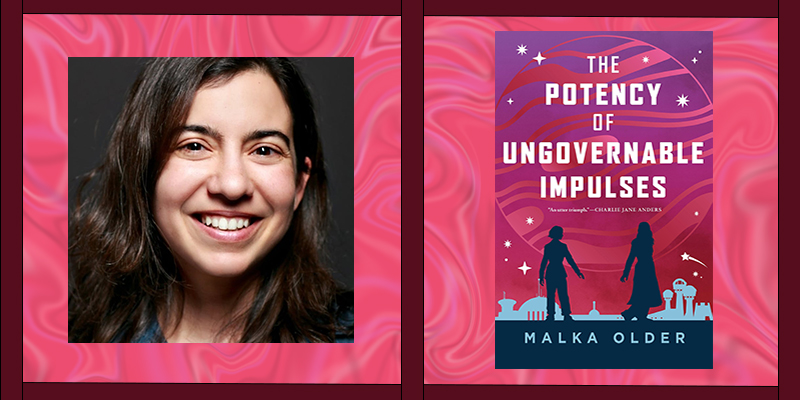

As a writer Malka Older is known for her science fiction series The Centenal Cycle. She is also an aid worker and sociologist, the Executive Director of Global Voices, and a Faculty Associate at Arizona State University. In 2023 she launched a new series, The Investigations of Mossa and Pleiti, which is s science fiction mystery set on Jupiter. It’s also a second chance romance between a police investigator and an academic who in the first book are thrown together years after they broke up.

The third book in the series, The Potency of Ungovernable Impulses, comes out this month and demonstrates what Older has been doing so well, which is to use the mystery form as a way to interrogate and explain the setting. To craft a mystery that is set in a strange alien world but one that is all too human, and where the mysteries are ultimately ones that people have created. There’s a playfulness to the books that comes through despite the dark and complex setting and stories. The books manage to combine mystery, science fiction and romance in ways that make it look easy, even as Older is clearly playing with form and structure, actively trying to make the series not become too familiar.

I spoke with Older recently about why we find the mystery genre a comfort, using genre to explore places and ideas, challenging herself in each book, and writing a mystery without plotting it out.

Alex Dueben: Before we get into your new book, I’m curious about where this series started. Was it the design of the world? Was it the characters?

Malka Older: There were two starting points. A long time ago, I had this sort of “what if” thought that is the beginning of a lot of fiction– and science fiction—which was, how would humans inhabit a gas giant planet? I had this idea of platforms that would be on a ring that was geosynchronous, so it would be revolving. At the same time, I had this idea that people would want to have some interaction with animals and so, there would be this zoo that existed there. That was a long time ago, and it didn’t go anywhere immediately.

Fast forward, it’s 2020, and things are kind of horrible in general. I was reading and rereading all of this stuff that I found really comforting. I started to think about why I find these things comforting and what they are. There were a lot of mysteries on that list. There was romance. There was stuff that was set in academic settings. I thought, the world is like this, and I’m going to take all of the things that I enjoy reading about, and I’m going to write. I did a NaNoWriMo which I just titled “Blank, but make it fun.” I just wanted it to be pleasurable to write and pleasurable to read. I didn’t know at first what I was going to do to get all these disparate elements together. I came back across that note that I had made and it appealed to me. The original note was, some gas giant somewhere. But for me, in this, it had to be more closely connected to Earth. And so it became Jupiter. So to answer your question, it started with the setting. [laughs]

AD: You mentioned that you find mysteries relaxing and many of us find a certain type of mystery relaxing. We love reading and watching British people get murdered in the countryside.

MO: Well, it’s not just British people.

AD: It’s not just British people. We find the murder of all kinds of people comforting.

MO: Yes. We’re equal opportunity. But the British certainly have a good line in people being murdered in small villages or very picturesque places. It is a good question. I’ve asked myself a lot about why I found it comforting. I’ve done a series of Comfort Read Panels with Martha Wells and KJ Charles and T. Kingfisher, who’s Ursula Vernon. Martha Wells is the writer of Murderbot, and there’s a lot of murder in there. We’ve talked about this. One is the traditional, literary analysis answer, which is, something has gone wrong, and it is put to rights by the end of the book. There’s definitely a whole genre of murder mysteries and other detective fiction where things don’t get put right. But in a lot of them, someone’s going to solve the mystery. There’s going to be justice meted out. Or if not, the unknown is going to be revealed.

A lot of times when I read classic detective fiction, even though I enjoy the writing– and I’m thinking particularly here of a couple of Sayers, definitely some of the Sherlock Holmes stories—it’s not actually satisfying as justice at the end. For example, there’s a couple of Sayers—Murder Must Advertise is a good example—where (spoiler), the perpetrator is a really horrible person. But at the end, instead of nabbing this guy, they’re like, we’re going to tip him off and let him get killed as a kind of honorable, suicide. That restores order, because he’s a gentleman, and we can’t just put him in jail. That would be worse. So there’s this other kind of order. That’s also one of the things that I want to kind of push at and interrogate. Which is sometimes tricky on this entirely made up society on Jupiter.

AD: One of the things you do really well is you’re not just crafting a mystery in a science fiction setting, you’re also using the mystery to explore the setting.

MO: I hope so. As I said, I started with the setting. For me, the setting and the characters are really important. I tried not to have the plot drive the setting and the characters, but the other way around. When I start, I don’t know what the full setting is. And so for me, it’s also a way to explore it myself.

AD: So when you say that, you don’t plot out your books before writing?

MO: I don’t. [laughs] It can be very scary, but that’s actually part of the fun of it. I said I’m on Book Four right now and I have some ideas about what’s going to happen, but I don’t actually know yet. I think at this point, I know who the perpetrator is. I know one of the victims. I know there’s going to be another victim, but I don’t know who that is yet. I think I know the motive. But three days ago, I wasn’t even sure of the perpetrator. It’s a process. And it’s a process that involves a lot of editing. It doesn’t mean that the first time running through, I get a beautiful plot that fits together nicely. I also tend to write not completely chronologically. Especially when I’m first starting a book, I’ll jump around a lot in scenes and just put things that feel like they make sense to me. Then as I go, I start going more chronologically, but I will still often just be like, I feel like writing this now. Or I just had an idea about this scene and I need to put that in.

AD: The books are also a romance between two people who think very differently, and it’s been interesting to see how that has developed.

MO: This was another example of me going, what do I like? I don’t know why, because I get very frustrated with the originals, but Holmes reboots or retellings are just catnip to me. Why? I think it’s that teamwork and relationship. Which is sometimes platonic and sometimes romantic, but it’s always a relationship between two people who think very differently. Holmes in the originals is very much about his mind being strange, and how he finds a usefulness for this. It becomes a talent, but you can see many situations in which it’s an obstacle. Watson is his collaborator in many ways in terms of figuring out how to relate to him. One thing that I really don’t like about the originals is how often Holmes is not very respectful of Watson and his brain functioning. In a lot of the reboots, that changes. In a lot of the retellings, people are saying, okay, we’re gonna have a character who sees his value. In the original, Holmes values Watson to a certain extent, but thinking about how they work together with these very different brain functionings, and the way that illuminates the two characters. I think that’s really interesting. It’s fun. I think it’s very relatable. Certainly for me. Maybe for other people, too.

AD: I think that’s some of the coziness, the comfort of it, as well. It’s not just a puzzle, but it’s solving a puzzle with someone.

MO: Absolutely. It’s the people and the relationship. I find I’ll read a mystery the first time to find out what happens, but I’m going to reread it because I want to spend time with the characters.

AD: Science fiction mysteries have a mixed reputation, I think, because we’ve all encountered bad ones–

MO: And, bad mysteries, I think we’ve encountered a lot of bad mysteries.

AD: Yes. Sturgeon’s law applies, as with all things. But we’ve all encountered science fiction mysteries where it seems impossible and the solution is some device. Which isn’t satisfying as a mystery or drama. When a science fiction mystery is well done, it’s because it’s about the individuals, it’s about the world, it’s a much more organic story than simply some device.

MO: I think that’s very true for science fiction in general. I mean, it’s great to think up a cool device, but that’s not a story. For me at least, the interesting thing is not the device, but what does that do to society or people? How do they change because of it? How do they rearrange? How do they reappropriate the device itself? So it’s fine to set a murder mystery on Jupiter, but for me, the interesting part of the series is, how did they get there? What are they doing to get to get away or stay or both? And for a mystery, what’s great about it is, what are the constraints of this place? Like, it’s very easy for things to disappear. They have real limitations on communication. What are their values? What’s important to them? What’s taboo? This is what makes it really fun to think through and explore. Because like I said, I don’t know the answers when I start. [laughs]

AD: There’s a way in which Victorian or Regency society feels like a very different world for us– just as an undated future where we’re living on Jupiter does. We’re conscious that it’s a constructed world with a constructed set of rules, which we’re trying to understand, and are partly illuminated through the act of solving this crime.

MO: I always like the books that don’t tell you everything. Part of that, I think, comes from reading things like Tolkien, where you always have this sense that there’s just this enormous amount of lore. When I was a kid reading Lord of the Rings, I didn’t know that it was all written down. It was just like, wow, he just makes me think it’s all there.

Also, I spent a lot of my young adulthood living in different countries from the one I grew up in. The experience of arriving in a place, not understanding, and slowly starting to understand is such a wonderful one. I think that’s part of what I’m going for in my books. That balance of, you don’t want the person to be completely lost, but you want them to be discovering. You want them to be doing some of the brain work. To me, that’s also where the fun comes in. Going, now I understand why they said that. Now that makes sense to me.

AD: I keep thinking of the books as very political.

MO: Yes! Which is interesting because a lot of people say, it’s such a departure from Infomocracy.

AD: They’re not overtly political, but they’re all about our relationship to the past. As someone who went to graduate school for history, there was a scene in the first book where I went, oh, you’re coming after the historians here, and they totally deserve it. [laughs]

MO: [laughs]I love hearing that. I don’t know if I’m coming after the historians so much as coming after the fetishization of history in our culture. That’s very politicized right now. I think it’s politicized often.

AD: Maybe always.

MO: Maybe always. I’m not coming after it only in the narrowly defined “political” sense. One of the things that has been really fun and fascinating for me in writing these books to look at our own time through that both glorified and sort of blaming lens of history. To imagine this huge schism that has happened and how that affects this looking back on history. It’s continuing to be a really powerful theme through the books. This question of where we put value. At the time, I didn’t mean to write a book about the pandemic. [laughs] I was really trying to escape from the pandemic! But it ended up having a really strong connection to that in the sense of chasing this idea of normal at the expense of all else. And at the expense of thinking about how to make things better, as opposed to just going for the familiar. And a resistance to recognize change.

AD: The first book was a novella and I thought it could have stood on its own.

MO: It’s remarkably standalone. I could have just said, okay, but I had so much fun with this. I did not want to stop.

AD: I can tell. And in each book you’re really trying to write a different book. And since that first one, write a longer book.

MO: One of the things that I’ve been really trying to challenge myself with is keeping it as a romance after the first book. A lot of romances, they get together, and then maybe the second book is a different pair. Or there’s an on again off again thing. It’s very tricky in the narrative conventions of our society to have a romance that goes beyond that first, oh, yes, I like you too. Thinking about how this relationship unfolds, and what the challenges are, and really trying to look at what it feels like. Even in Regency time, once they got married, they had a whole lot of back and forths. It’s not like, oh, we love each other, and we’re done. It’s, now we’re in a relationship. Are we staying in the relationship? Are we not? How much of relationship is it? How intimate are we emotionally? Are we committed? Are we still trying it out? To look at those different– I don’t know if stages is even the right word, because it’s, it’s so idiosyncratic, it’s different for each relationship– but looking at the different configurations that can happen.

This is maybe something of a departure from the classic detective series, but for me, it’s important to make sure I’m pushing myself somehow in each one. So it’s not a repetition. Like I said, with the romance, I think there’s a very clear challenge there. With the mysteries, what I’m aiming for and I don’t know if I’ve managed this so far, but to have a somewhat different shape of mystery each time. Whether it’s the way they get drawn in, or the pacing, or what happens. For me, it’s a very rich place to be working.