“I gave her my ugliness.” This is what I said to my editor when we first spoke about El, the protagonist of my debut novel Man’s Best Friend. El’s issues—her selfishness, her unavailability—were very much my issues in my early twenties. I was the friend who dodged phone calls, the employee who might not make it in on Monday, the girlfriend of questionable loyalty. In my attempt to be no one to anyone, to outrun the potential for abandonment, I hurt the people in my life, myself most of all. El is much more destructive than I was: my own misadventures were hardly pulse-pounding. I walked so El could run, deep into her darkness. She was never written to be aspirational.

Novels about destructive women have always been my favorites. In the lead up to the release of Man’s Best Friend, I’ve been thinking about fiction in this tradition, and wondering why it is that problematic female protagonists inspire such love/hate reactions from readers, why I fall so firmly on the love side. I had my theories, but I decided to start by looking at the science.

Women are, surprise surprise, the safer sex. “Few… have examined gender as a potential moderator of the emotional dysregulation associated with violence,” one study points out, though it asserts that men are more likely to exhibit violent behavior than women. Another study confirms that women “more rarely and/or less intensely” behave in a self-destructive manner than men i.e. are less likely to binge drink or drive recklessly. What these studies could not answer for me is why women cause less harm, on average, than men. It’s a question of nature or nurture: are women less destructive because of some genetic predisposition, or because we’re coached into compliance?

[A]re women less destructive because of some genetic predisposition, or because we’re coached into compliance?When I read novels that center destructive women I feel a pulse beneath the words, a dark song of repressed despair that resonates in my body. If women ruminate on the harmful and the selfish, if the darkness is within us, can we really chalk it up to evolution that it’s less likely to express itself outwardly? Much more convincing to me is the idea that, within the confines of the patriarchy, women behave in accordance with cultural expectation because it’s the only way to be acceptable, likeable, loveable. This goes doubly for women of color, who are saddled not only with the burden of patriarchy but of white supremacy, too. As Raven Leilani has said, “Unlikeablility is a very different thing to navigate for Black women… What we call unlikeability in white women, I think Black women feel, but have to suppress in order to survive.” Yes, there are many excellent novels by women of color with unlikeable or destructive female protagonists, Leilani’s Luster among them, but I doubt anyone would argue that women of color author and successfully publish such novels more than white women do. All this to say, it’s my belief that oppressive social constructs are deeply entangled with women’s decreased potentiality for destruction, self-centered or otherwise, and thus the destructive woman on the page (particularly if she isn’t white) feels transgressive—and, for some readers, unsettling and unwelcome.

On Goodreads or Bookstagram, critiques of harmful female protagonists aren’t often fleshed out. You’ll see something like: insufferable whiny DNF’d at 15% or I’m all for a complicated MC but this?? Sometimes, though, the takes are sweeping, full of observations about how “unhinged” characters are all well and good, but this character felt unhinged for unhinged’s sake. Don’t even get me started on the readers who rate American Psycho five stars but need their destructive women to have some spelled out tragic #MeToo or capital T trauma backstory to justify their wrongdoing.

And then there are those readers like myself, who love a destructive female protagonist. It would be nice if this were a reflection of progressive values, but really it’s just my taste, informed, I suppose, by my own life experience. It’s taken a lot of time and effort to cultivate compassion for my past self, the twenty-two year old whose abandonment issues and untreated alcoholism made her a not so great roommate, daughter, friend. When I see pieces of my self-destructive past glimmering like shards of glass through someone else’s prose, I feel a certain comfort, a gratitude that I’m not in that broken place anymore. And even when I don’t identify, even when I confront a violent and irredeemable protagonist who I don’t love but love to hate, I am riveted by the author’s transgressive act in portraying such a woman.

I present to you now a list of excellent novels about destructive women. These authors use the page to liberate woman from the constraints of culture, allowing her to be what is not allowed or not anticipated, and in doing so don’t condone harm but expand our understanding of the human condition.

Pizza Girl by Jean Kyoung Frazier

One of my favorite reads in recent years, this novel tells the story of Jane, a pregnant 18-year old pizza joint employee who becomes obsessed with a female customer. Jane neglects every caring person in her life as well as her unborn child (she drinks throughout her pregnancy), instead focusing her attention and empathy on the customer. The sophistication of Frazier’s narration is especially impressive; she has a gift for demystifying Jane for the reader while allowing Jane to remain eighteen, barely adult, a mystery to herself.

Wideacre by Philippa Gregory

Back in the mid-2000s everyone read The Other Boleyn Girl in anticipation of the Natalie Portman/Scarlett Johanssen feature adaptation, but Wideacre is Gregory’s debut novel. The protagonist is a squire’s daughter, Beatrice Lacey, and she is queen of the Faustian bargain. I won’t spoil all the twists and turns, but be forewarned: nothing taboo is off the table in this novel. Beatrice graduates from one heinous act to the next, all to keep hold of her beloved land, the locus of her identity.

The Pisces by Melissa Broder

Lucy, a PhD student reeling from a break-up, moves to Venice Beach for the summer and, while coming to terms with her love addiction, becomes infatuated with a merman. The vulnerability of this protagonist is so acute it will no doubt inspire skin-crawling discomfort for those who haven’t become acquainted with their shadow selves. I love this book: you might, too, if descriptions of U.T.I.s after hotel bathroom anal sex are your thing.

My Men by Victoria Kielland (translated by Damion Searls)

The torrent of stunning prose in this novel is almost as violent as the protagonist, Belle, herself. Belle Gunness was a real-life American (Norwegian-born) serial killer. In Kielland’s telling, Belle’s darkness incubated for a long time before she graduated to murder. When Belle’s behavior does escalate, Kielland draws us into Belle’s confusion: “The face the mirror, which image should she believe in?” Kielland paints her protagonist with such a human brush that the ending, where we learn the unspeakable horror Belle is responsible for, gives the reader a taste of serious whiplash. I dare anyone with a little life experience not to relate to this passage: “[I]t really hurt to love, it was like being skinned alive, and yet everyone took every chance they could get, every time. Full-grown adults, it was absolutely insane.”

I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel

In the immortal words of David Fincher, “I like characters who don’t change, who don’t learn from their mistakes.” In her debut, Patel’s first person (unnamed) narrator shares one damning insight after another about the age of social media, white privilege and sexual power dynamics, but while she confesses her personal missteps in full, all her powers of insight don’t save her, in the end, from the kind of delusional thinking that got her into trouble in the first place. Many readers have been and will continue to be hooked by the premise of I’m A Fan—a young woman, infatuated with a married man, online stalks his more prized mistress—but the book is so much more than a pulpy premise. For me, Patel achieves the thing all storytellers aim for, creating the universal within the specific, mirroring back to her reader the prison we create for ourselves when, as creatures of capitalism, we harm ourselves and others in pursuit of a life that only looks Good and Right.

The Guest by Emma Cline

The guest of The Guest is Alex, a twenty-two year old sex worker who has conned her way into a relationship with Simon, an older guy, and the owner of a sumptuous Hamptons summer home. But after a dinner party faux pas Alex is exiled from Eden, and for the rest of the novel she’s in survival mode, counting the days until she can see Simon again, using anyone and everyone in her path so she can remain in the Hamptons, away from New York City and Dom, a dangerous man she’s stolen from. Each of Alex’s victims is such a desperate character (an uptight house manager is a secret cokehead; a rich young woman, a literal member of the club, has no friends) that Cline distracts us, for most of the narrative, from Alex’s psychological desperation. The reader is put in the same position as Alex herself, who’s held her emotions at a distance for a long time. Cline doesn’t use Alex’s hidden fragility to excuse her bad behavior, nor does she force Alex into an ethical makeover after some dark night of the soul: redemption is not necessary because Alex is no hero.

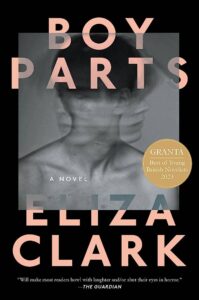

Boy Parts by Eliza Clark

Irina, the protagonist of Boy Parts, initially comes across like a version of Lisbeth Salander, a sharp, incisive and hard to know bisexual woman with obscure taste. She’s revealed, however, to be someone Lisbeth might target, a sexual sadist harboring a deep dark secret. Clark assigns Irina problems that haunt many women, including an eating disorder and more than one experience of sexual assault. Irina grapples for control behind the camera, photographing men, the would-be predators, just as she seeks control around her appetite, planning to vomit whenever she consumes something apart from bagged salad. Readers who struggle with the problematic female protagonist will no doubt stumble (among other things) over Irina’s poor treatment of her closest friend, but it’s this relationship that really allowed me to fall in love with this book. This is not simply, as some have suggested, a “female” American Psycho: it read to me like a story about one woman’s profound struggle with attachment—attachment to love, attachment to success, attachment to reality.

Luster by Raven Leilani

Some might take issue with Edie’s inclusion in the destructive female protagonist tradition, because Edie is not all that hard to love, ultimately. This is a main character who does graduate to a more mature perspective in the end (literally as well as figuratively—her painting improves over the course of the novel). That said, Edie’s behavior in the early chapters of Luster is problematic and frustrating, and in my view firmly cements her in the transgressive canon. A Black woman in her early twenties, Edie is fired from her publishing job for inappropriate sexual behavior. She’s been involved with so many colleagues, men and women, she’s not even sure who brought her behavior to the attention of HR. Edie compares herself unfavorably to another Black female colleague: “She plays the game well… She is Black and dogged and inoffensive… I’d like to think the reason I’m not more dogged is because I know better, but sometimes I look at her and I wonder if the problem isn’t her but me. Maybe the problem is that I’m weak and overly sensitive. Maybe the problem is that I am an office slut.”

Leilani’s choice to have Edie address us in the first person present makes the narration inherently unreliable, so we don’t know, after this admission of Edie’s, how much we should forgive and how much we should judge. Should we be understanding that Edie is not more dogged? Should we think she’s weak? Both, I think. Most of the novel is the story of Edie’s entanglement with Eric, an older, alcoholic white man, and how she comes to move in with Eric and his wife, Rebecca, and their adoptive daughter Akila. Edie’s sexual relationship with Eric is fine by Rebecca until it is not, at which point Edie carries on with Eric anyway, for a time. More interesting than this, however, is the fact that Edie allows, even encourages, Eric to hurt her, hit her. At a certain point, Eric leaves Edie a remorseful, drunk voicemail saying something about how he knows she’s a human being. It’s not terribly relevant whether Eric knows this or not—the only relevant question is whether Edie knows who she is, what she deserves. Will I continue in this pattern of destruction, or won’t I? These are the worthy stakes of this novel.

***