One of my favorite lines about conspiracy theories is that when the famous director Stanley Kubrick was hired to fake the moon landing, he was such a perfectionist he insisted on shooting on location.

That’s a funny one, but there are people who believe (maybe you) that Kubrick was hired by the government to film a fictitious moon landing and that he left six teasing clues in The Shining as proof he did.

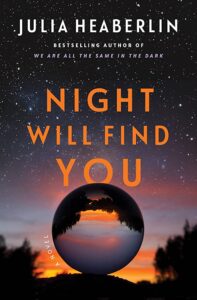

I learned all of this while researching conspiracy theories for Night Will Find You, a thriller about a missing girl that also examines our belief system—in higher powers, ghosts, science, psychic phenomenon, conspiracies—basically in things we can’t see or prove but believe anyway.

Our era isn’t especially fraught with conspiracy theories, even though it feels like it. People have been building conspiracies since Nero was accused of setting Rome on fire and playing the fiddle while it burned. Can we even prove Nero played the fiddle? Who knows? Who cares?

I can’t get behind the fake moon landing or the idea that the earth is a pancake. The conspiracy theories fostered by the likes of podcaster Alex Jones about Sandy Hook and the Holocaust are unspeakable. Unforgivable.

But I can build up a froth about the government, and the rich and powerful, lying to us.

This is the reason some conspiracies thrive in a “sensible” journalist like me—a legitimate lack of trust coupled with the problem that, sometimes, conspiracy theories turn out to be completely true. Yes, a long time ago, the Canadian government did hire a professor to create a “gaydar” machine so people who were gay could be identified and fired. In the ‘60s, the U.S. did secretly dose people with LSD in an experiment designed to achieve mind control.

And the odds were that the astronauts who landed on the moon were most certainly going to die on their mission. That’s not something the government told us until years after the fact. Americans would never have stood behind such doubt. The powers that be thought we needed protecting, or more likely, they didn’t want to be accountable.

Is this why the government won’t tell us everything they know about the manic UFO antics witnessed and reported by legitimate pilots? Why the stories about the flying objects shot down by the military just this past winter have simply dropped out of sight? Why the Pentagon felt the need to rename UFOS more elegantly to UAPs (Unexplained Aerial Phenomena)?

I have so many questions. Herewith, a selection of conspiracy theories I can get on board with.

Marilyn Monroe was murdered.

Why would she kill herself in the nude?

Why was there no glass of water by her bed at the crime scene if she swallowed a lethal number of pills?

Why did it take an hour or more before the LAPD was called after she was found dead?

Why would her housekeeper mysteriously begin washing the sheets she died on that morning?

And why did the beachfront neighbors of Robert Kennedy’s brother-in-law report that sand got in their pools because a helicopter landed and helped Kennedy escape his lover’s crime scene (he was seen at Marilyn’s house the day she died).

How much of the above is true? I don’t know for sure, but somebody does, and therein lies the frustration. A wish for justice. For fair play. In the case of Marilyn Monroe—and Princess Diana—no one, including me, wants to believe that someone who is extraordinary can die an ordinary and random death.

Whatever happened to JFK, it isn’t what the government has told us.

I’m a Texan. I stood in Dealey Plaza when I was eight years old and looked at the angle from the book depository window that at the time was marked with a big, dramatic X (until someone decided correctly that was tacky). I needed no forensics; I decided for myself that the shot was too tough to make. As an adult, I don’t buy that a magic bullet took a roller coaster ride through Kennedy and the governor of Texas and remained pristine. Even Lyndon Johnson didn’t believe in the single bullet theory. If that isn’t enough, I sat in a Chili’s restaurant with the late Jim Marrs, the author of the book on which Oliver Stone based his fascinating and conspiracy-laden JFK movie. Jim had offered to help me with some of my new thriller’s conspiracy theory research, and he conveniently lived in the small town where I grew up. His wife was with him at lunch that day, a lovely woman who hosted a book club for me once with cookies and deviled eggs decorated like black-eyed Susans. It wasn’t that Marrs, a New York Times bestselling author, journalist, and self-described “conspiracy factualist,” told me he was threatened by the government while writing the JFK book and that he was worried for his family’s life. It was that his wife confirmed it. That’s one degree of separation over a delicious cheeseburger, folks.

The Denver International Airport is just … weird.

The first problem—it was more than $2 billion over budget. Two billion. Where did that money go? OK, the airport is twice the size of Manhattan Island, but that number still gives plenty of life to the theories about underground tunnels and rooms nested in subterranean levels. For what purpose? There are many suppositions about that as well as the creepy ground-level art that greets travelers. One apocalyptic mural depicts a soldier with a gas mask and a machine gun. Grinning gargoyles loom over baggage claim. The red-hot eyed, 32-foot-tall blue horse sculpture, known as Blucifer to Denverites, rares up over the median of Peña Boulevard. The horse actually killed its maker in studio when a piece of it fell on him. The curse of the blue horse left such an imprint on me that the heroine of Night Will Find You is haunted by a vision of one that saves a friend’s life.

The fashion industry makes small pockets in women’s clothing so we will buy more purses.

This just makes sense. Why else am I unable to cram more than a credit card in my tiny pocket (that will fall out) if I have pockets at all? My husband, meanwhile, can tuck a wallet and keys and even a cellphone in his generous pants pockets. Like lemmings, women keep buying purses. The average purse retails for $160, and women have as many as nine to thirteen handbags in their closets. Some women pay as much for a single purse as it costs to buy a Tesla. We are hypnotized into believing we need different versions for summer, spring, winter, fall, work, casual, travel, weddings. We buy purses to the tune of at least $11 billion a year. We suffer spouses who ask, “Why do you need another purse?” It’s small pockets now, but the next thing you know, the government will start banning books and turn our world into The Handmaid’s Tale.

***