Two ideas exist simultaneously. 1) A nation is not conquered until the hearts of its women are on the ground. (Cheyenne); and 2) There is, and has been, a target on Native women’s backs for the past 500 years. Both are true in Indian country. For women in the western world this target dates to the Dark Ages in Europe, starting in 1222, when women were burned at the stake for being witches. In Europe it was powerful women who were seen as a threat, and as time passed it would seem that all women became a threat to the patriarchy.

A conquered nation’s women will pass on the cultural and spiritual knowledge to future generations. An unconquered woman will pass on the knowledge even when all appearances say the woman is conquered.

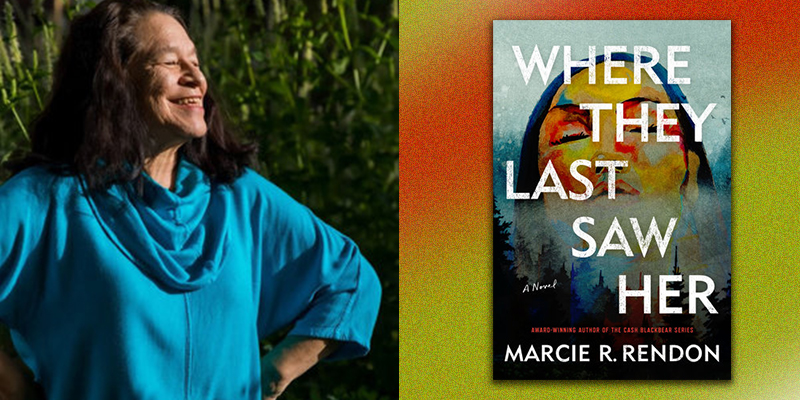

Historical trauma is a very real phenomena and that very real trauma dictates the decreased survivability of Native women. However, what is truth for me is that Native women are more resilient than our trauma dictates. It is the stories of those unconquered women whom I hope to portray in my writing of crime novels.

I write crime novels because I read crime novels. There is a joke, (Native people tell a lot of jokes) in Indian Country that asks, ‘What do Indian women watch for bedtime stories?’ The answer? ‘Law and Order SVU’ or any serial killer movie. And everyone laughs. Because it is true. Given the amount of violence Native people have survived for the past 500 years it is thought that by watching crime, reading crime, devouring stories of crime we attempt to keep the boogieman at bay, a way to survive vicariously through ‘others’ re-enactment of the terror.

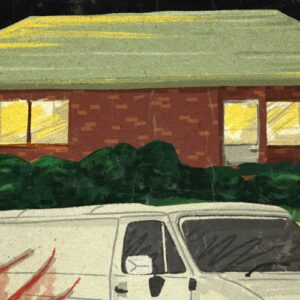

In Native communities you will also see families living life together. Need to go to the grocery store? Mom, grandma, a couple aunties and a few kids all pile into the car or pickup to go into town. Is there a pow-wow on the next reservation? Same thing, the whole crew piles into a vehicle and heads off.

Like many rural communities, Native people on reservations or living in border towns, grow up with the same people their whole lives. Those relationships endure for years. Yes, there are conflicts; but in a rural area, it is the people you have known your whole life who in good times and bad, they are the ones you count on. The friend you went to kindergarten with and graduated high school with. The woman from the community who stopped on the road and helped you change your flat tire because that is what community does. It is these women, women who have life-long relationships, women who have a history with each other, they are the ones who people my story in Where They Last Saw Her. They have each other’s back. Literally.

In my crime novels, it is the women who take on the perpetrators of violence against both women and men. In my everyday life, it is the women of my community who I see as brave and courageous. The ones, who even when living in fear themselves, will step forward to address very real situations. It is the women who see what needs to be done, and they do it. They act with integrity.

In 1985, there was a serial killer targeting Native American women in the city of Minneapolis. I remember Bonnie Clairmont, now an esteemed elder, but at that time a mother and community leader, who stepped forward and pushed the city and our community to protect our women who were moving about the city after dark, either returning home from work, shopping, or leaving a bar after a night out. She was scared like all of us were, but she stepped forward and did the courageous work needed to give voice to our fear and took action and encouraged others to take action where needed to protect women when possible.

It was the First Nations women in British Colombia who first stepped up and said, ‘Our women are being trafficked, murdered, and dumped along Highway 16. We need to do something.’ And they were the first to call attention to the violence directed at First Nations women by crews working in extractive industries. I remember reading a 2014 Canadian report on #mmiw, missing and murdered women, that said, ‘Our list of #mmiw is 90-typewritten-pages, single-spaced.’ 90 single-spaced pages of the names of missing and/or murdered First Nations women across Canada. Highway of Tears, a documentary film released in 2014, raised world-wide consciousness of the #mmiw issue across Canada.

As the extractive industry moved through the northern states of Montana, North Dakota and norther Minnesota, there became an increase in #mmiw in the United States. Ruth Buffalo, former North Dakota state representative, and Minnesota’s Senator, Mary Kunesh, both Native American women, used their elected status to get state legislation passed in their respective states to begin to address the alarming increase in #mmiw.

Lissa Yellow-Bird Chase, from White Shield, North Dakota, formed the non-profit Sahnish Scouts of North Dakota, to publicize and search, for missing persons. They work tirelessly for native and non-native families with missing family members. The Indigenous Protectors Movement was formed in Minneapolis, MN in the spring of 2022 to address the issue of our Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives. Again, the co-founder was a woman, Rachel Dionne-Thunder.

This list of Native women who rise to the challenge could go on and on.

It is also important to recognize the laughter and camaraderie women of a community have with each other. Like mentioned earlier, the joking and teasing is ever present. When oppression is hard, one way to keep going is to keep laughing. The other thing important to notice is the amount of care that women have for each other – they are tender and giving, which isn’t always apparent under the hard shell of survivance. I strive to shed on this side of Native womanhood-the care and compassion we exhibit towards and for each other.

Writing a novel about crime and women’s response to it, is an opportunity to acquaint ourselves and the non-native world with our brilliance, humor, resilience, strength, courage and integrity. I hope I do us well. Miigwech.

***