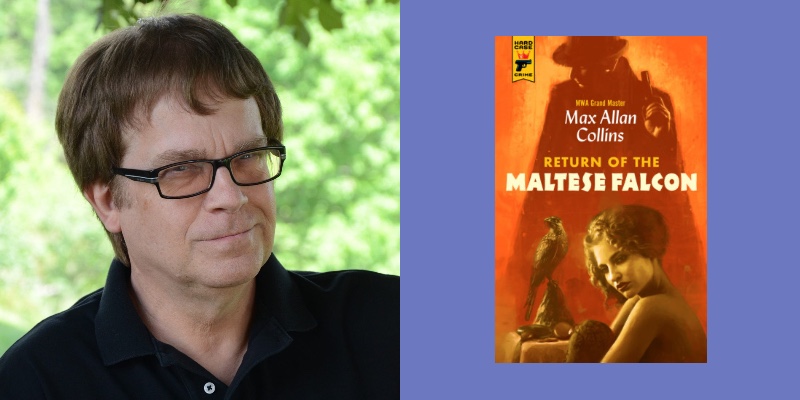

Max Allan Collins has been named a Grand Master by the Mystery Writers of America and received the lifetime achievement award from the Private Eye Writers of America for his decades-long career. The number of books, movies, comics, audio dramas and other projects he’s made over just the past few years show he’s not interested in slowing down. This year, the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of his first novel, begins with the publication of Collins’ newest book, Return of the Maltese Falcon.

A sequel to the Dashiell Hammett classic, Collins’ novel takes place shortly after the original story’s end and picks up some of the threads and unanswered questions, in particular: where is the real Maltese falcon? I spoke with Collins recently about how rereading Hammett was the initial inspiration for his long-running Nathan Heller series, the unique brilliance of The Maltese Falcon, the 1931 film version, and how the key to writing a sequel was not damaging the original.

You’ve written about how rereading The Maltese Falcon was the impetus for your Nate Heller series. I wonder if you could tell that story.

I was teaching at Muscatine Community College. This was the first job I had – the only job I had – after graduating from the University of Iowa Writers Workshop. I was really bored out of my mind teaching. I kind of had a knack for it, but I felt like the same energy went into teaching that went into writing, and I was trying to be a writer. One of the classes I taught was mystery fiction. Not how to write it, just how to read it.

The first book that I offered was The Maltese Falcon. I was preparing by reading it as a teacher, as opposed to as an author or just as a reader. I happened to notice that it was copyrighted 1929, 1930. The ’29 copyright was for the serialized version that appeared in Black Mask, and the 1930 copyright was for the publication by Knopf. Just a fleeting thought, oh, 1929, that’s the St. Valentine’s Day massacre. That means Sam Spade and Al Capone were contemporaries. Then I had a light bulb moment of, wait a minute, that means the private eye has now been around long enough to exist in history.

I think Chinatown may have been released by then. I know that Stu Kaminsky had written some of his Hollywood mysteries. There had been some TV shows. That the private eye could exist in period was out there, but I hadn’t made that direct connection. Chinatown draws upon history, but it moves history up and all the names are changed. But I could literally take a private eye and put him into a famous crime, a famous situation, and that was an eye-opener for me. I had grown up wanting to write private eye novels. I loved Hammett, I loved Chandler, and everyone who knows me knows I love Mickey Spillane. I really started trying to be a writer in the late ‘50s, early ‘60s, when I was still in junior high. There was that influx of private eye TV shows. A lot of the private eye shows, were based on or inspired by Hammett, Chandler, and Spillane. There was a Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer TV show with Darren McGavin, which is where I first encountered the character. 77 Sunset Strip came from Roy Huggins’ early novel, The Double Take. There was a Philip Marlowe show. There was a Thin Man show.

I always was somebody that if I liked a movie or a TV show, and there was a literary source, I’d go out and read it. The private eye had become out of fashion as I got to the age where I might be good enough to publish something. I got caught up by the Richard Stark Parker novels and James M. Cain and Jim Thompson. I veered into, I’m going to write books about crime from the point of view of the criminal. That’s where my series about Nolan, the professional thief, and my series about the professional killer, Quarry, came to be. That was what I had been doing at the University of Iowa. My first three novels were written at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

Those were the first Quarry and the first Nolan books, and the first Mallory novel, who wasn’t a PI but was an amateur sleuth.

They were amateur sleuth novels permeated by the hardboiled approach. They weren’t private eye novels, but really they were private eye novels. I should say that Robert B. Parker had not yet written his novels about Spenser. My friend Sara Peretsky had not started writing about V.I. Warshawski yet. That new wave of private eye writers had not started. I was still looking for a door I could go through to write private eye novels. That 1929 door was the one that did it. You may know this, I conceived Heller as a comic strip. It was actually sold to the Field Enterprises. It was sold to an editor there who loved it. And then he got fired. His name was Rick Marschall. He and I were working on developing a comic strip about a private eye. And my first continuity was about Harry Houdini. Not Harry Houdini himself, but the seances trying to bring Harry Houdini back. Which was a real thing. Houdini’s wife was involved in that.

A couple years later, I had already written the first few novels in my various series and I got approached to do the Dick Tracy comic strip. One of the people who had recommended me was Rick Marschall, who had bought the Heller comic strip. That was my first big career break. I did the strip for fifteen years. It got me noticed by a lot of people. It’s pretty common now, but it was not common then for somebody who was a “real” mystery writer to be writing a comic strip or comic books, and I was doing both.

You were ahead of the curve in that.

I was a bit ahead of the curve. The other thing was, I felt like my Nolan and my Quarry books were relegating me to a paperback originals writer. I had serious ambitions. No one had written a 100,000-word first-person private eye novel. Don Westlake encouraged me not to do it. He said that’s not going to be sale-able. But Mickey Spillane thought it was a good idea. [laughs] That opened the door to my doing a private eye series, which was my dream. We’re now at something like nineteen novels, not counting three novellas and a bunch of short stories. To me, that’s my signature work. I love Quarry. Quarry is a lot of fun to write, because I don’t have to do too much research. The thing about Heller, and this impacted the Maltese Falcon project, is how much research is involved.

Now how long have you been thinking about a sequel to The Maltese Falcon?

I was interested before public domain was even a glimmer in the popular culture’s eye. Probably ten years I kept my eye on that. Had I been thinking specifically about what book I was going to do? No. I just knew, Sam Spade’s going to come into the public domain. I thought, let me see if anybody’s interested in this. I had a very short proposal. The idea was basically pick the story up a week or two after the first one ends, because they never did find the Maltese Falcon. Now, I understand that that’s part of what was in the fabric of what Hammett was up to with his art. That was the overriding irony, the search for something we never find. I also know people were always thinking, it would have been nice to find out what happened to the Maltese Falcon. That opened up a certain amount of, not Heller-level research, but there was a lot of research. I did not have a working knowledge of what San Francisco was like in 1928.

Don Herron, who does a walking tour of Hammett and Sam Spade’s world, has a wonderful book about San Francisco. Also he has the best Spade-centric biography of Hammett. There’s a book out that illustrates The Maltese Falcon with lots of period photos. I have always used the Federal Writers Project books on the Heller books. I have one on San Francisco and one on California. They were published in the early 30s so they really pertain to this period.

The other decision I made, there’s a lot of stuff in The Maltese Falcon that happens offstage, characters who are mentioned never appear, who are significant in the story. I thought, there’s enough characters here who survived the end of the novel, and who never appeared onstage in the original novel, that I can draw upon Hammett’s world, and Sam Spade’s world without infringing upon it. Without damaging it in any way. That was important to me.

Besides not damaging the original, what had to be in the book? What did you want to avoid doing in the book? Because it is, for you and a lot of people, a beloved book.

It is a beloved book, but I was not particularly intimidated. Not that I think I’m on a level with Hammett. I certainly am not. I did complete fourteen books that Mickey Spillane started, and he’s a pretty heavy hitter, at least in my estimation. I took over Dick Tracy for Chester Gould. These are giants.

You’ve stepped into big shoes before.

I have stepped into big shoes before. But these were particularly, uniquely big shoes. I mean, we’re talking about the guy who invented the modern private eye story. Invented it, perfected it, and abandoned it. That’s pretty heady stuff. I was cognizant of that. One of the main things I did was curtail my own general approach. I would say I have more in common with Chandler and Spillane than I do with Hammett. What I tried to do was not completely take my style and my approach out of it, but curtail it. I didn’t want to imitate him. I didn’t want it to be a pastiche. The key to that for me was his supposedly objective style

Which is not objective at all.

It’s really a limited third-person omniscient style. Hammett only tells you what Hammett feels like telling you, and what he thinks you need. Spade doesn’t give you a fucking thing. The central mystery of The Maltese Falcon is not the Maltese Falcon, it’s Sam Spade. He doesn’t completely reveal himself until the final confrontation with Brigid O’Shaughnessy. And arguably doesn’t reveal everything even then. Based upon what I’ve read about Hammett, Spade is the most Hammett-like character. I certainly don’t think Hammett is Nick Charles. I certainly don’t think he’s the Continental Op. He might be Ned Beaumont. Spade in a way his idealized self and his admission of his quirks and limitations as a human being. I hesitate to say he’s a moral man, but Spade is navigating an amoral landscape where if you’re going to play by the rules, you have to invent them.

I don’t say that I pulled this off, but it was similar to what I tried to do with Mike Hammer. I never overtly tried to imitate Mickey’s voice. What I tried to do was understand who Mike Hammer was. I wanted to get the character right. I was trying to complete the works that Mickey had begun at different parts of his life, so before I started writing I would read two or three things of his that were written around the same time as the partial manuscript, to try to understand where the writer is and where the character is at a given point in time. Hammett is easy because he only did the one Spade novel. The three short stories, which are good little short stories, are pretty indifferent compared to The Maltese Falcon. He seemed to realize that all that is left after The Maltese Falcon is for Spade to be another recurring character. He was fine with somebody else doing that. He might have written more if, first of all, he drank less. We know that. Also, there was a Sam Spade radio show, a Thin Man radio show. You have Thin Man movies, and of course, he wrote the stories for the first three.

There’s a lot of Sam Spade stories even if Hammett only wrote one book.

The single trickiest thing is that there’s so little onstage action in The Maltese Falcon. Almost none. Most of it happens offstage. He gets rough with Wilmer once. He slaps Cairo. I had to put some action in it without doing more than he did in other novels of his. Because there is action in his short stories. There’s action in the Continental Op stories. There’s more than a little action in Red Harvest.

Like you say, so much of the book takes place off stage. The lengthy explanation of the falcon’s origins is the least of it.

Spoiler alert. Casper Gutman, the villain, is killed off stage. By the way, readers – there was this gun fight when you weren’t around.

It’s like one paragraph. He’s dead and the guy who shot him got away. Moving on.

What genius it is for a writer to be able to do that, and for people to remember The Maltese Falcon as an exciting book! The Huston movie seems to be very exciting, and there’s actually less action in that in that movie than in the book. One of the things that that Don Westlake turned me on to was the 1931 movie.

I haven’t seen it.

Obviously it’s not as faithful, or as brilliant as the Huston movie is, but it’s worthwhile to watch. I think one of the Bogart DVD collections includes it as a bonus feature. It has scenes that were left out of the Huston film. Specifically the Bridget O’Shaughnessy striptease scene.

Because they could get away with that in ’31.

Exactly, and be more overt. It was Pre-Code. There’s a moment where Spade either seduces or is seduced by Bridget O’Shaughnessy, spends the night with her, and while she’s asleep he goes out and checks up on her. That is not in the Huston film. I did not revisit the Huston movie. I’ve seen it a dozen times. I did revisit it, for fun, after I wrote the book. Bogart is not Spade. Bogart is a version of Sam Spade, but Bogart is no more Sam Spade that he was Philip Marlowe, and he wasn’t really either one of them. Dick Powell was Philip Marlowe in Murder, My Sweet, as far as I’m concerned.

A main thing for me was: no Bogart stuff. I think of Spade the way Hammett described him. I started pretty much with the initial description. There’s a lot of smoking. There’s a lot of drinking. There’s a lot of calling women “girls.” All that stuff that you’re not supposed to do now. Because that was the way Spade viewed the world. I loved doing it. It was as much fun as writing a Quarry novel. When I’m writing Heller, I have to stop to read for two hours to write a paragraph. It’s a slog getting through Heller and a challenge to make it read like this is the easiest thing in the world. I want a reader to take it down like a really great meal. It’s so good, you know you should eat it slowly, but you rush through it anyway because it’s so delicious. That’s what I’m after.

One of the big differences is that you utilize a lot more description.

I have to. Hammett wasn’t writing a period novel.

That level of detail is rarely included in a contemporary novel, but those details are one of the pleasures of reading historical fiction.

It wouldn’t have occurred to Hammett to describe anything in that kind of detail. I have been accused of over-describing things. That is an aspect of my fiction that I’m aware of, and I know some people don’t like. I get heat sometimes for describing clothing. I always say, well, I don’t want a bunch of naked people running around in my books, unless it’s a sex scene. I have to see it. I am, in my modest way, a filmmaker. I have to see it before I write it.

You do describe clothing in detail, but Hammett was very precise about clothing. The collars, the shirts, this kind of jacket, that kind of dress, and very precise about how clothes hang, how people wear them.

He’s very specific about that. I love that that he was at least as specific about the clothing as I was. But in general, I have to take the reader on a time machine, and Hammett didn’t.

What was your biggest fear about writing this book? Besides bringing a comparison to Hammett.

It really was exactly that. I was very proud of this book when I finished it. My wife Barb said to me, “You know, you’re going to get beat up. There’ll be people who like this, but…” I said, yeah, it is a kind of suicide note. I’ve never allowed myself to think that way until after a project. When the word came out about this book, I was attacked. How could he? I sat back and said, I’m not going to listen to anybody who hasn’t read the book. If you read the book, and you didn’t like it, fine. I don’t feel I’m taking anything away from The Maltese Falcon. It is in the public domain and somebody would have done this. I wanted it to be done correctly. Which of course is whatever I think it should be. [laughs]

I’m sure there’ll be some bad reviews. We’ve been very lucky so far. Publishers Weekly gave it a starred review. Kirkus, who have routinely hated me at times, gave it a near rave. Booklist was a flat out rave. They understood that this was coming from a good place. It comes from my love of his work. My love of the genre.

You love the original and you love the genre.

It’s amazing to me that Hammett wrote this book and invented it all. It’s all in there. The private eye. The secretary is in love with him. The cop friend. The cop adversary. The weasly hood who’s attached to the big villain. The femme fatale. Spade cheating on his partner with his partner’s wife did not become a trope, however.

The door that was left open at the end of the Hammett narrative isn’t as much of what became of the Maltese Falcon, but how is Spade going to extricate himself from the ruins he’s made of his life and business? That was part of what I could write about. The Hammett novel does not end as the movie did with the line about “the stuff that dreams are made of.” The book ends with Effie, who loves Spade, and I think he loves her, as capable as he is of love, which is probably fairly limited. She says, Iva’s here, and he says, send her in. At the end, he doesn’t have the Maltese Falcon. He doesn’t get the girl. He didn’t really make any money. He even turns over the bribe money to the cops so that he doesn’t get caught up in this. These was the big unresolved things that really made a sequel, particularly an immediate sequel, attractive to me as a writer. There’s a moment in the book where he does very momentarily, and it’s emphasized in the Huston movie, become caught up in it. When he and Effie take the wrapping off of this figure that’s worth so much money, that so many men have died for. Then he pretty much calms down. It’s just a little human moment in there.

I love that I got to do this. I’m very pleased that there are people who are receptive to it. I understand if you aren’t. I understand if you’ll never read that book. But I’m not the first person to do a post-Hammett Spade novel. Joe Gores wrote one. There was the Howard Duff radio show. There was a comic strip for Wild Root Cream Oil. Which presumably Hammett took money from. [laughs] If Hammett was willing to take Sam Spade money from a hair tonic manufacturer, why should I be too worried about my ethics here?

He didn’t hold this in the kind of reverence that some of us did. He was perfectly happy to be like, yes, go make a radio show, a tv show.

I’ve been asked, do you think Hammett would be pleased by how he’s viewed today? During his lifetime, I don’t think he felt any huge pride in what he’d done. He had enough that he did allow all his early stories to be gathered into books. He didn’t have contempt for his novels, but he had no interest in continuing in that vein, because he had serious ambitions as an author.

Still, I think he would be very pleased. Any author would be to see that it has been accepted in the way that his work has been. He had a little inkling of that when the Modern Library published The Maltese Falcon, and wrote that wonderful introduction. He talked about which stories he had done for Black Mask that he drew upon. Not to the degree Chandler did, where Chandler essentially cut and pasted his stories and then rewrote them, but he was drawing upon that ephemeral pulp material. I not only think it’s the greatest mystery novel ever written, I think it’s better than The Great Gatsby, quite frankly. I like The Great Gatsby, but I’m not convinced that Hammett won’t outlive Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. You’ll never convince me of that.

The book does have one scene with Brigid where he visits her in jail. It’s a scene where I initially thought you softened her a little, but by the end it really worked on many levels and came together beautifully.

Thank you very much. That was an early question. I really did have to think quite a bit about that. I knew what the Cairo scene would be. But what does Spade feel about Brigid now? You certainly do not want to sentimentalize. I’ve been accused of being sentimental in some of my books. I’m a believer in sentiment. I’m not a believer in sentimentality. I think there is a difference. You have to feel something.

I think it’s easy with historical work, with sequels, you have some sentiment because that’s what you’re bringing to it. That’s why you’re writing it.

I think so.

I went into this aware that there were a lot of people who would like to have another Sam Spade novel by Dashiell Hammett. They weren’t waiting for Max Allan Collins to do it, but Hammett isn’t available.

To close, we talked a little about Mickey Spillane, and you completed his unfinished work. Now you’ve written a sequel to Hammett. You’ve completed a number of projects in the past decade. You co-wrote two nonfiction books about Elliot Ness and a biography of Spillane, the reprints of the complete Ms. Tree, the comic series you made with Terry Beatty. You also wrote and directed a few movies. Have you been thinking about your own work and leaving it in a way that satisfies you?

That is a major concern. I was pretty close to Chester Gould, the creator of Dick Tracy. When I got the strip originally, we visited him at his home, my wife and I. We were sitting in his kitchen and having some little thing that his wife Edna had made for us, a dessert or something. He said to me, in his Chester Gould way, “Make sure this isn’t the only thing you do, because it isn’t your own.” He didn’t mean that in a mean way at all. He thought I had talent and he thought I shouldn’t spend my life just writing someone else’s creation.

I got fired off the strip, after fifteen years, when an editor came in and didn’t like me. Or my work, but particularly didn’t like me. [laughs] That was when I got the chance to do Road to Perdition. I always think about Dean Martin saying the two best things that ever happened to him were teaming up with Jerry Lewis and breaking up with Jerry Lewis. A door closes and you find a window to crawl in. That’s what I did. While I have this fan-ish aspect about Mickey, about Hammett, about Chandler, even about Dick Tracy, I don’t think anybody can accuse me of not creating my own body of work. And frankly, my body of work would be taken more seriously if I hadn’t done this other stuff. I wrote novelizations for fifteen years. My agent at the time said, you shouldn’t put your name on these. I said, if I don’t put my name on them, I won’t take them seriously as I’m writing them. I’ve always felt you have to own what you do, and bring your best game. I honestly don’t think I’ve ever phoned anything in, and I’ve never allowed anything, even the Mickey stuff, to be the primary thing I do.

You have a body of work, an oeuvre which is uniquely yours, but a lot of people get looked down on for being prolific. Often because they have to be prolific.

We venerate Hammett and Chandler, and we should, but Hammett has five novels. What is Chandler, eight? I’m trying to make a living here.

I’ve mentioned Don Westlake a lot because he’s been on my mind lately. He loved W.R. Burnett. As I do. He said, the difference between W.R. Burnett and Chandler and Hammett is that he wrote too goddamn much. He was trying to make a living. He was a real pro. I’m not saying that Hammett wasn’t, because he had a long history of working in the pulps. Chandler had a history in the pulps. I’m not putting Erle Stanley Gardner on a level with these guys, but he’s pretty good. Rex Stout I would put pretty damn close to the upper tier. He doesn’t get the credit that he deserves because he wrote 70 Nero Wolfe stories.

Writers can’t do anything about how the world perceives them. I want the editors to like the stuff enough to publish it and send me a check. I want the reviewers to like it well enough to not get in my way. I never take a review seriously. Well, no, I take the bad ones seriously. I’m very, very thin-skinned. It’s been very difficult for me, on occasion, not to respond to bad reviews. It’s a lot easier to write a page about a book negatively than to write a whole book.

You said before, when you write the book, you’re focused on the book. How it’s perceived, and everything else, you can deal with after. Writing the book is its own thing and needs to be its own thing.

What helps me in my life, I have been married to this beautiful woman– and she’s still beautiful– for 57 years. She feels her job in life is making sure I’m knocked down a peg when necessary. She keeps me grounded. The best thing about my writing life is being married to a writer. Having an in-house editor who has those kind of chops is extremely good. I really value having somebody who can keep me grounded. I think it’s been good that I’ve stayed in Muscatine, Iowa and not gone to Hollywood and had the things happen to me that happened to James M. Cain, for example. I don’t think Hammett was happy there. I know Chandler wasn’t. Chandler thought Billy Wilder was a hack. [laughs] The people who write popular fiction, I think, are very single-minded. The thing about writing a novel is, it’s your way. I like to collaborate, but I love the purity of my own work. That’s the pride I can take. I’ve written so many books, I can’t even remember some of them. But at the time, there was nothing bigger in my life when I wrote it.