I learned about Madame Stephanie St. Clair by a stroke of luck. During my first trip to New York City, I had to see about the Museum of the American Gangster. It’s in a former speakeasy, so like the true rube that I was, I walked past it on St. Marks three times before I clocked it. Madame St. Clair’s history was even more elusive.

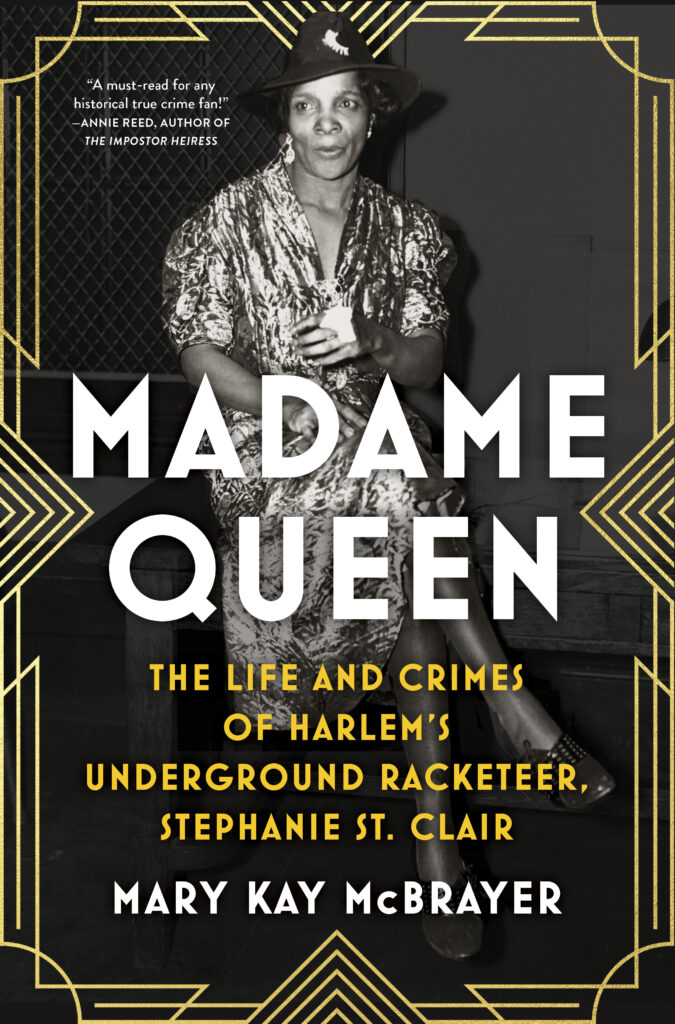

Her photo hung inside the private museum alongside big-name gangsters from the ’20s and ’30s, like Al Capone, Lucky Luciano, and Dutch Schultz. Theirs were mug shots. Hers was the black- and- white equivalent of a thirst trap selfie: this stunner was on the edge of someone’s writing desk in a sparkling dress, legs crossed at the knee, and gorgeous mule pumps slipped over her silk-stockinged feet. She looked away from the camera, midspeech, her left hand, mysteriously bandaged, about to gesture a directive to someone just out of frame. She was the only woman on that wall, and she was one of about three persons of color (Bumpy Johnson and Frank Lucas were pictured, although I later learned that those guys were her direct descendants, criminally speaking). When I tipped the docent after the tour, I asked her to tell me everything she knew about Stephanie St. Clair.

She took my money and smiled and said, “I just did.”

If I’d gotten a fuller answer from her, this book might not exist. As a naturally defiant person, I took that docent’s hard “no” as a “try harder.” The first few internet searches yielded equally captivating images of St. Clair, posing hands on hips in a turban and a fur-collared wrap coat. I could never make out what animal her furs were from, but I always imagined them to be wolf.

A little deeper into my research, and I unearthed the reason why she’d taken those photos at all: in the early 1930s, after her numbers racket boomed and got the attention of both organized criminals and corrupt police officials alike, she took out ad space in the local Harlem paper, the Amsterdam News. That’s where she wrote open letters to judges, mayors, and her neighbors, not only defending her honor, but citing specific advice, like what to do when the police tried to search your home without a warrant, or even how to report badge numbers from the cops who did that. She basically created her own PR campaign. After learning all this, I was deeply invested, and I tapped every research vein I could think of: I accessed archival articles through the university system library where I taught as a limited-term English professor; New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center; and the special collections down the street from my house in Atlanta at Clark, Morehouse, and Spelman. I bought out- of- print books about Harlem in the 1920s and ’30s from secondhand websites on the off chance she might be mentioned in a chapter or two. I scoured the (auto)biographies of her contemporaries, even fictional representations of the time and place, just hoping to catch a glimpse of her. But even with all that effort, information about her remains scant. She was absolutely glamorous. She was a philanthropist. She was a West Indian immigrant, a woman who bootstrapped herself into success in spite of the odds. A folk hero. A genius. All these things are true. And so are the facts that she was a businesswoman, and her business was illegal. Let me clarify: she was firstly a business woman, not a criminal, but because her business happened to be criminal, she had to engage with criminals. Like the adage goes, when you hang around shit, you get shit on you. The criminals she had to deal with were no small potatoes. They were those infamous villains whose names are still known, whose mug shots hung in the museum.

The more I learned about her, the more enthralled I became, the more I wondered, Why had I never heard of this woman before? I love gangster shit. Fictional and historical alike, I like to think I’m pretty well- versed in the lore. I may not know the details of every criminal’s home life or the nuance of their relationship with their parents, but usually their names at least ring a bell. So, to my question above, Why had I never heard of her? I drew the obvious answers. Racism. And sexism.

For sure, those are huge impediments to getting credit where it’s due, but Madame St. Clair was different from her contemporaries. The criminal nature of her gambling racket was incidental. That’s not the case with other gangsters. Many of them were criminals by trade, too mean or too mouthy to work a regular job, and they almost always wanted you to know their name. They wanted that clout, and that’s ultimately what brought them down— their own mouths. Or, on a long enough timeline, someone else would rat them out.

When I ran out of things Madame Queen said about herself, I had to go to what other people said about her. It was other people who started calling Stephanie St. Clair “Madame Queen” in the first place. Once in a while, she appears on a list of donors to a particular cause. She has a cameo in Dutch Schultz’s story written by his lawyer Dixie Davis, which I include in these pages. Her “world” is represented in Shirley Stewart’s book, The World of Stephanie St. Clair: An Entrepreneur, Race Woman and Outlaw in Early Twentieth Century Harlem. She has a paragraph in Selwyn Raab’s compendium Five Families. She’s also a peripheral character in the Francis Ford Coppola movie The Cotton Club and Hoodlum starring Laurence Fishburne— but no one points the lens right at her, even though she was the only illegal business owner who didn’t get burned by her own game. (She did get burned, but more on that later.)

This book is my attempt to fill the void of her presence. When I couldn’t find credible references to tell the story, I took some intuitive leaps based on adjacent research. The narrative opens at her business’s height, featuring one of the advertisements she placed in the Amsterdam News. I like to think of that article as her debut: when the police she’d been icing for years decided she was too successful, and they needed a bigger slice of her pie, she turned the tables by announcing she had paid them bribes. From there, we retrace her steps from the first evidence of her existence in Guadeloupe, when she immigrated to the States in steerage on a cargo ship, which is also her first PR spin. She was thirteen at the time, accord-ing to birth records, but the ship’s muster records her age as twenty- three. Do I know for sure that she lied on purpose? No. But after learning all I could about her and her character, I can deduce that as the most accurate explanation for the discrepancy.

And that happens often in St. Clair’s story, that ambiguity between intentional discrepancy and discretion.

Madame Queen was good at her job, and she was nothing if not discreet. To be good at a job like hers, you can’t talk about it a lot. You have to be careful what you say, how you say it, and to whom you say it. Sometimes, no matter how much I leaned into a source, no matter how many adjacent narratives I could find, Stephanie was just not there. In those cases, I used the best information I could find to make the likeliest narrative. (I might not be able to prove that’s wolf she’s wearing, but right next to one of her letters is a printed advertisement for a wolf collar, so it was, at least, an option. And look at the striations in the photograph. Is it a printing error? Could be. But do you think it’s likely that she would have identified more with a mink than a wolf?) I will always do my best to distinguish when I have the cold hard facts versus when I’m only pretty sure what happened. Any dialogue that is not verbatim from a source has been reconstructed as authentically as possible with an ear toward the era, region, and character of the speaker.

This book is a work of creative nonfiction. It’s always my intention to tell the truest, fullest story that I can, to really resurrect Madame Queen, because while she might have wanted to fly under the radar during the interwar period, times are changing, and now we can celebrate her for the true boss she was— and I hope to learn more about her, for more of her to surface even if it’s too late to put in this book, because she is so much more than a character on a page.