to realistic present themselves through dialogue and behavior. (He would later admit that his “eureka moment” came with his famed reading of George V. Higgins’s The Friends of Eddie Coyle three years later.)

Because Leonard didn’t intend for Picket Line’s immediate publication in 1970, he freely experiments with narrative devices that would soon define his trademark signature sound; readers will notice his heavy use of the “Free Indirect Discourse”—the objective narrative voice weaving with the sound and attitude of each character’s own interior monologues—as well as the switching of multiple perspectives. Leonard first learned the value of these devices with Picket Line—his intention for a lush character-driven film treatment leading to the discovery of the powerful narrative voice that he would refine over the next four decades.

As Picket Line opens, Bud Davis—a white, young suburbanite holding a summer job picking honeydew melons for Stanzik Farms among the many migrant workers—watches from afar as the head of the Valley Agricultural Workers Association [VAWA] gets into a heated altercation with the Wade County Rangers (a stand-in for the real-life Texas Rangers). Inspired by the union leader’s bravery, Davis joins up with the strikers, making him a marked man to both his employers and the white citizens who now view the young man as a traitor to his race.

Leonard had inserted the “Bud Davis” character at the behest of Howard Jaffe. After imploring Leonard to view A Man For All Seasons, the two agreed that an “everyman character,” placed at the forefront of the story, could act as surrogate for the viewer.

For this late addition, Leonard had concocted the peripheral protagonist Davis, describing the character to Jaffe:

He’s a free…white twenty-one year old American boy who’d come down here for a summer job because he knew the son of a grower and, Jesus, he never expected to get mixed up in anything like this. You know him…not simply from the angle of audience identification—but because I feel Bud Davis can take the story out of the realm of pure melodrama and make it a human experience that has vivid parallels in other facets of life.

What Leonard had done with Jaffe’s original protagonists, however, had drawn the producer’s ire: in Leonard’s Picket Line, “Chino Rojas,” the Tijerina figure was no longer “a rural nationalist in a big Chihuahua hat,” but rather an ex-con out of East Los Angeles—”a street fighter turned revolutionary” who saw the picket line as an opportunity to “get back at Whitey through a legitimate venture.”

Likewise, the Chavez character, now “Vincent Mora,” represented more of Leonard’s own views on the modern Catholic Church and his own Jesuit-inspired faith than that of Jaffe’s cinematic social hero. Although enigmatic and stoic throughout the novella, Leonard’s plans to reveal Mora as a defrocked priest and his cowardice which leads to Chino’s ascent as revolutionary leader—obviously rattled Howard Jaffe as much as young Bud Davis, whose own story finds him escaping back to suburbia like a thief in the night.

In Picket Line, readers will see an early leanness to Leonard’s prose, and a coolness in how characters’ looks and behaviors are only given through the eye of a different beholder. They’ll also see Leonard toy with symbolism (a bug sucked and splattered against a windshield, hinting at the driver’s own fate to come); philosophical ideologies confronting each other (a militant urban freedom fighter debating a man of the cloth regarding moral responsibilities); and action scenes fueled not by crime, but by social reparation (Chino’s massacre of freshly-picked honeydew melons—later a memorable centerpiece in the film of Mr. Majestyk).

Longtime Leonard fans will also spot character archetypes and hints of plot-points from the author’s future bestsellers, as Vincent Mora’s clergy-in-disguise routine would later be used in Leonard’s Touch, Bandits, and Pagan Babies. Likewise, Chino Rojas’s predilection for acts of urban terrorism predate those of Freaky Deaky’s Robin Abbot, and the final (though unpublished) confrontation scene between Mora and Chino mirrors the showdown from Leonard’s 1982 novel, Cat Chaser.

But Picket Line also finds Leonard at his most overtly literary, substituting the threat of crime or menace for the suspense of human drama; faith, racism, and views of the social “outsider” governed by not one, but two, patriarchal forces—in this case both the corrupt Wade County Rangers and the operators of Stanzik Farms—would all be right at home within the works of John Steinbeck.

Picket Line is also structurally unique as Leonard’s only story to span the exact length of a single day, infusing both a voyeuristic perspective and a sense of urgency—more elements honed within his later work.

Today, critics regularly cite the April, 1974 release of Fifty-Two Pickup as the proper starting point for the “contemporary” Elmore Leonard sound; however, he’d actually completed a novel in that style earlier that same year. Although published by Dell with release of United Artists’ Mr. Majestyk two months later, Leonard’s corresponding novelization had been written first.

In fact, as the first piece of fiction he’d touch since shelving Picket Line, Leonard had used Mr. Majestyk to woodshed his narrative “disappearing act,” admitting as much in a letter inquiring of H.N. Swanson if the agent believed readers could easily follow the new book’s multiple character viewpoints. Having been the one who’d personally recommended Leonard read The Friends of Eddie Coyle, Swanson was enthralled with the results.

As his earliest attempt at a modern “sound,” fans and aspiring writers who continue to look to Leonard for guidance will find the publication of Picket Line a long time coming.Unfortunately, movie novelizations rarely receive critical reviews and usually vanish from stores the moment its promoted film leaves cinemas. Ultimately, Mr. Majestyk lapsed out of print for a decade, only becoming again available in the mid-1980s during Leonard’s rise to superstardom; and with the shuttering of Contentville in 2002, so ended any plans to release Picket Line during Leonard’s lifetime.

As his earliest attempt at a modern “sound,” fans and aspiring writers who continue to look to Leonard for guidance will find the publication of Picket Line a long time coming. The experience of writing Picket Line not only provided its author with another hard-earned learning lesson from the salt mines of Hollywood, but, more importantly, confidence in the new narrative style he was developing.

A rare hybrid of his Western sensibilities in a contemporary setting, Picket Line presents Leonard as an even rarer form of writer: one who could tackle the harder subjects of daily American life from the dual angles of entertainment and objective observation.

It would be another fifteen years after completing Picket Line that Newsweek crowned Leonard “the Dickens from Detroit.” But it was with Picket Line that Leonard drew his own line in the sand.

*

From the introduction to Picket Line: The Lost Novella by Elmore Leonard. Copyright © 2025 by C. M. Kushins. Excerpted with permission of Mariner Books, a division of HarperCollins Publishers.

***