New York, July 22, 1884

They were detectives, accustomed to plunder, But they’d never seen anything like this.

It had taken some doing to open the safe. After bursting into the modest haberdashery shop on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, they’d demanded the keys from the shopkeeper, Fredericka Mandelbaum. But Mrs. Mandelbaum, a towering woman of fifty-nine, tastefully attired in diamond cluster earrings and a lace-trimmed gown of dotted blue, held firm. “No,” she declared, in her heavy Germanic English. “Just to think of such a thing!”

Her refusal forced the detectives, employees of the storied Pinkerton Agency, to become safecrackers themselves. They summoned a blacksmith, who arrived at the shop with hammer and chisel. He attacked the safe; amid the din, a pretty teenage girl ran in from the next room—Mrs. Mandelbaum’s daughter Annie.

“Stop!” Annie cried. She handed over the keys and the safe was unlocked. An Aladdin’s Cave spilled out.

There were gems and jewelry of every description: rings, chains, scarf pins, bracelets, glittering cufflinks and collar buttons—“almost every ornament you could mention,” one detective recalled. Beside them were “heaps of gold watches” and, wrapped carefully in tissue paper, watch movements and cases. There was a clutch of fine silverware. There were loose diamonds the size of peas.

Elsewhere in the shop’s clandestine back rooms—protected by a metal grille and linked to the outdoors by a set of secret passages— the detectives came upon priceless antique furniture, a trunk brimming with shawls of the finest cashmere and curtains of exquisite lace, and bolts of silk worth thousands of dollars alone. Concealed under newspapers were bars of gold, fashioned from melted-down jewelry. Upstairs, in Mrs. Mandelbaum’s gracious bedroom, they found melting pots and scales for weighing gold and diamonds. She and an employee were promptly arrested.

With that, the Pinkerton detectives, who had staged the raid at the behest of the city’s district attorney, accomplished in a single outing what New York’s police force (1) had not managed to do in more than twenty years. “You are caught this time, and the best thing that you can do is to make a clean breast of it,” one of the Pinkertons, Gustave Frank, advised Mrs. Mandelbaum as she was led away.

In reply, Fredericka Mandelbaum—upright widow, philanthropic synagogue-goer, doting mother of four and boss of the country’s most notorious crime syndicate—whirled and punched him in the face.

*

For twenty-Five years, Fredericka Mandelbaum reigned as one of the most infamous underworld figures in America. Working from her humble Manhattan storefront, she presided over a multi-million-dollar criminal operation that centered on stolen luxury goods and later diversified into bank robbery. Conceived in the mid-1800s—long before the accepted starting date for organized crime in the United States—her empire extended across the country and beyond. In 1884, the New-York Times called her “the nucleus and centre of the whole organization of crime in New-York.” (2)

Revered in some quarters, reviled in others, Marm Mandelbaum, as she was known, towered over the city as an earthy, expansive, diamond-encrusted presence: self-made entrepreneur, generous philanthropist, thieves’ mentor and gracious society hostess who plied her illicit trade largely in the open. A swath of the public admired her. Many criminals adored her. Over the course of her long, lucrative career, she would spend scarcely a day behind bars. “Without question,” a twentieth-century criminologist has written, “the fullest attribution of energy, presence, and personal magnetism in the literature of criminology belongs to ‘Ma’ Mandelbaum.”

For Mrs. Mandelbaum, trafficking in other people’s property was staggeringly good business: Her network of thieves and resale agents was reported to extend throughout the United States, into Mexico and, it was said, as far away as Europe. At her death, in 1894, she had amassed a personal fortune of at least half a million dollars (in some accounts as much as a million), the equivalent of more than $14 million to $28 million today. (3) As the New York police chief George Washington Walling, (4) who knew her well, recalled, “The ramifications of her business net were so widespread, her ingenuity as an assistant to criminals so nearly approached genius, that if a silk robbery occurred in St. Louis, and the criminals were known as ‘belonging to “Marm Baum,”’ she always had the first choice of the ‘swag.’” In her heyday and for some years afterward, Marm was a storied figure, the subject of news articles, editorial cartoons and more than one stage play. (5) The world press covered her criminal prowess with a kind of grudging admiration; it covered her downfall with post-hoc smugness. (6) But despite her renown in her own time, she is far less well known today, an all-too-common fate for history’s women. Though there are passing references to Mrs. Mandelbaum in a spate of books on New York City history, there are few in-depth studies of her life and work.

Marm kept no written records: No fool, she clearly knew it would have been professional suicide to do so. As Chief Walling observed: “She was shrewd, careful, methodical in character and to the point in speech. . . . Wary in the extreme.” But her career turns out to have been amply chronicled, not only in the news accounts of her day, but also in the reminiscences of her contemporaries on both sides of the law. As a result, she can be conjured whole from the glittering nineteenth-century city in which she operated—the redoubtable star of an urban picaresque awash in pickpockets and sneak thieves, bank burglars and high-toned shysters. And from her glittering presence it is possible in turn to conjure the city: a wide-open town careering its way through “the Flash Age,” a time when the mantra of one suspiciously well-heeled pol, “I seen my opportunities and I took ’em,” was a guiding principle for many New Yorkers.

**

When twenty-First-century Americans hear the phrase “organized crime,” it almost always evokes the Prohibition-era, “guns-and- garlic” gangsterism of Scarface and The Untouchables. (7) But the term was first attested in the United States in the 1890s, and, as Mrs. Mandelbaum’s career makes plain, the practice was a going concern here well before that—in Europe, earlier still. (8)

Unlike the organized crime of the tommy-gun age, Fredericka Mandelbaum’s profession entailed little violence. She was, from the first, a specialist in property crime, buying, camouflaging and reselling a welter of stolen luxury items. Beginning her ascent in the late 1850s, she quickly established her reputation as a criminal receiver—a “fence,” in popular parlance. There had been legions of fences before Marm Mandelbaum, and there have been legions after. But what she accomplished had by all accounts not been done before in America on so broad a scale, in so sustained and methodical a fashion: Fredericka Mandelbaum transformed herself, almost singlehandedly, into “a mogul of illegitimate capitalism,” running her operation as a well-oiled, for-profit corporate machine. Strikingly, she did so more than half a century before the Prohibition-era syndicates celebrated in popular culture, a milieu in which women, if they featured at all, were little more than gangsters’ molls.

“Crime cannot be carried on by individuals,” a longtime member of the Mandelbaum syndicate wrote in 1913. “It requires an elaborate permanent organization. While the individual operators, from pickpockets to bank burglars, come and go, working from coast to coast, they must be affiliated with some permanent substantial person. Such a permanent head was ‘Mother’ Mandelbaum.”

Late-nineteenth-century newspapers reveled in Marm’s doings, and liked to say she could “unload” anything, including, in one account, a flock of stolen sheep. But it is beyond doubt that by the mid-1880s as much as $10 million (9) had passed through her little haberdashery shop on the Lower East Side. The full story of her rise to underworld stardom as “the undisputed financier, guide, counsellor, and friend of crime in New York”—and her ultimate fall at the hands of the city’s increasingly powerful bourgeois elite—is a window onto a little-explored side of Gilded Age America: the world of Herbert Asbury’s Gangs of New York from the perspective of a sharp-witted, fiercely determined woman. (10)

Some modern observers have called Mrs. Mandelbaum a proto-feminist. Perhaps she was, though she appeared as committed to wifely and maternal duties as any woman of her era. What can be said with certainty is that she was among the first—quite possibly the very first—to systematize the formerly scattershot enterprise of property crime, working out logistics, organizing chains of supply and demand, and constructing the entire venture first and foremost as a business. And in so doing, she simultaneously embodied and upended the cherished rags-to-riches narrative of Victorian America, starring, on entirely her own terms, in a Horatio Alger story of a very different kind.

***

Arriving in New York in 1850 with little more than the clothes on her back, Fredericka Mandelbaum began her working life as a peddler on the streets of Lower Manhattan. Professional advancement, to say nothing of great wealth, seemed beyond contemplation for someone who, like her, was marginalized three times over: immi- grant, woman and Jew. (Organized crime, as a twentieth-century writer has sagely noted, “is not an equal-opportunity employer.”) Yet before the decade was out, she had established herself as one of the city’s premier receivers of stolen goods; by the end of the 1860s she had become, in the words of a modern-day headline, “New York’s First Female Crime Boss.”

Though she stole little to nothing herself, Mrs. Mandelbaum trained a cadre of acolytes to help themselves—and thereby help her —to the choicest spoils that Gilded Age America had to offer. She orchestrated decades’ worth of high-end thefts, selecting the foremost men and women for each job, underwriting their expenses and advising them on “best practices” peculiar to their trade: why it’s especially prudent for a thief to specialize in diamonds and silk; why, when entering an establishment like Tiffany & Company, it is supremely helpful to be chewing a piece of gum; how to dress for success—success, that is, in pilfering luxury goods from department stores; and, ultimately, how to relieve a bank of its contents.

“What plannings of great robberies took place there, in Madame Mandelbaum’s store!” one old-time crook recalled fondly. “She would buy any kind of stolen property, from an ostrich feather to hundreds and thousands of dollars’ worth of gems. The common shop-lifter and the great cracksman (11) alike did business at this famous place.”

Mrs. Mandelbaum bailed out her disciples whenever they were arrested, wined and dined them at her groaning table, supplied fistfuls of cash when they were down and out, and furnished getaway horses and carriages as the need arose. For her maternal devotion to her handpicked phalanx of foot soldiers—her “chicks,” she called them—criminals and the press alike referred to her as “Marm,” “Mother,” “Ma” or “Mother Baum.”

“There is still standing, I believe, a little . . . house at the corner of Clinton and Rivington Streets, which was for many years the headquarters of some of the greatest criminals in the country and in which many of the most daring robberies of the period were planned,” an American newspaperman wrote in 1921:

The front part of the ground floor was devoted to the sale of cheap dry-goods but the parlor in the rear contained many articles of furniture and silver of a sort seldom seen in that quarter of town. It was in this room that “Mother Mandelbaum,” as she was affectionately termed by more than one generation of crooks, transacted business. . . .

Her place of business [was] a market in which jewelry, rolls of silk, silverware and other spoils could be disposed of for about half their real value, the old lady assuming all the risks of the transaction. . . . She looked as if she might have stepped out of the pages of a Viennese comic paper, yet she was a sort of female Moriarty who could plan a robbery, furnish the necessary funds for carrying it out and even choose the man best fitted to accomplish it.

If that isn’t the textbook definition of an organized-crime boss, then I don’t know what is.

****

In any era, Mother Mandelbaum would have cut an imposing figure, but in her own time she fairly loomed over New York. About six feet tall and of Falstaffian girth (she was said to have weighed between 250 and 300 pounds), pouchy-faced, apple-cheeked and beetle-browed, she resembled the product of a congenial liaison between a dumpling and a mountain. She dressed soberly but expensively in vast gowns of black, brown or dark blue silk, topped by a sealskin cape, with a plumed fascinator or bonnet. She dripped diamonds—earrings, necklaces, brooches, bracelets, rings—but then, in her line of work, diamonds were as easy to come by as the ostrich feathers that waved gaily from her hats. “Her attire was at once gorgeous and vulgar,” the Cincinnati Enquirer observed in 1894. “She often wore $40,000 worth of jewels at once.” (12)

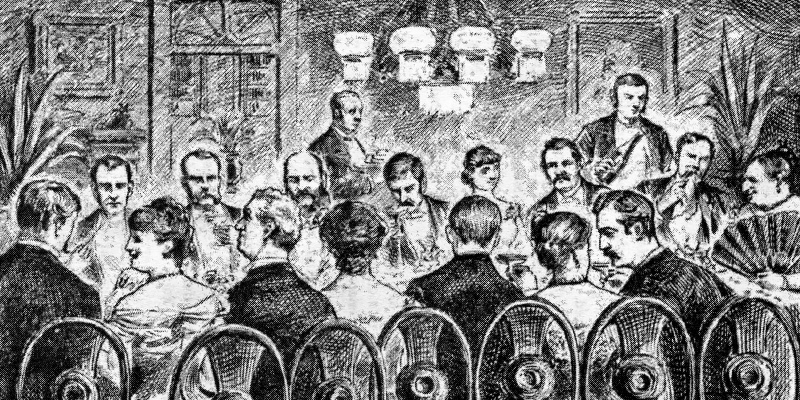

Mrs. Mandelbaum lived above the shop, but the ground floor of her clapboard building, with its unremarkable public salesroom, did little to hint at the New World Versailles above. A look in on one of her famous dinner parties—sought-after affairs as opulent as anything Mrs. Astor might give uptown—starts to convey the full effect:

Inside Mrs. Mandelbaum’s apartment, her guests, attended by her large staff of servants, are dining on lamb, accompanied by fine wines from her extensive cellars. Here, at the head of the mahogany dining table, Marm, swathed in silk and weighted down with diamonds, sits on a wide embroidered ottoman, making animated conversation. Down one side of the table, in full evening dress, are some of the most distinguished members of uptown society, leading lights of New York commerce and industry. Down the other, also in evening dress, are the crème de la crème of criminality: Adam Worth, a master thief who learned his craft at Mrs. Mandelbaum’s side; the bank-burgling virtuoso George Leonidas Leslie; pretty, light-fingered Sophie Lyons, a shoplifter who under Marm’s tutelage became “perhaps the most notorious confidence woman America has ever produced”; and Sophie’s husband, the bank burglar Ned Lyons, who was said to have fallen in love with Sophie at one of Marm’s parties, after she presented him with a gold watch and handsome stickpin she’d just lifted from another guest. In a corner, playing Beethoven on Marm’s white baby grand, is “Piano Charley” Bullard, a trained musician who regularly turned his nimble fingers to safecracking.

Marm’s table, adorned along its length with gold candelabra, is laid with the finest china and crystal, and set with silver that “would have been rated as ‘A+ swag’ had a ‘client’ of the old woman called on her to dispose of it,” a knowledgeable visitor recalled. The windows are hung with rich silk draperies; the furniture is of ornate Victorian mahogany that “would have attracted the cupidity of an antiquarian”; the floors are cushioned with thick carpets of red and gold; the walls are a profusion of rare old paintings; and the coffered ceiling is hung with crystal chandeliers. “Scattered about the room,” a newspaper recounted, are “many pieces of bronze and bric-a-brac, the retail price of which is beyond the reach of ordinary mortals.” If some of Marm’s furnishings look remarkably like items once owned by her blue-blood uptown guests . . . well, in an age of mass production, who can truly be certain? (13) In any case, as one guest recalled, the entire evening would have been “conducted with as much attention to the proprieties of society as though Mrs. Mandelbaum’s establishment was in Fifth Avenue instead of in a suspicious corner of the East Side.”

*****

The most remarkable thing about Marm’s calling was that she pursued it for decades with almost complete impunity: Until her downfall, in 1884, she hadn’t spent so much as a day in jail. “The police of New York were never able to catch Mother Mandelbaum,” the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that year. “Any citizen could go to her place and see her in the act of carrying on her trade, and yet 2,500 policemen, the expensive detective bureau and the vast machinery of the force was utterly unable to arrest her.”

There were two primary reasons she was able to skirt the law for so long. The first was that she kept on permanent retainer two of the most satisfyingly crooked lawyers American jurisprudence has ever known. The second, even more vital, can be gleaned from a renewed look round her table. Here, seated in Marm’s carved mahogany chairs, wining, dining and laughing alongside the tycoons, the swindlers and the shoplifters, are—

But, no. We are getting ahead of ourselves.

___________________________________

(1) The force, which bore various names over time, would not be known as the New York City Police Department until 1898, when the five boroughs that constitute present-day New York were consolidated into a single city.

(2) Until the late nineteenth century, “New-York” was often hyphenated, in the manner of compound adjectives. The New-York Times was among several of the city’s newspapers to employ this form; then, on December 1, 1896, “without a word of explanation to readers,” the Times jettisoned the hyphen forever.

(3) Here and throughout, contemporary dollar figures reflect the historical inflation rate of late 2023, when this book went into production.

(4) Walling (1823–91) served as superintendent of police, as the chief’s post was then known, from 1874 to 1885.

(5) The plays include The Two Orphans (Les Deux Orphelines), an 1874 French melodrama featuring the nefarious matriarch of an underworld family, produced in New York in English translation that year, and The Great Diamond Robbery, an American melodrama by Edward M. Alfriend and A. C. Wheeler, which premiered on Broadway in 1895, the year after Mrs. Mandelbaum’s death. That production starred the Prague- born actress Fanny Janauschek as “Mother Rosenbaum,” a successful receiver of stolen goods indisputably modeled on Marm.

(6) Mrs. Mandelbaum’s death, for instance, was reported in newspapers throughout the United States and as far away as London.

(7) In keeping with common usage, this book employs the phrases “organized crime” and “syndicated crime” interchangeably.

(8) These days, one analyst notes, “organized crime” is “a fuzzy and contested umbrella concept”: It has been applied variously—at times promiscuously—to entities as distinct as the Sicilian Mafia, the Yakuza of Japan and the drug cartels of Colombia and Mexico. In short, about the only thing on which scholars of the field can agree is that when it comes to a precise definition, there is no agreement. It seems fitting, somehow, that the term is slippery and elusive.

(9) Equivalent to nearly $300 million today.

(10) Mrs. Mandelbaum makes several cameo appearances in Asbury’s book.

(11) A housebreaker or bank burglar.

(12) About $1.3 million today.

(13) As a member of Marm’s organization would write, “Servants of wealthy New York families learned that ‘Mother’ Mandelbaum paid well for tips and plans of houses.”