Last fall, when the BBC released Obscene: The Dublin Scandal, a podcast about an aristocratic Irishman’s deadly 1982 crime spree, there was a notable, if predictable, gap in the narrative. By then, Malcolm Macarthur, the notorious murderer at the heart of the story, had been out of prison for a decade, and though he was occasionally spotted in public—grocery-shopping, attending lectures at museums—he wasn’t among those interviewed in the show. “I knew that they had not been able to get access to Macarthur—that they had not, in fact, even been able to find him,” Mark O’Connell writes.

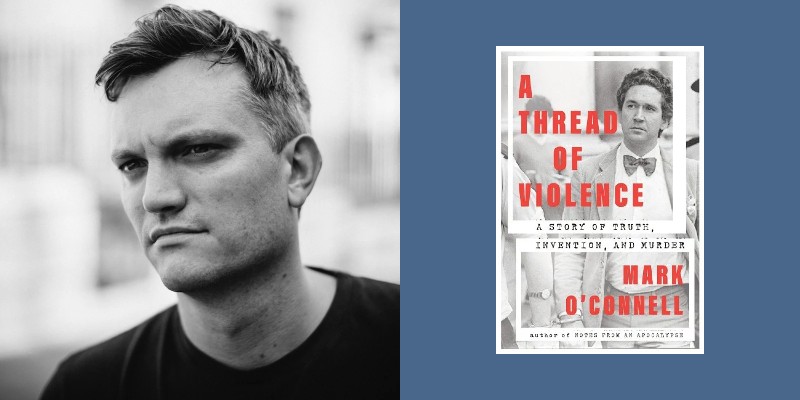

How would O’Connell know this? Because he’d been interviewing the elderly ex-con semi-regularly for a year. As O’Connell relates in A Thread of Violence: A Story of Truth, Invention, and Murder, Macarthur remains a subject of lurid fascination: “Among Irish people old enough to remember the summer of 1982, he is as close to a household name as it is possible for a murderer to be.” That July, the 37-year-old Macarthur was short of money, but instead of working, he decided to rob a bank. In need of a car and a gun, he stole the former from a nurse named Bridie Gargan, whom he beat to death with a hammer, and the latter from a farmer named Donal Dunne, whom he shot to death. When his heist plans foundered, Macarthur went into hiding with a friend, who happened to be Ireland’s top law-enforcement official. Attorney General Patrick Connolly, it turned out, knew nothing of his houseguest’s crimes, but the case was nonetheless a national spectacle. Macarthur confessed and served 30 years in prison.

In 2020, O’Connell began taking long walks, hoping to spot his fellow Dubliner and ask if he’d talk about the crimes, something he’d never done publicly in any detail. They met in 2021, and Macarthur eventually agreed to a series of interviews. I talked with O’Connell just before the release of his fascinating book.

Kevin Canfield: When you first approached Macarthur, you spoke to him for a while on a sidewalk, and during the conversation a stranger started taking photos of you two, then approached and swore at Macarthur. This must’ve reinforced, just as you were starting this project, how notorious he remains in Ireland.

Mark O’Connell: I’d been trying to find this guy for so long—and trying against what I knew at that point to be fairly steep odds to get him to talk on the record for the book. As I was talking to him, there were so many things happening in my mind, so many different emotions and reactions—one of which was just pure exhilaration that I’d finally found him. But yeah, that moment that you’re talking about was a real rug-pull, in lots of different ways.

Macarthur had just said to me (minutes earlier) that he rarely gets abused on the street. But this was a moment of very intense conflict—this guy was clearly very angry, and there was a kind of glee to his having encountered Macarthur. There’s something about a person like Macarthur in a city the size of Dublin—he’s strangely vulnerable, because he’s such an outsized villain in such a small city. And there’s a sense that anything can be said to this man, and almost anything within the bounds of morality can be done to this man. I found that moment destabilizing. So much of the book is about control in different kinds of ways, power dynamics and the relationship between a writer and a subject, and that was a really early intimation of that instability of control.

In 1982, when Macarthur was caught, the arrest happened at a building next to the one where your grandparents lived. So to a degree, this story has been on your mind for decades.

I have distinct memories of hearing about it as a kid, that this thing had happened in a building where my grandparents lived. So it always existed for me as this kind of myth or story that hovered around a place that I knew quite well as a child. As a person growing up in Ireland, it kind of does have that resonance—it exists as a kind of an urban legend, as much as it is a reality. I think it’s because he’s never spoken before, and so when someone doesn’t speak almost anything can be said about them, almost anything can be projected onto them.

I’m guessing that those facts—that he pleaded guilty, didn’t take the stand in a courtroom, hadn’t spoken about it publicly—made the Macarthur story even more interesting for you?

It did, but the book exists almost as a result of my naivety and ignorance. I’m not a journalist—I write for magazines, but I don’t exist in any kind of media ecosystem. So when I decided I was going to write a book about Macarthur, my idea was: Well, I’ll find him, I’ll chat to him, he’ll tell me as much or as little as he wants to tell me, and I’ll put that into a book. When I say naivety, I mean I knew that he had never been written about in this way before, but I didn’t realize quite why—because he’s out on license, which is not a thing that you have in America.

As you say in the book, that basically means that there might be consequences if he said something to the press that was deemed inappropriate by the criminal justice system.

He always understood that he was on kind of shaky ground talking to me. He’d never spoken to any journalist or filmmaker or documentary maker or radio person about his crimes before—for the reason that he has this kind of interdiction against speaking to the media. My status as a non-journalist was really what led him to feel: OK, there’s some wiggle room, I can talk to him (O’Connell).

How does he talk about his crimes? You use the phrase “grammar of displacement” to describe how he uses language in a way that distances himself from what he did, describing things in the second person, for instance.

A big part of my interest in Macarthur, and our relationship as it developed over the months that we were engaged in this, was to try to get him to a real place, to get him to say something real, to admit to something real in terms of his guilt and shame about what he did. So in a way it was quite frustrating to have these barriers erected linguistically between himself and the truth of what he did. But at the same time—as a writer, as someone who’s interested in how people talk and how language works and how we make sense of the world through stories—it was just fascinating to see this operating in real time. To see the way that he constructed his reality through language.

You write, “The moral imperative in contemporary writing about crime is that of centering the victims…And yet, the more I try this, the more wrong it feels.” How did you decide what, and how much, to say about the victims?

There are lots of books that do this brilliantly. I’ve been reading Gordon Burn’s work again recently, and he does that extraordinarily well. In my case, I felt that it would have been somewhat hollow. There are a few ways I came to that realization. One of which was I just spent a really long time trying to find the families of the victims and trying to get them to talk. They have talked in the past, but it’s been well over a decade since they’ve said anything publicly about their loss and the case itself. I tried to get them to talk, and they just don’t. Obviously, you have to respect that. And that led to me to think, in ways that I go into in the book, what it would it mean for me to tell their quote-unquote “stories” in this book. And I just really started to feel that it wasn’t my place to do it. They have a right to privacy. I think they have a right to not have their lives reconstructed in this larger narrative of Macarthur.

Macarthur is an intelligent man. He’s a reader, he’s very interested in science. You interviewed him at his home lots of times. Unlike you, he seems to have hoped that you’d become friends. How did you think about the relationship over time?

I definitely kept more of a distance. It was a strange, slightly contradictory thing—I spent more time with him by orders of magnitude than I’ve spent with anyone I’ve ever written about. But there was always a kind of formality, a formal distance between us. Partly that has to do with his personality, his way of being, and partly that has to do with myself and my own sense of uncertainty and discomfort. I never wanted to be too familiar with him. I never wanted to be just hanging out.

In a way, in talking to me to the extent that he did for as long as he did, that was a real gift. But there were moments where I would find myself chatting with him when it was difficult to square the person sitting in front of me and talking about string theory or whatever it might be with the actual reality. I would think of the moment of the murders themselves. Sometimes, I would look at his hands as he was talking and think: That’s the hand that held the hammer, that’s the hand that committed these brutal murders—this hand that’s gesticulating in the air.