This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Dreams are one of those things professors and editors and more seasoned writers all tell you not to write about. It’s a day-one “don’t,” right up there with adverbs and any speaker tag other than “said.” It’s willfully unrealistic to write characters who don’t dream, but dreams in fiction often function as a clumsy storytelling shortcut. Consider the “false start,” when a character wakes up from a dream the reader didn’t know they were having on page two or three, flustered by the subconscious irruption of whatever past trauma drives the story. We dislike this trope because it’s lazy, low-hanging narrative fruit.

All literary creatures are hypersensitive to symbolism, forever fighting the Freudian impulse to assign meaning to things that are intrinsically meaningless—like the color of the curtains or what the weather is doing on the other side of that window. Real-life dreams resist interpretation; even the scientists who study them can’t say where they come from or what physiological purpose they serve. So why are they irresistible to young writers trying to make their work mean something?

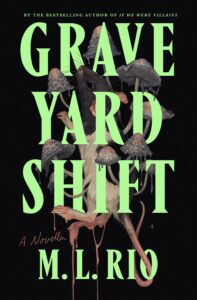

I’ve grappled with severe insomnia my whole life. Long nights of no sleep were how and when and why I learned to write. I couldn’t dream the way most people did, so I dreamed up whole novels instead. Most of my fiction is still written in a weird, dreamlike state. My first novella, Graveyard Shift, which unfolds over one sleepless night, pushed me to think more deeply about the role this dream state plays in my writing. On the rare nights I do sleep enough to dream, characters from whatever novel I’m working on often appear in starring roles. Writing is the last thing I do before bed, so they’re closer to the surface of my subconscious than the real humans I interact with each day.

One nocturnal encounter stands out: I crouch under an overturned boat in a dry lakebed, knee to knee with the troubled main character of my novel. We dig in the sand between us with small plastic shovels, slowly uncovering a bottomless burial ground for single, mismatched children’s shoes. The book had nothing to do with shoes, children, or boats, but for some reason my troubled brain manifested a version of the famously unsettling six-word story “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.” I still think about it six years later.

Asking myself why that was, I realized that what makes a dream a bad plot device is also what makes it an excellent writing prompt. We’re wired to look for meaning in everything, and we will—like Jane Eyre’s action—make it when we cannot find it. The books that stick with me as long as that dream are books with blank spaces begging to be filled in. A story that refuses to hand us all the answers demands we do some interpretative work of our own and precludes a passive reading experience.

We rarely recall the beginning or end of a dream—how you got under that boat or what happened when you crawled out—so the details we can grasp in the moment take on an outsize significance. We make whole tapestries of meaning from a few evocative details. A novel done well does this, too: it offers detail, concrete and specific as lost shoes in the sand, but lets us connect the emotional dots and draw our own conclusions. No need for ham-fisted symbolism or fictive psychoanalysis.

Usually, you don’t notice you’re in a dream while it’s happening—so seamlessly immersed that you can lose yourself there for a while, and not notice how time is passing. That’s the same feeling I’m always chasing in fiction: nuance and mystery inseparably intertwined. Not a clinician, but a weaver of dreams.

_____________________________________________

Graveyard Shift by M. L. Rio is available now via Flatiron Books.