The sound of gunfire echoed out just as the speaker had finished welcoming his audience with the traditional Muslim greeting “Assalamu alaikum” (“Peace be upon you”). Seconds later, Malcolm X lay dying on the stage of Manhattan’s Audubon Ballroom, his body filled with eight shotgun slugs and another nine bullets from .45 caliber and 9-millimeter guns.

The murder 60 years ago, on February 21, 1965, was a shocking final chapter in the running feud between Malcolm and the Nation of Islam, the Black separatist organization he had helped propel to national prominence before declaring his independence from it. That part of the story — the split, and the fateful palace intrigue that followed — began a year earlier in a most unlikely place: Miami, where, in January 1964, the 38-year-old “Black Muslim” minister had traveled to see if a brash young boxer named Cassius Clay could wrest the heavyweight title from champion Sonny Liston.

At the time, Malcolm had been forbidden by the Nation of Islam to speak publicly, after remarks he had made following President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963. Kennedy’s death, Malcolm had told the press, was blowback from the violence the U.S. had perpetrated throughout the world, an instance of “chickens coming home to roost.” To outsiders, the resulting firestorm over what was interpreted as Malcolm’s glee at the president’s demise had resulted in a rift between Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm. In truth, there was much more to the conflict.

Malcolm recently had learned that Elijah Muhammad had engaged in adultery — and fathered children — with at least three of his secretaries. Stung by Muhammad’s moral hypocrisy, he confronted the Nation of Islam leader and was told, essentially, that such behavior was a prophet’s prerogative. Malcolm reluctantly reconciled himself to that view, but raising the issue had created distance between him and Elijah Muhammad.

There was also Malcolm’s growing discomfort with the Nation’s theology, a combination of Islamic teachings and Black nationalism, with a heavy dose of what some might call science fiction. (Among its core beliefs was that Wallace Fard Muhammad, who founded the religion in Detroit in the early 1930s, would return aboard a spacecraft to extinguish the white race and establish a utopia for his followers.) Most frustratingly for Malcolm, political engagement was not welcome. Malcolm, fueled by his personal disappointment in Elijah Muhammad and by his own expanding consciousness, was moving away from what he would later characterize as the Nation’s “strait jacket” version of Islam and toward Islam “as it is believed in and practiced by the Muslims… in the Holy City of Mecca.”

In early 1964, Malcolm was a man, if not yet at a crossroads, certainly aware one was on the horizon.

He was not the only one wrestling with questions of faith. Cassius Clay first encountered the Nation of Islam on a trip to Chicago as an amateur fighter. Now living in Miami, Clay had begun surrounding himself with fellow adherents and studying the Nation’s teachings in earnest. The only question that remained was when to go public with his membership in the Nation. To do so before the upcoming championship fight — given the Nation’s reputation as a radical organization and the fighter’s cultivated (and already polarizing) image as a show-off — might jeopardize the event. No, Clay grudgingly concluded, better to do it after the fight. Provided he won.

Clay’s initial interest in the Nation had been encouraged by none other than Malcolm. “Malcolm’s thought [was], if we bring in someone who’s a mainstream celebrity, like the next heavyweight champion of the world, we can bring more people into the fold,” explains historian Johnny Smith, co-author (with Randy Roberts) of Blood Brothers, which explores the friendship between the two men.

That, however, was in the beginning, when Malcolm served Elijah Muhammad without reservation. Now that his status within the Nation was in doubt — he was uncertain he would be reinstated when his 90-day suspension expired — he had begun to think differently. Cementing Clay’s allegiance to the Nation might serve to put Malcolm back in Elijah Muhammad’s good graces and even give him leverage to chart a new direction for the Nation. It was also the case that, if Malcolm split from the Nation, being able to take Clay with him would be very advantageous.

If it came down to it, would Clay choose him over Elijah Muhammad? Malcolm hoped his trip to Miami, taken at Clay’s invitation, would produce an answer. Accompanied by his wife and daughters, Malcolm arrived in the city on January 16. It was the day before Clay’s 22nd birthday, and less than six weeks before the fight with Liston.

“There’s all this personal conflict [and] religious conflict stirring inside him,” says Smith.

“Malcolm X, a minister who worked every day of his life, who’s always planning his next move, thinking about his next sermon, his next interview, his next debate, how to organize the Nation; he doesn’t take vacations. But he goes to Miami to hang out by the pool with his kids and this loudmouth boxer? It tells us that, in this moment, he’s a desperate man.”

For the next several weeks, Malcolm remained in Clay’s orbit. Nelson Adams, whose family lived next door to Clay in the Allapattah neighborhood, remembers Malcolm and his father — an elementary school principal, a deacon in the Baptist church, and, according to his son, “a pretty opinionated guy who believed what he believed” — engaging in lively, but “mutually respectful” theological conversations over the fence. Adams, 11 years old then and today a prominent physician in Miami, says there was a feeling “there was something special going on” when Malcolm was around, even if the significance of the visit seemed just out of everyone’s reach.

When, on January 21, Clay went to New York to address a meeting of 1,600 Nation of Islam members at the Rockland Palace, Malcolm went with him. Though he himself was barred from speaking owing to his suspension, he likely would have been gratified to hear Clay tell the crowd that he was “proud to walk the streets of Miami with Malcolm X.” Whatever the Nation’s issues with its most famous minister, Clay seemed to be saying, Malcolm was still his friend. There was reason for Malcolm to hope. Now, if only the fight would go the way he believed it would.

The run-up to a championship fight is filled with both anticipation and speculation. In this case, few gave the challenger much of a chance. Sonny Liston, an ex-con who had worked as a leg-breaker for the mob, wore a perpetual scowl and gave the impression of a man who might knock your teeth in for wishing him a good morning. Liston didn’t defeat his opponents; he dismantled them.

By contrast, at this point in his career, Clay was seen as possessing more flash than substance as a fighter. His hands were fast, but few believed he possessed the punching power, the stamina, or, plainly speaking, the guts to hang with a fighter like Sonny Liston. The kid who spouted doggerel (“If you want to lose your money, be a fool and bet on Sonny!”), promoted himself as “the Greatest,” and, most incongruously for a boxer, was fond of telling everyone how pretty he was? He’d be lucky to last a round. The oddsmakers had him as an 8-1 underdog.

The Nation of Islam was equally skeptical. “Elijah Muhammad and his entourage wanted to keep as far away from Cassius Clay as possible,” recalled the late Malcolm X biographer Manning Marable, in an interview for a 2008 PBS documentary. “They were convinced he would lose. They didn’t want any part of [that].”

Malcolm, though, believed the young man had a destiny to fulfill.

The night of the fight, February 25, Malcolm, sitting prominently in the crowd, watched as Clay entered the ring at the Miami Beach Convention Center and proceeded to do what almost no one expected. Round after round, he peppered Liston with combinations, his lightning-quick reflexes allowing him to avoid the champion’s counters and desperate lunges. By the fourth round, a frustrated Liston, throwing and missing with wild punches, began to tire.

In the fifth round, there was some unexpected intrigue as Clay was temporarily blinded by (depending on who told the story) liniment that had been placed on Liston’s shoulder and had somehow made its way into Clay’s eyes or, more nefariously, a caustic solution used to treat open cuts that had been applied intentionally to Liston’s gloves. No matter. By the end of the round, Clay’s vision had cleared and he picked up where he had left off. When Liston, battered and looking defeated, refused to answer the bell for the seventh round, the fight was over. Clay had, in his words, “Shook up the world!” And Malcolm had won his bet.

Afterward, Malcolm and Clay — with football star Jim Brown and singer Sam Cooke in tow — drove across the causeway to the Hampton House, a Green Book motel popular with Black celebrities, for an impromptu celebration. The most famous image from that night, taken by Life magazine photographer Bob Gomel, shows Malcolm and Clay in the hotel’s café. Surrounded by well-wishers, Clay sits at the café’s counter, lips pursed in a playful smirk. Malcolm, standing behind the counter, raises a camera to his eye to capture Clay in his glory.

Photograph ©1964 Bob Gomel

Photograph ©1964 Bob Gomel

Four days later, Clay publicly embraced the Nation of Islam and announced he would henceforth be known as Cassius X. Malcolm, meanwhile, was already contemplating something like the initiative he would unveil that summer, the Organization of Afro-American Unity, a less dogmatic, more politically-oriented group than the Nation of Islam.

“Speculation,” recounted Marable, “is whirling in Harlem that Malcolm, any day now, is going to be out of the Nation of Islam.” And possibly take Cassius X with him.

To stop such talk in its tracks, Elijah Muhammad made his play, bestowing upon Cassius X the highest honor in the Nation of Islam: an “original name.” Cassius X would be known as Muhammad Ali; Muhammad meaning “worthy of all praise” and Ali meaning “most high,” as Ali explained to a curious television reporter in New York. It was an honor so jealously guarded that Malcolm never received it.

Ali had been drawn to the Nation of Islam out of a desire to find his place in the world, to be seen as a consequential person. Now, he was second in importance only to Elijah Muhammad in the nation’s hierarchy. In Marable’s words, “This [was] checkmate — high-stakes.”

Two days later, Malcolm severed all ties to the Nation of Islam. Ali stayed.

With no one to intercede on his behalf, Malcolm found himself increasingly under threat of violence. On February 12, 1965, his home in East Elmhurst, New York, was firebombed in the middle of the night. Miraculously, no one in the house was hurt, but Malcolm knew his time was coming. “I have been marked for death in the next five days,” Malcolm told his friend and biographer Alex Haley on February 16.

“The Nation of Islam viewed Malcolm as a hypocrite,” says Smith, “[as] someone who falsely declared that they believed in Allah and the messenger of Allah, Elijah Muhammad, and then turned their back on them. They took this very seriously.”

[Three members of the Nation of Islam were convicted of Malcolm’s murder; two were later exonerated. A civil lawsuit filed by Malcolm’s family in November 2024 seeks to implicate the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the New York Police Department in a conspiracy to commit the crime.]

Following Malcolm’s assassination on February 21 (and the suspicious death of his former bodyguard, Leon 4X Ameer, three weeks later), a news crew knocked on Ali’s door in Miami to ask for his reaction. “Malcolm X and anybody else who attacks — who talks about attacking — Elijah Muhammad will die,” Ali offered. “ No man can oppose the messenger of Almighty God verbally or physically and get away with it.” It was a chilling postscript to the friendship he and Malcolm had once shared, and a sentiment that would haunt Ali’s conscience in the years to come as the full impact of Malcolm’s influence on his life registered and he too embraced traditional Islam.

“If we all could predict the future, we would live our lives very differently,” observes Smith. “[But] that’s not how life works; that’s not how history works. ”

Driving through Miami’s ever-changing urban landscape, it is striking to note how much remains of the city Ali and Malcolm inhabited all those years ago: Ali’s house, a modest two-bedroom, is still there; the Hampton House, now a cultural center in which Ali’s old suite, just off the pool, has been preserved for visitors; and the Miami Beach Convention Center, where Ali defeated Sonny Liston and where, afterward, Ali and Malcolm walked out into the night, their dreams glimmering in front of them like so many stars in the sky.

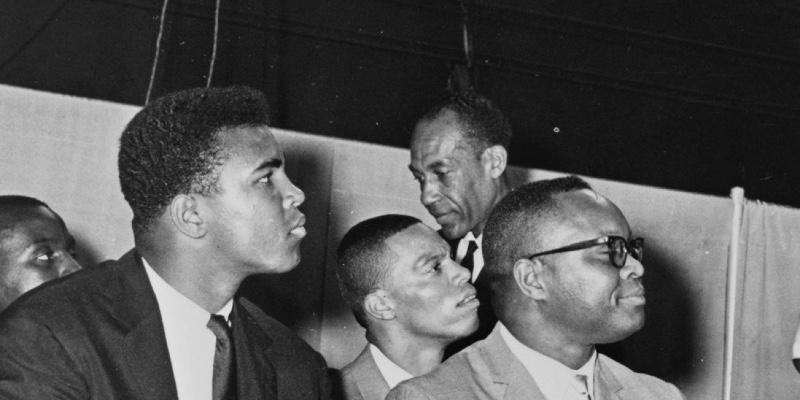

–Featured image: Malcolm X and Cassius Clay, 1964; New York World-Telegram and the Sun staff photographer: Wolfson, Stanley, photographer. / Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection