I can’t remember when I first noticed the ridges, but it was likely sometime between the ages of eight to twelve, at an age where I’d already experienced panicked adults talking about Big Things around the dining room table in hushed whispers.

As a child growing up in the 80s and 90s in Ireland, that meant staying indoors when easterly winds brought remnants of Chernobyl. It meant Tiananmen Square, the Fall of the Berlin Wall, the Exxon Valdez oil spill, the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Yugoslav wars, the end of Apartheid, the Rwandan genocide, and the Good Friday Agreement.

Yet in Ireland, we had enough to be worrying about, with a devalued currency, twenty percent unemployment, sixty percent income tax, escalating national debt, and rampant emigration.

We were a country crippled by economic crisis; a country paralyzed by political violence; a country overwhelmed by hopelessness.

But the Irish way of dealing with things is to always look outward. To dissect other people’s problems and the policies of other countries. Never look inward, never address your own issues. Keep your head down and get on with it. Suck it up. March onward.

You don’t need a psychologist, you just need some fresh air. Your leg’s not broken, put some weight on it. Sure, aren’t you grand? And what are you complaining for, aren’t you alive? Don’t you have a roof over your head? Isn’t there food on your plate? Twas far from new shoes you were reared. Stop acting the maggot. My grandmother would be rolling in her grave if she could see you now.

It seemed like the brave thing, the “made of iron” type of constitution that embodied what it means to be Irish…until I removed myself from that environment and entered the Irish diaspora. That’s when I discovered that it’s not normal, and there’s a psychological term for the way we are.

That term is collective dissociation: the use of dark humor and sharp irony to distance ourselves from pain, reliance on religious institutions to fill a power void in the wake of gaining independence, and making it a mortal sin to say the unsayable.

In the Ireland I grew up in, emotional or mental health struggles were taboo, ridiculed as “notions” or “nerves.”

In the Ireland I grew up in, political violence overseas was cheered and toasted, but political violence in Ireland was met with tight-lipped murmurs of “aren’t they a disgrace?”

In the Ireland I grew up in, the Irish language, Irish music, Irish traditions were rejected, and we were sent to elocution lessons to lose our Hiberno-English diction to “speak proper English.”

Collective dissociation is caused by trauma, specifically, generational trauma. Not from a single event, but from the systematic dismantling of a people until all that remains is gratitude that we’d made it. That we’re here because we stuck together, and that means keeping your head down, following along, and doing what’s expected of you. Of not rocking the boat, of doing everything possible to keep the status quo.

And there’s a word for that systematic dismantling: colonization.

“What are those ridges, Granda?”

Pursing his lips, my tall, stoic grandfather shaded his eyes and squinted into the distance. There on the hill, rippling in unnatural horizontal lines perpendicular to the field below, were strange ridges.

I must have walked past them a thousand times before without notice. But I was getting older, my world was expanding, and Granda — a man of very few words, but those few words were profound when spoken — always loved answering my questions.

Potato ridges.

I remember nodding, thinking it odd that someone would try to grow potatoes on the side of a hill.

What happened next changed my life.

My quiet grandfather squatted down, placed both hands on my shoulders, looked me dead in the eye, and said: They’re scars, Maria. Like when you cut your knee and it leaves a mark. The scars on your skin are the story of your life, and those scars, are the story of this country.

That’s all he ever said on the matter, but later, much, much later, I learned the truth.

In the field below that hill, there was probably once a one-roomed cottage, piled to the rafters with a family of ten or more. And in that field, cabbage, carrots, oats, or barley were grown—a fine turn-out that was sure to keep a family of that size fed.

But that food wasn’t meant for the family, it was for the landlord. Every last ounce harvested was piled onto a cart, year after year. From there, it was loaded onto ships and sent to England, where distributers sold to grocers. Those grocers then sold Irish-grown produce to the droves of English farmers that now occupied English cities—pulled off the land to become a cog in the great Industrial Revolution.

With the year’s harvest safely delivered to the landlord, it was then time to figure out the rent. Because not only did that family have to hand over everything, they also needed to pay the landlord for the privilege of working the land and delivering everything they worked for over to the crown.

That left not a single farthing to buy food for themselves.

But the potato was hearty. It could grow anywhere. And it produced six tons of food every year.

So, they took their spades and dug those ridges into every inch of bad, inarable soil they could find, and they planted them.

The Irish don’t “love potatoes”; we had no choice but to consume them. There were no other options, and when it failed, the consequences were deadly.

By the time of the Great Hunger, Ireland was already beaten into submission. Cromwell, the Wolf Tone Rebellion, the Act of Union. There was no industry. No development. No Catholic representation. We couldn’t speak English. There was no point. No future. Why bother?

In the Ireland I grew up in, the scar of colonization not only marred the landscape, but led to the collective dissociation of an entire people by stripping it of its language, its culture, its will, and its ambition.

But there was one tradition we held onto with a grip of iron: artistic pursuits.

Through written word, poetry, and music, we found a medium for release, where the inner workings of our minds, our repressed emotion, our anger, could be unleashed in healthy ways, most often through the lens of horror.

Horror, specifically told through superstition and folklore, gave us a reason. An explanation why God let this happen. Because it couldn’t have been God, nor the Devil, for God has jurisdiction over those kinds of shenanigans. No, it was something else, something with its own set of rules and morals that made no sense to man or God.

The Irish were born into horror, we lived and breathed horror, so when people ask why I chose to combine Irish historical fiction with horror while steeping it in folklore, I tend to look at them blankly. “Are you serious?” The correlation is obvious to me: it’s the only way to explain an entire culture while allowing us to work through the trauma that we’re still dealing with today.

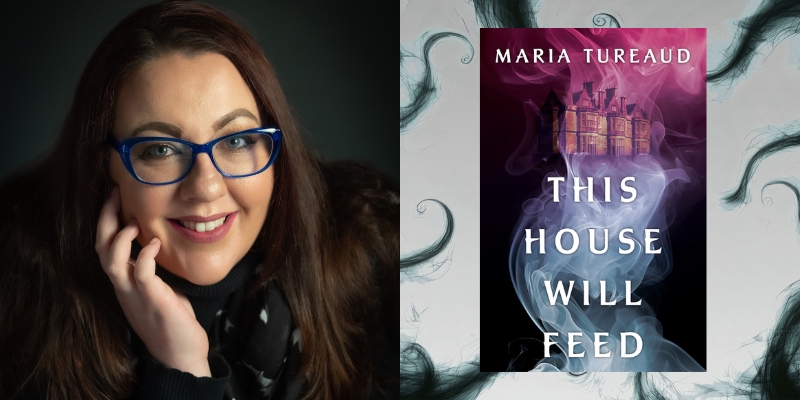

Writing This House Will Feed was certainly a form of therapy for me. It’s a study on grief and how we deal with darkness and death.

Against the backdrop of the Great Hunger, Maggie has blocked out the worst of what she’s been through. But when offered everything she desires by the supernatural forces that haunt a Gothic manor located in the Burren, County Clare, she needs to relieve those memories. She needs to face them, to discern truth from perception so that she can truly grieve and heal.

When we first meet her, she embodies the very core of what’s still demanded of Irish people by Irish people today: get on with it…aren’t you alive, aren’t there people worse off than you? And that, dear reader, is a symptom of generational trauma, a way that allows the collective to cope with the lingering effects of colonization.

But as she develops, and as the gothic horror of it all unfolds, Maggie learns to work through her grief: to be emotional, to allow herself to be angry, to rage, to scream, to cry. Because only when broken can we pick up the pieces of who we once were before putting ourselves back together.

In an abstract way, This House Will Feed is so much more than a Gothic horror. It’s a love letter to those who came before me and to those who shaped the person I’ve become. Is that a dark assessment? I’m Irish, so of course it is.

Today though, Ireland is changing. Mental health is taken more seriously, and the government has taken a stand against not only economic threats from foreign regimes, but also against superpowers who support the same kind of oppression and annihilation that we, ourselves, endured.

That fortitude lent me the strength I needed—the strength of the collective—to be able to put pen to paper and write This House Will Feed. Because though we’re grateful we made it through, that gratitude becomes toxic when we don’t face the trauma. And to finally free ourselves from the yoke of colonization, we need to face it in order to heal.

***