You can tell me anything.

When you’re in this room, and we’re sitting across from each other, and your mind is reeling with all the bad things you’ve done to people, and all the bad things they’ve done to you, you can let it all out into the air between us. All the weird sex stuff, the compulsive jerking off, the period blood staining the gym shorts when you were thirteen, the infidelities, the regret about having kids or not having kids. You can tell me about the time you did mushrooms and made out with a window for three hours, or that time with your dad’s friend, that time you felt a stranger’s boner press against you on the subway, how you wish your mother would just die already, how you accidentally screwed that IT girl in the conference room, how the rape scene in Deliverance turns you on, how you obsessively think about sex or food or death, how you should get more sleep and make more money, how you should eat more ugly foods and buy more reusable bags, how you lied about voting for Obama. How you wish you were a better person, a better spouse, a better parent, a better worker, a better citizen. How there is something else you should be doing, how you feel trapped in this life and in this body and every day it’s like you’re living and reliving that Talking Heads song. Well, how did I get here?

You can tell me any of it; you can make a list ahead of time or just barf it all up when you sit down, and I will never tell anyone.

Imagine weighing yourself on a bathroom scale, and all the little black lines represent all the things you can tell me-the dial can bounce up and down as many times as you want, and your secrets will be safe with me. There’s only one red line we have to worry about, only one little tick mark where the dial has to land in order for me to break my promise, and that would be if you told me you were going to kill someone.

My anorexics love this metaphor.

And yes, of course, if you were going to harm or kill yourself, I’d have to make a call, but if you’re telling your shrink in person you’re planning to do yourself in and didn’t happen to stash your chosen weapon in your purse, chances are you are open to being talked out of it.

My patients call me Dr. Caroline for a couple of reasons. One, because the goal is to make them comfortable, to convince them I am like their smart, impartial friend who has their best interests at heart. Two, because of the Marvel thing. There is a superhero, Doctor Strange, who travels through time/space and knows physics, I guess? I’ve only seen a couple of those movies with my family and don’t care for them. All that Sturm und Orang, so much emotion and wrestling with life choices. I get that day in, day out, eight-thirty in the morning to eight-thirty at night, so when I go to a movie, I just want to see cars blow up and perhaps a nice pair of tits I can admire wholesomely from afar.

I live in a wealthy neighborhood in a wealthy city. Where Botox meets craft butchery, and even the homeless people can do a mean upward-facing dog. It’s Brooklyn, so there is still a little edge here and there-the tall, thin vape twins who can barely keep their eyes open even as they blow smoke into your face as you pass them on the sidewalk; the guy with the elaborate facial tattoo asking for coffee money in front of the pediatrician’s office; the lady who sits on a tuffet of garbage bags in the bank vestibule. I like this about where I live. I grew up in a sleepy Wisconsin suburb where the most exciting thing that ever happened was two rival dentists got into a fistfight at a sports bar once. When I came to New York City for school, I never looked back. My patients are primarily from the privileged masses: Prospect Park soccer moms and aging hipster dads, anxious gainfully employed millennials and their oddly relaxed unemployed counterparts.

The lot of them were silenced for a few weeks by the collective sonic boom of the pandemic. In the beginning they resisted the Zoom sessions, but then they caved one by one, and those first appointments were cacophonies of panic; whatever trivial transgressions they’d experienced or caused in their former lives were crushed like a kombucha can under a Prius tire. Very few of them got the virus or knew anyone who’d died, but still, their wild fear seeped through the screen, and I was there to absorb it.

I felt extra-useful in those days, shepherding them from one day to the next, so many of them moving through the most precious realizations (I should spend less time on social media and more time with my kids!, I should listen more than I talk!, I should stop forcing people to look at my dick!). But then, after a couple of months, they realized they would probably not die, that they were safe in their little corner of the world, so they went back to old habits and old complaints, running out our time together wringing their hands about emotional affairs with their work husbands, or how Dad had yelled too much, and I’d send them off with a virtual pat on the head and a prescription for their Lexapro/Klonopin refills.

So it’s not triage in the ER, who cares? This is my job, and, not to put too fine-tip a point on the scrip pad, all those complaints and meds paid for the brownstone where I live with my family on the parlor and upper levels and meet with patients in the ground-floor office.

I still get a flutter of excitement when I see a new patient, because it really is like a blind date in many ways: will we gel; will we click; will he recognize me as a fellow human and show me something. But between you and me, it doesn’t matter if he decides to show me anything, because I’ll see it anyway. I watch the hands; I watch the legs crossing; I watch the gazes toward the window. I listen for the vocal modulation when he’s speaking about money/sex/Mom/Dad. Give me an hour, I’ll tell you who you are.

Second thought, make that fifty minutes.

It’s a steaming June day after arguably the worst year humans have seen in a good long while, and a new patient is coming without a referral, which is even more exciting, a blind-leading-the-blind date.

There is an internal staircase leading from my home down to my office, but I walk outside and down the stoop and enter through the door under the stairs just so I can see what he will see: in front of the windows, a cream-colored couch with a small cylindrical table at one end where he can place his phone and water bottle. Also on the table are a box of tissues and a dimmable-display alarm clock, which is for me to keep track of the time. He will also have an identical clock to look at, on another cylindrical table next to my wood-framed chair, an office chair that isn’t supposed to look like it belongs in an office. But he has a choice-on the other side of his table is a plush swivel chair.

Where he sits will tell me the first thing. Most people will take the couch because it is more directly positioned in front of me. They’re not thinking too much about it. But those who choose the swivel chair don’t mind sitting at an angle, or they enjoy swiveling, or they don’t want to feel like a patient; they’ve been taught to associate couches with shrinks and they don’t want any part of that. So if they choose the swivel chair, they’re making a little statement, crossing their arms and digging in their heels: Nope, not gonna tell you anything.

There are two doors behind my chair, one leading to the kitchen,

where I keep a Nespresso machine for myself, and the other to a half bath that patients can use. There’s a full-length mirror hung on the door of the patient bathroom, and how long they spend in there after the business is done, scrutinizing, muttering, fixing hair, and checking teeth, also tells me a great deal.

I don’t use the patient bathroom—for that I’ll go upstairs to my home-but I do like to review myself in the mirror. I wear a white suit for my sessions every day. Alexander McQueen wool blends—single-button blazer with boot-cut pants. The white is for both of us: for them, to see me as a blank sheet of paper on which they can write whatever they want; for me, an extra boundary. I’ve known therapists who wear distressed-hem jeans and cowl-neck sweaters with their patients, who sit cross-legged on beanbag chairs, and that is just not for me. It’s not a fucking square dance; it’s work.

The patients need the boundaries, even if they buck against them. And some, I would say most, end up appreciating them. Where will Nelson Schack fall?

I position the two linen-covered pillows, one to either side of the couch. Only certain patients use the pillows, always for support—clutching for emotional, tucked behind them for lumbar.

I adjust the temperature on the split AC unit by one degree. Some patients expel their sadness through sweat instead of tears, I’ve found, so better cool than hot.

I check myself in the mirror once more. The suit is pressed, but the silhouette is simple-I don’t look like I’m going to a Wall Street hedge fund or a wedding. Every morning I blow out my hair and style with a rotary brush; the result is natural but controlled, which is the goal.

Then come the three tones of the digital doorbell.

I open the French double doors into the hallway, where there is a single chair and a small table with recent New Yorker magazines in a fan. I answer the front door, and here is Nelson Schack. An inch or two taller than me, slender. Hair almost buzz-cut-short but not quite. Swimming-pool-blue eyes and clean-shaven except for a spot missed under the nose. Collared polo shirt, sweat circles in the pits. Khaki pants with slanted lines crisscrossing at the knee, ironed haphazardly.

“Hi, Nelson,” I say. “I’m Dr. Caroline.”

I hold up my hand in a still wave. Even though he and I have sent each other copies of our vaccination cards via email, I don’t need to put anyone through the pros and cons of a handshake with a stranger.

“Hi,” he says, only meeting my eyes for a moment. “Come in,” I say, warm but professional.

I hold the door open for him, and he walks past me, giving off a scent of a musky deodorant with a little BO spike.

He stands in the hallway as I close the door, and then turns to me for instruction.

“Please, have a seat,” I say, gesturing toward the office.

I know he’ll take the couch before he takes the couch. He’s nervous; he’s never done this before; he won’t even think about it.

He sits on the couch, the middle cushion, and crosses his arms over his chest, his fingers cozy in the twin saunas of his pits.

I slide the double doors shut and take my chair.

“Before we begin, I need to make you aware of one thing,” I say.

He gets a caught-raccoon sort of look, so I don’t keep him in suspense.

“You can tell me anything,” I say, turning my finger in a small circle. “This is a safe space.”

Then I smile, and he smiles, relieved. “What brings you here today, Nelson?”

He laughs and puts his hands on his knees, then says, “It’s a couple of reasons, Doc. I’m just not sure which one to talk about first.”

I nod, because I know. Their first time in therapy, they don’t know where to start. How did my life end up this way? is a big old rabbit hole to fall into, every rock you hit another loved one to blame.

“Why don’t you try just saying whatever comes to the surface first?” I ask, as if I’ve never suggested it to a patient before.

“Yeah, that’s a good idea,” he says.

His voice is unexpectedly high, as if he’s leading up to a question. Then he pats his knees with an air of decision and says, “Well, here goes.”

I give him another smile meant to convey the tell-me-anything rule, and he must truly understand it, because then he says something that I never could have predicted he or any other patient would ever say to me, not in my thirteen years of primary and high school, twelve years total in undergrad, med school, residency, and eleven years of private practice:

“I think I’m going to kill someone, Doc,” he says in that strange high register, his eyes scanning the corners of the room. Then he looks straight at me and says, “And I know who you really are.”

I’ll tell you a little bit about narrative omission in therapy. All of us—you, me, your mom, the dry cleaner-we all rewrite the stories of our lives as we tell them to other people. Sometimes we change things, but more often than not we just omit. We tell our listeners what they need to know, and nothing else. We do that because it’s human nature to get to the point, and to a lesser extent not bore the listeners. Why? Because we want them to keep listening to us.

No one cares that a Paleolithic-era caveman took a dump in a hole or was on the receiving end of a nut-cracking BJ from the missus. We care that he killed the bison, and somehow, even with his underdeveloped Neanderthal brain, he recognized that, so that’s what he painted on the wall.

My patients do this all the time; however, there’s a slightly more devious edge to it. I have a patient, let’s call her Meandering Marjory. Marjory drinks too much and pretends she doesn’t, which makes her as unique as half of America. So sometimes she’ll come in and tell me all about her day leading up to our appointment, how she got coffee in the morning and dropped the kids off at school and went grocery shopping and walked the dog, and it takes her twenty minutes to get through this much of the story and she keeps blowing air out, her upper lip flapping like a doggy door, and adopts a street accent arbitrarily (“You feel me, girl?”), and yet it takes me about thirty seconds to get her to admit that she also drank a pint of dark-and-stormies before showing up.

If you have been in therapy, you have done the same in some way. Sometimes you do it to cut to the chase; sometimes you do it because you don’t want your therapist to know something.

Here’s a hot tip: we know.

But rest assured, we do it, too. Because we’re all cavepeople together! All of us shitting in holes and performing/receiving fellatio, and yet we only pick up the charcoal to draw that pesky bison.

So when I said I grew up in a sleepy Wisconsin suburb where the most exciting thing that ever happened was a fight between two dentists at a sports bar, that wasn’t the whole story. Dr. Brower and Dr. Nowak did get in a fistfight at Gator Sam’s, but the town is known for something else entirely.

It made national news at the time, but Jeffrey Dahmer had been caught only two years before, and people on the coasts can only take so much news about the goings-on in the middle, even if it’s bloody. But in the Upper Midwest it was a big deal for a while.

In late June of 1993 in the village of Glen Grove, Wisconsin, a man murdered his family with a pair of hedge shears. The wife was thirty-eight at the time of her death; the children sixteen and thirteen. The blades on the shears were eleven inches long.

About now you’re rushing, skimming, skipping-you want to know it all, don’t you? You’re desperate for details-how did he do it with the shears, did he stab them, cut off their fingers or their heads? Or worse, you think, did he cut out their hearts . . . did he cut out their hearts and eat them whole, did the police find a pentagram drawn in blood on an altar in the basement?? No, wait, did he . . . no, it’s just too awful, he couldn’t have . . . did he have sex with their headless fingerless hollow corpses???

We all think we’ll be the ones so mature and self-realized that we won’t look at the car accident, but of course we look; we hope to see something horrible in order to capture the relief that it didn’t happen to us. It’s natural! Don’t beat yourself up about it, but really, satanic-inspired cannibalism and necrophilia are not that prevalent, despite what some swaths of the intellectually damaged population would tell you.

Yes, the Glen Grove murders were gruesome and gory and worse than the worst images from the first slasher movie you saw, which have burrowed into your unconscious so deeply you sometimes wonder if you didn’t actually imagine them yourself-Jason chopping off his mom’s head, Freddy gutting Johnny Depp (before he was Johnny Depp).

And I happen to have a personal connection to the event, which is not exactly a secret but also not exactly broadcasted, and so when Nelson Schack offers this pair of confessions, I think it best to focus on the one that feels more urgent.

“How long have you been thinking about killing someone?” I say. He laughs, but not nervously. He seems delighted by my question. “This one?” he says. “Not long.”

He touches his face, fingers to lips and around to the back of the neck. They are the moves of an anxious person, but again, he does not project anxiety. His eyes flicker like candlelight, and his smile, though slight, is genuine. Someone with a wonderful secret. He dropped “this one” thinking I may not notice. This one, as in there have been others. Though I’m always driving, I sometimes like to let my patients think that they are. It occurs to me that Nelson could use a sudden turn.

“Have you decided whom you’re going to kill yet, this time?” I ask, casual as can be, as if I were asking one of my older son’s idiot friends which extracurricular sports he’s doing in the fall.

He stops moving his hands around, and they stay at the back of his neck. Something doesn’t please him. Loses the smile.

“Yes, I have.”

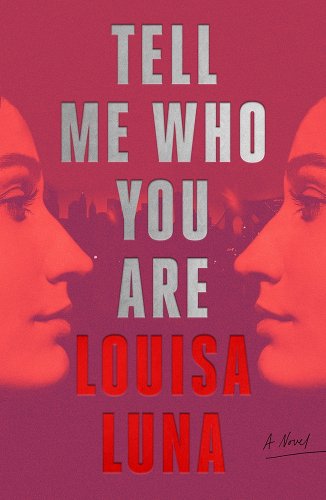

Excerpt continues after cover reveal.

I realize now would be the time for me to get nervous, if I got nervous. Which I don’t. Nelson Schack may be a few inches taller than me but doesn’t look like he works out like I do. I can’t make out his biceps, but from what I see of his forearms, I doubt he’d make it through a single resistance class at Pure Barre. The way his clothes hang suggest he’s not carrying a weapon, and if he is, it’s slight and ineffectual. Likely similar to his genitals and/or prefrontal cortex activity.

“Is that information you’d like to share with me?” I ask. “Uh, no, not yet.”

“Okay,” I say. “We can pause on that. Have you decided the method of how you’re going to kill this person?”

“Oh yeah,” he says, as if a familiar song has just spun from the playlist. “Pretty sure I’m gonna just let her starve.”

“Hm,” I say, because if it wasn’t Twenty Questions before, now it is. “So does this person live with you?”

He grins. “No.”

“Is this person a relative?”

“Uh-uh, no. She lives in the neighborhood, and I’ve been watching her awhile. You know her, too, Doc.”

He certainly likes a challenge! In residency I treated a handful of real grade-A antisocial personality disorders-people you would call sociopaths and psychopaths. What they all shared was an absence of remorse, a tendency to lie, and, more specifically for the psychos as opposed to the socios, a pattern of manipulation and aggression. But then there are those I call the fanboys. These are the ones who’ve gobbled up books about the Zodiac Killer and Ted Bundy, who obsessively watched and rewatched The Silence of the Lambs and possibly Manhunter; maybe even kicked back with a High Life on Wednesday nights to watch Criminal Minds, but that really is scraping the bottom of the serial-killer-narrative barrel.

Nelson Schack reads more fanboy than psycho to me. His intention is to provoke, daring me to join the game. He might have done some cursory research about me, but he doesn’t know enough about me to know that I have won nearly every game night my family has had since my sons were old enough to fit the little plastic wedges inside the Trivial Pursuit piecrusts.

I say nearly, because I’ve had to throw quite a few games. Child psychologists will say it’s important to let your children lose because it prepares them for coping with failure in the world, and ultimately I agree, but sometimes they just need a win. Boys especially. And yes, I let my husband win some, too.

Because I also like to get laid.

So okay, Nelson, I’ve got the empty pie, my seven letter tiles (all consonants, by the way), a full set of chess pieces, and a fire-engine-red gingerbread boy from goddamn Candy Land. Winner goes first.

I smile and say, “I know a lot of people. You mind narrowing it down for me?”

He brushes his chin with his fingers and says, “You know who she is but you might not know her personally.”

“Is she a local celebrity?”

Quickly I flip through the mental Rolodex of famous and semi-famous in our neighborhood, which may be larger than you’d think. Mayoral candidates, actors, musicians, restaurateurs, writers. Once I saw Padma from Top Chef at the roller rink in Prospect Park. She was nine feet tall on skates.

“No. Some people know her name.”

“You could say that about anyone, I think,” I offer.

His face sinks and sags. Suddenly he looks jowlier than he did when he first sat down.

“You don’t believe me,” he says. “What makes you say that?”

“You know, the way you’re joking around.”

“Nelson,” I say. “All I know is what you’re telling me, and I take everything you’re saying very seriously. However, I notice that you’re only telling me a little bit at a time, which implies you’d like me to take some guesses and make some observations.”

He nibbles his lips into a pout, and whatever might have been edgy about him dissolves. He’s like every other one of my patients, especially the men, awaiting the kitten licks to whatever fragile wound is throbbing just beneath the surface. It will take me, as always, being the bigger person.

I’m sorry I’ve misunderstood you,” I say. “If you like, we can start over. You can even leave the room and come back in,” I say, waving in the direction of the door. “We can pretend we’ve never met.”

He smiles now, charmed by the idea and my apology.

“Do people do that?” he says, letting his head down so that it’s almost resting on his shoulder. “Start over?”

“Of course. Getting off on the wrong foot is part of being human. I can’t tell you the number of times a new patient has decided to come through the door for the first time twice.”

I will tell you the number of times: zero.

He lifts his head and appears to be thinking about it. Even though I just came up with the idea, it’s fairly irresistible: To reset. Wouldn’t we all like it, even if it’s just from this morning, would we waste less time reading garbage on the internet, would we eat the muffin, would we call our mothers? The answer for me for all three would be no, but I’ll agree that at least to have the option is intriguing.

“Okay,” he says. “Okay?”

“Yeah,” he says, brushing his fingers over his chin again. “I’d like to do that. Go out and come back in.”

“That’s great,” I say, standing, as if this is all pro forma.

He stands, and he stares blankly past me, no longer engaged. “Please,” I say, gesturing toward the door.

“I just go out and come back in again.”

“That’s right, Nelson. Just start over.”

Something about that lands right where it should, because he brings his focus back to me, blue eyes lighting up. Could he be attractive? Not in his current state, to be sure, but maybe some baggier clothes, a tattoo here or there, hair a little longer-he could be a moderately cute bartender.

He heads for the double doors and pulls them open, and I follow, still surprised we’re doing this little bit of sitcom staging. Then he passes through the hallway and goes through the front door.

“Thanks, Doc,” he says, fully outside now. “For all the great advice.”

“You’re most welcome.”

I shut the door and wait a minute, don’t watch him through the peephole so he can’t see the glass grow dark.

He doesn’t buzz or knock. I finally look through the peephole, and he’s gone.

I open the door and walk through the small paved yard, through the front gate, and look left, then right, and I see him, arms heavy at his sides, trudging toward the corner. I stand still, waiting, but he doesn’t make a move to return or even turn his head back to look at me.

I cough up a closemouthed laugh. The turn of events is refreshing. Well done, Nelson. Good job sticking the landing on Gumdrop Pass.

I have at least a half hour before my next appointment, Churlish Charlotte, since Nelson didn’t take his whole slot. I give all my patients little nicknames, as alliterative and Garbage-Pail-Kids-like as possible as a means to remember them, of course, and maybe also keep myself amused. Churlish Charlotte runs a yoga-studio-slash-custom-tea-shop, and has been a patient for four or five years. For someone who should be blissed out on endorphins from pigeon pose and turmeric-cinnamon blends, she’s generally pretty whiny and pissy. Even during the darkest pandemic days she found something petty to obsess over in every session, like how Whole Foods kept running out of the chickpea pasta she has to have because whole grains give her gut-bloat.

I walk up the steps of the stoop and press the passcode into the keypad, go inside. The parlor level of my house smells like rosemary and mint, from a spray I instructed the cleaning lady to spritz in the air and on the chairs and couches. The living room is furnished in what I would call modern-but-not-statement: a curved sectional with tapered legs, an Eames chair, a cowhide ottoman. There is also some art.

My husband is Jonas Eklund the sculptor, and he is well-known in certain circles. He sells two or three pieces a year, which, for a working artist, is considered very successful. He also has pieces in the permanent collections of the Whitney and the Tate. If you are not familiar with these circles, you might think this success pays for our lifestyle significantly. I would say instead he contributes in a quaint way to our household income.

I walk through the kitchen, which is an open plan and was a nightmare of renovation (how many mistakes, how much half-assery, can one contractor commit? the answer is a lot) but now is so beautiful with the white quartzite countertops and mosaic marble backsplash imported from Italy that I barely think of that dark time when plaster chunks covered the floor and every surface was wet and gluey. Now I just want to touch everything.

I didn’t grow up poor but I didn’t have much, so now I truly take nothing for granted. I believe there is nothing wrong with relishing the bougie-ness I’ve worked my whole life for. I don’t practice any kind of organized religion, so I will pray at the altar of my Bosch oven and anoint myself with a single dot of Amber Aoud behind each ear. Through the kitchen windows, I see my husband sitting on the deck, wearing his summer uniform: white drawstring wide-leg pajama pants, no shirt. His hair, still more blond than gray even though he’s five years my senior, is wet from his daily swim and shower at the Y. He is striking even when he doesn’t try to be, tall and tan and lean and looks every inch a Swede, which he is. Effortlessly hot. Women fall at his feet and always have. I had to step over quite a few to get to him.

I slide the glass door open and step onto the deck, and Jonas looks up from his phone and his small paper cup of espresso, one corner of his mouth pinched in a smile.

“Your new patient ended early, Doctor?”

It’s a joke in our family-everyone calls me Doctor. It started with Jonas teasing me whenever I curbed toward bossiness, and then the boys picked up on it when they were little. Now we have a selection of stories to tell at functions and events, such as when our oldest, Elias, was in kindergarten and insisted that the second Sunday in May was actually called “Doctor’s Day.”

“Yes,” I say, sitting in the chair opposite Jonas at the patio table. “He was a little something different.”

“Ah,” says Jonas, not listening. His smile grows as he views the screen on his phone. Then he hands it to me. “Elias is doing tennis again.”

I scroll through the pictures. Both of our sons are at sleepaway camp in Vermont for four weeks. We give the people who run the camp thousands of dollars, and in return they send us a steady stream of pictures of our kids doing fun things.

Elias is thirteen and looks and acts like Jonas. He had his first girlfriend at age nine. In the photos, he is smirking as he waits for the ball in a neutral stance, long limbs sprouting out from his white shirt and shorts, blond hair falling over one eye.

“Any of Theo?” I ask. “Oh yes, keep looking.”

I swipe until I see our younger. Theo is eleven, tall and blond like his brother and his father, but emotionally more like I was as a child: forever analyzing and therefore a little nervous. But I figured out how to balance the two, and I have confidence he will as well. It just may take some time.

In Theo’s pictures he is holding a small clay coil pot in one hand and a wire-head loop tool in the other. He’s concentrating hard. I zoom in on the pot.

“Those coils are a mess,” I say.

Jonas sips his espresso, says, “I didn’t see.” I flip the phone around so he can see.

He lets out a snort of laughter. “He’ll fix it up,” he says.

“If you say so.”

I place the phone on the table and slide it to him. “What are your plans for the day?”

He stretches his arms behind his head. “Studio for some time. Then David Layton has an opening-signing thing at Sapirstein in West Chelsea.”

My husband goes to one or two exhibition openings a week. Sometimes he knows the artist, and sometimes he doesn’t. He says he goes to support his friends and also meet potential buyers. “Art is connection,” he has said, in every meaning the words can have. Of course I believe him, but I know he also likes to go and drink cheap rose and flirt with twenty-five-year-olds. And that is fine, too. I know who I have married, and he knows me. Considering how many of my patients come in and whine about the lack of understanding in their relationships, I have come to see it as a rare thing.

We talk for a minute more and then look at things on our phones. I pull up Nelson Schack’s intake form he’d emailed ahead of time. His address is not far from mine, in Sunset Park. I check to see that his deposit hasn’t budged on Venmo. I google him, but there is a Peruvian economist with the same name and he takes up all the search space.

I think about calling the police.

I’ve actually never had to do it before. I’ve heard countless musings of suicidal ideation and homicidal fantasies-I would argue these are normal. The urge to not have to wake up at five forty-five and go to work every day and live in your pesky body with all its aches and flabbiness is strong for most people at least some of the time. Or fantasies about your ex-wife dying-maybe it’s by your hand or maybe she gets hit by the street sweeper on the way to her candle-dipping class or whatever. Normal.

As it turns out, I’m guilty of a little narrative omission myself, you see—next to the big red line on my bathroom scale indicating a necessary breach of doctor-patient privilege, there are actually three skinnier rosy pink lines: the expressed thought that a patient wants to harm himself or another specific person (“I want to kill my mother”), an articulated plan to commit the act (‘Tm going to kill my mother by poisoning her tea”), and obvious intent (“I’m intending to kill my mother by poisoning her tea tonight”). If you tell me anything like that, I would have to make a call.

But nothing so detailed from Nelson Schack.

So I forget about him. My job takes total compartmentalized focus. If you’re on my couch (or in my swivel chair), you have my attention.

I go back downstairs to fluff the pillows for Charlotte. She is five minutes late and complaining about the CVS pharmacy line that caused her to be late (she would never actually apologize for being late, you see), and drinking from a gallon jug of water with motivational messaging printed at every eight-ounce-mark (“You’ve Got This-Keep Chugging!”). But her hour starts and passes, and I don’t get anything new from her in this session except that she thinks she might have a UTI but hasn’t had it checked out; apparently she’s been meaning to find a new ob-gyn because her current lady has “weird alien fingers.”

Charlotte leaves, and next is Sad Sober Rahul. Still sober, always sad. Every time I see him we talk about meds, how they might change things for him, how we could start on the lowest dose, but Rahul is adamant about being on nothing, no drugs, no meds. Doesn’t even take a multivitamin. I find his commitment admirable, but there comes a time when you can say, I think today I would not like to be so miserable.

After Rahul we have Amanda Demanda. What does Amanda Demanda do? you wonder. Well, she demands. And asks, and pleads, and whines: Why can’t things be easier? Why is it all uphill, why does it feel like I never get picked first for kickball?

Funny thing, she has valid reasons to ask these questions. She’s had some tragedies, some loss, some pain like most of us, and, hell, after the last year we can probably expand that “most” to “all.” But you have to do more than simply demand, more than give your desire a name and admit you’re angry or sad. It’s the same for all of us, now more than ever—our demands, our prayers, our pleas-they’re nothing, as weightless and invisible as the cotton-candy-scented smoke from the vape twins’ pens. So I try to impress upon her in the kindest and gentlest of ways, your hope should not be that conditions improve but that you find the strength to meet your own demandas, dear Amanda.

After Amanda, I run upstairs to grab a snack of grapes and almonds and then hurry back down for Dig Doug. Doug works for the Parks Department and is still in the mire of grieving his brother, who died when they were kids. He rarely indulges in self-pity. I’m not a neurologist (though I knew quite a few in school and, boy, are they a quirky bunch), but I believe that when someone is grieving for so long, the pathways of sorrow are burned in the brain so deeply it’s nearly impossible to pull him out. I’ve tried all the thought-pattern tricks, pulled every cognitive behavioral rabbit out of my shrink hat—nothing has stuck for poor Doug. But still he shows up, so then, so will I.

My day would not be complete without a weeper. Today it’s Weepy Jasmine. She does not get a more creative name because if you met her at a party or worked with her (she’s a middle school teacher, God help her students), your only takeaway from the interaction would be that she cries at everything. When she’s happy, when she’s sad, when she’s angry, when she thinks something is hilarious. She has spent whole hours with me barely getting words out past her sobs. I nod and hand her the tissue box, which she cradles on her lap like a sick cat. She pays me my rate whether or not she speaks, so she can spend her hour however she chooses.

This is when people think being a mental health professional is easy—I could listen to someone cry for an hour, you think. I give my girlfriends good breakup advice and was really nice to that guy I met on the ski lift that time.

Let me tell you something: It takes a particular sort of person, not to mention years of studying and practice, to be able to listen. Just listen. Just be in the room and not share anything from your own life or offer a suggestion, to actively listen to another human being be is nearly impossible for an average person to do. As I’ve said, I did a ton of work with a more acutely disturbed section of the population, people who score literally off the chart on the Psychopathy Checklist, who would have exploded the bathroom scale in my analogy to bits with all the dark shit they thought and said. Do these people ever get better? Some, maybe. With a lot of coaching and a lot of meds, maybe a couple of days a week they don’t feel as stabby as they do the rest of the time. In the end, though, when it came time for me to build my practice, I chose the people who just needed someone to actually hear them.

And who could cover my full fee before hitting their out-of-network deductible.

After Jasmine’s hour, as is my habit every time she leaves, I empty all the discarded tissues from the small wastebasket. I dump them, like a flock of flightless snot-ridden birds, into the larger garbage can in the kitchen, and then my door chimes, and I’m taken aback.

My last appointment, Bambi Ben, isn’t due for another hour. Ben is a wisp of a fellow, gay and southern, with the dewiest doe eyes you’ve ever seen. He’s different from most of my patients because I think he is actually interested in change, committed to the work of being happier. He brings a large coffee to our sessions and will take notes, gliding over the traumas of his gay southern childhood as things that happened and were terrible but are over now. I sometimes wish I could drag him in front of my other patients and say, You see? It’s possible. You don’t have to move on but you can move forward.

But Ben never gets the time wrong and is never this early.

I go to the front door and squint through the peephole and see two strangers standing there. I open the door, and they show me their badges.

Then we begin.

__________________________________