A creature who was once a scientist lurches out of the moonlit mire to peer into the lantern-bright windows of a Gothic manse, where the woman he loves thinks him dead, and the villain who killed him holds her close. “What is a memory?” the woman sobs, lamenting her lost love. “It is the gaping wound that once had been your heart—when you learn you are alone…”

Beyond the window, the monster—hunched, hulking, green—looks on, helpless. Red eyes incapable of tears, he remembers…

From his first appearance in 1971 in DC’s House of Secrets #92, Len Wein and Berni Wrightson’s Swamp Thing seemed doomed to be the monster lurking beyond the darkened pane.

By the time Swamp Thing #1 hit spinner racks a year later, Wein and Wrightson’s series had revamped and fleshed out the story of Dr. Alec Holland, a research scientist murdered, along with his wife, for his “bio-restorative formula.” Horribly burned in an explosion that destroys his lab, Holland flees into the swamp, where he succumbs to his injuries, only to be miraculously reborn from the bog, “a muck-encrusted, shambling mockery of life.”

It was this tragic outsider status that Alan Moore would nurture and tend when he took over the fledgling Saga of Swamp Thing in 1984, swooping in to save the green giant from the brink of cancellation. For Moore, the character presented a unique opportunity to tell sophisticated stories about love and loss and memory, stories that sprang from a rich topsoil sewn with fairy tales and myth—and beneath these, the deeper, darker earth of horror, where things we’d rather not see turn and tunnel from the light.

Below is a triptych of my favorite stories from Moore’s definitive run. These tales do what I love best in horror: they borrow from a multitude of genres—crime, fantasy, fairy tales, science fiction—in order to show us nothing so terrible as our own sad reflections in the glass. Startled by the red eyes peering back, we remember who we are—and wish, perhaps, like all monsters, we could forget.

“The Burial”

“The Burial” is a ghost story, in which the ghost of Wein and Wrightson’s 1972 Swamp Thing (pictured left) haunts Alan Moore’s 1984 Swamp Thing (pictured right). It’s a clever way to not only retell but reshape the creature’s origins.

In “The Burial,” Alec Holland’s ghost draws Swamp Thing through the woods, back to the site of the laboratory, and Moore begins his run in much the same way the creature first appeared in House of Secrets: with Swamp Thing lurking at the edge of a life he can no longer live. Ghosts are memories, memories are ghosts, and Swamp Thing is forced to watch, helpless, as Holland and wife Linda share a smile, a laugh, a kiss before dying again, Holland plunging into the bayou engulfed in flames. Swamp Thing sits in the shadow of the decrepit laboratory. He waits. He watches. At last, he sees himself, green and dripping and born anew, emerge from the swamp. Swamp Thing ’84 and Swamp Thing ’72 now stand face to face, the former wanting to speak, to understand, the latter only pointing mutely at the bog before disappearing. Pointing at the last resting place of Alec Holland. After Swamp Thing exhumes Holland’s bones from the muck of the bayou, in a panel both triumphant and heartbreaking, he cradles Holland’s skull and wonders, “…Down here…in the cold…all those…dark years…you must…have been…lonely….” And then, laying his own origins to rest, he buries Alec Holland’s bones.

“Down Amongst the Dead Men”

Death and burial and resurrection are perennial themes in Moore’s weird fairy tales. Among the weirdest is “Down Amongst the Dead Men,” wherein Swamp Thing must descend, Orpheus-like, into hell to rescue the soul of the woman he loves, while her body remains earthbound. The body belongs to Abigail Cable, nee Arcane, the niece of an old warlock who once, in the Wein/Wrightson years, tried to transplant his own twisted, evil soul into Swamp Thing’s body.

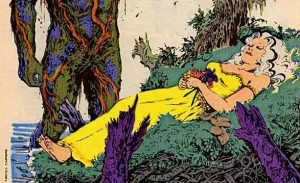

“Dead Men” opens with a dramatic Bissette and Totleben splash page of a grief stricken, root-gnarled Swamp Thing standing over Abigail’s corpse, which reclines on a bed of moss and vine in peaceful, Sleeping Beauty repose (how she got this way is too complicated to explain here; see previous issues). In this story, through his determination to save the woman he loves, Swamp Thing’s powers are extended to the realms of the dead.

On his way to hell, he passes through a verdant woodland, an “aspect of heaven,” he’s told by his guide. There, he encounters the shade of Alec Holland, who thanks him for the burial of his bones (see “The Burial”), and invites Swamp Thing to meet Linda, his wife. We see her from afar, lit in a shaft of heavenly light, followed by a close-up panel on the creature’s red, alien eye. Linda’s reflection in it, a stark reminder: this life, that love, have long since passed our hero by. Once again, even among the dead, he is out of place.

Eventually, Swamp Thing passes through the Gates of Hell and fights his way through all manner of Lovecraftian nightmares, monsters “that would tear the wings from angels” out of boredom, we’re told. Ultimately, he triumphs in battle with his old enemy Arcane, bringing Abigail’s soul out of infinite chaos, and in a final, lyrical flourish, typical of Moore’s work (and a callback to that original House of Secrets appearance, in which the creature is incapable of shedding a single tear for the life he’s lost), Abigail wakes to falling snow in the Louisiana swamp, and the revelation that her savior is crying.

“Rite of Spring”

It can’t be easy, falling in love with a vegetable. Especially not one whose own humanity is, at best, defined as a tragic need to remember things you’d rather forget. And yet: Abigail Cable becomes Beauty to Swamp Thing’s Beast, touching deeply that empty green space where a man’s heart used to beat. In “Rite of Spring,” Moore gives us the consummation of this romance. It’s the trippiest sex in all of comics. It’s also beautiful.

After she confesses her love to the befuddled creature, Abby and Swamp Thing share a kiss that tastes, to her, of lime. As the two stroll hand in hand, Abigail insists the physical act of love is not so important, but a frustrated Swamp Thing says there should be “communion.” He then wades into a pond and sprouts a yam-colored tuber from his chest, which detaches with an evocative POK! Hesitant, Abby tastes it at his urging, and the panels that follow privilege her point of view, setting the boundaries for how we, the readers, will experience what follows, as the world melts away in a cacophony of color.

A blazing sun seems to radiate from Swamp Thing’s center. We enter his consciousness with Abby, see his perceptions of the Green. What are those little lights that drift inside him, like stars, she wants to know. “Insects,” he tells her. Everything in the world is alive, and it’s all made from the same luminescent strands of silk. We turn the book in our hands as Abigail’s world literally slews sideways, and suddenly we’re reading vertically, a great intertwining wash of life and color, salamander, catfish, dragonflies. Birds and rats and the copper taste of blood and “the pulse within the world,” claws and spiders and a savage tide and the whole of it framed between great red orbs crackling with energy—

And then we’re back. A little sweaty, a little shy. Swamp Thing and Abigail Cable, sharing a post-coital embrace, as butterflies dine on half a yam, broken in the grass, and flowers spring from the monster’s back.

And so we move from “Burial” to “Dead Men” to “Rite of Spring,” but death and rebirth are hardly the only arcs we could have traced. If I had a few thousand more words, I’d talk about elementals and werewolves and fish-vampires and that “blue-collar warlock” John Constantine, but we have to end it here, with Moore’s monster at the edge of a new threshold, reimagined from Wein and Wrightson’s creation: a Swamp Thing once doomed to remember its own humanity puts those memories to rest like bones, and he who could not cry now sheds tears that bring the snow. Any new memories the creature makes will be his own, no one else’s.