During the early 1930s, Hollywood grew a large and ugly underbelly. Frank Nitti, the Chicago mobster, had his evil eye on Hollywood, with its drug addicts and homosexuals and rampant promiscuity, and he saw the potential for all kinds of extortion.

“The goose is in the oven just waiting to be cooked,” Nitti said.

The first worms in, the ones laying parasitic eggs in show business’s bowels, were a pair of seemingly mismatched hoods: a dapper racketeer named George E. Browne, and a roly-poly ex-pimp and Al Capone bagman named Willie Bioff, who had the lascivious grin of a cartoon wolf. Bioff’s name was pronounced BEE-off, but after he gained notoriety, some took to calling him BUY-off.

Browne was a quiet, reserved alcoholic, most often seen earlier in the day and in a finely tailored dark suit. Bioff was chattier, a close talker with a smarmy manner. They got their start bootlegging and pandering but the repeal of Prohibition killed the first vocation and the Great Depression slowed down the second. So, they had to improvise.

Browne and Bioff (B&B) started out extorting Fulton Street butcher shops, and other mom-and-pop stores, selling protection. Browne worked the gentiles, Bioff the Jews. They progressed to theaters. Pay me and nothing bad will happen. The threat didn’t need to be specific—Browne could be frightening, Bioff terrifying—although if a theater owner seemed slow on the uptake the menacing messenger might mention the “beatings” and “bombings” that had been going on.

Despite being a thug, Browne was a canny businessman. Why shake down theaters one at a time when you can score big with a whole chain of them at once?

Their first attempt at a big-time theater shakedown went smoothly. It was early 1933, and they targeted a chain of Chicago theaters owned by Barney Balaban, who later ran Paramount, and Sam Katz, who later became part owner of MGM. Like the Schenck brothers – the immigrant brothers who became powerful Hollywood moguls – Balaban and Katz were into pictures as well as theaters, starting in nickelodeons and producing flickers.

B&B extorted the chain for $25,000, under the official guise of collecting money for a local soup kitchen. A donation could prevent problems, Bioff explained. The pair of thugs were filled with optimism at their easy success, convinced that the owners would repeatedly pay to avoid violence on their property.

To celebrate, B&B took their loot to an illegal Chicago casino called Club 100, where they drank heavily, flapped their gums, and played roulette.

They were noticed by the casino owner, a surly hood named Nick Circella, who worked for syndicate lieutenant Frankie Rio. In fact, Rio and Circella were in the corner in the back, sipping espresso at the owner’s table, watching B&B as if they were exhibits in a zoo. They’d known these guys for years, especially Bioff, and knew his scams to be strictly door-to-door.

“Where do a couple of losers like them get that kind of cash?” Circella asked.

Circella reported the incident to Mr. Nitti, the man in charge of Chicago with Capone doing time. Nitti snapped his fingers, and the next day, B&B were escorted by Rio to Nitti’s twenty-room mansion. Browne and

Bioff were sweating through their stiff collars, convinced they were about to be whacked.

“Gentlemen, I have one question,” Nitti said. “Where did you get all the money?”

Browne explained that they’d collected protection money from a chain of theaters using a fake soup-kitchen charity.

Nitti hadn’t risen to the top of the underworld on ruthlessness alone, he was well educated and intelligent, and Browne’s expansive thinking gave Nitti an idea that made him smile.

The frightened visitors slowly realized that they were not about to die.

No one was going to blowtorch their armpits.

Nitti told B&B that they worked for him now. Mr. Capone, before his tragic downfall, had said the Outfit should grab a piece of Hollywood. This was the way to do it. Nitti knew Hollywood would be easy to extort. Bad things there tended to be swept under the rug. That meant money was exchanging hands.

It didn’t hurt that L.A. was corrupt through and through, the government and law barely more sophisticated than that of the Old West that Hollywood so loved. Nitti informed B&B that they were going to take theater protection to the next level, global rather than local.

“We are going to make millions, not thousands,” he said.

Nitti laid it out for them. It had to be done carefully. Nothing messy like bombs or guns. Better to have it appear that no crime was being committed. Do it through the unions. Control the unions and you could bring the business to its knees by threatening a strike. Nitti had made the scheme work in other industries. Control the unions and you controlled everything.

The plan had another perk. Nitti had been working on forming an allegiance with organized crime in other parts of the nation. This could solidify Nitti’s coast-to-coast influence. Nitti met with key mobsters in New York and Los Angeles, and formed a national syndicate, with one of its primary goals being a silver-screen skim.

Nitti installed Browne as president of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees union, commonly referred to as the stagehand union. IATSE was formed in 1893 to protect vaudeville workers. With Al Jolson and The Jazz Singer, IATSE was decimated, adapting slowly to the new sound era. Sound technicians organized elsewhere, IATSE fell out of favor and dwindled at one point to 175 Hollywood members. Installing Browne as head of IATSE was, for Nitti, the path of least resistance. Browne’s election was easily accomplished. One memo: “Mr. Nitti wants you should vote for Mr. Browne.”

As head of IATSE, Browne was able to execute a coup d’état at the projectionists’ union, and that turned out to be all the leverage they needed. The shakedown of the big studios commenced. Bioff was appointed Browne’s “first assistant special vice president” and, just in case, his “international representative.”

Bioff was the kind of guy who would pick his teeth with your fork, a perfect choice as the operative sent to “organize Hollywood.” As the operation commenced, everyone saw less and less of George E. Browne, who retreated behind his closed office door and reportedly quaffed a case of lager a day. It was Bioff—now in charge of Locals 37, 883, and 695— who did the legwork.

B&B increased union dues by $5, then pocketed every dime of it. They threatened a strike by the New York City projectionists. And that meant threatening Nick Schenck. Bioff had no qualms about visiting Nick at his office overlooking Times Square.

According to Nick’s testimony years later, Bioff began by bragging about himself, about his power.

“Now look, Mr. Schenck, I’ll tell you why I’m here. I want you to know I elected Browne president, and I am his boss. He is to do whatever I tell him to do. Now, your industry is a prosperous industry, and I must get two million dollars out of it,” Bioff said.

Nick sputtered with indignation. “Impossible,” Nick said. “I cannot do it. I can never do it. There is no reason in the world for it. You are crazy. How could that much money be taken out of the companies and why should the industry pay to continue in business?”

“Stop this nonsense,” Bioff said. “You know what is going to happen. You know you will have to pay me sooner or later. We’ll close every theater in the country which has producers in Hollywood. Within twenty-four hours we can close every theater in the United States. All we do is pull the projectionists. You’re shut down. You think it over. I’ll see you later.”

“I’m telling you, it is impossible,” Nick said.

After a few days Bioff returned.

“I’ve been thinking it over,” Bioff said. “How about one million?”

Nick’s eyes twinkled. Bioff had admitted a willingness to negotiate.

“Still impossible. It is simply too much money in one lump.”

On April 18, 1936, Bioff came back with his final demand.

“Maybe you can’t get up a million dollars at one time,” Bioff said. “I want fifty thousand dollars a year from Warners, Paramount, Loew’s, and Fox. I want twenty-five thousand dollars a year from the rest, and that’s final.”

“Give me a sec. I got to make a phone call,” Nick said.

He called his brother and business partner Joe, and they discussed whether to give in to the extortion. Joe suggested that paying the bribe could have tax benefits if they arranged it correctly. They were not novices at this sort of thing, they agreed.

“Okay,” Nick said, and Bioff grinned.

They arranged for the first payment. Nick made the initial payment himself, carrying a little bundle with $50,000 in it to a suite in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. Nick entered and dropped the bundle on the bed. He looked out the window and saw Sidney R. Kent, representing Fox, entering the building with a bundle under his arm. When both moguls were in the room, Bioff opened the packages and counted the money.

On his way out the door, Nick said, “Willie, I’m a guy who likes to get his money’s worth. No raises.”

Bioff flashed Nick an evil smile. “I’m certain you will find labor cooperative with management’s way of thinking during these difficult times,” he replied.

A year later Nick received a call from Bioff, and the drop-off was repeated.

By this time the tables had largely turned. The Schencks proved to be the superior businessman, masters at making lemonade out of the sourest lemon. They wrote off the payments to unions as business expenses to avoid paying tax on that money. To further discourage revenuers, Nick said the second payment was not going to be in cash. Instead, he would arrange for a friend of Bioff’s to sell film to the studio, and Bioff’s pay would come in “excess commissions.” They even upped their payments to the mobsters with the agreement that some of that money would be kicked back to them.

The Schencks quickly understood that a corrupt union was cheaper than a legit one. These guys took their cut, sure, but they weren’t filled with silly notions regarding fair worker compensation. Some have estimated that during the B&B era, the Schencks, between them, saved as much as $15 million in wages they didn’t pay. As Bioff later realized, he’d been turned into Joe Schenck’s bagman.

Nick, ever the real-estate expert, bought Bioff a big Southern California house with mahogany paneling and rare Chinese vases. Bioff had a library filled with rare first editions, even though he could barely read. Nick cleverly hid his payments in the Loew’s Inc. books.

When the studios had actual problems with the unions, they used mob muscle to squash it. The national syndicate was getting its bite of the Hollywood apple and yet everyone was happy!

Everyone, that is, except for the unionized workers. Hundreds of thousands of dollars were changing hands between the moguls and the projectionists’ union, but not a single dollar made it into the pocket of a projectionist.

Plus, while the squeezing of the moguls had provided a steady flow of income, the squeezing of the workers never stopped. All unions under mob control had to charge their members a two percent “union war fund” to “pay bills in case of a strike,” except there was no war fund and that money went straight to Chicago.

Nitti’s plan was to eventually rule every union in Hollywood. They were about a fifth of the way home when B&B encountered their worst nightmare: a fearless man with genuine scruples.

“I had Hollywood dancing to my tune,” Bioff later recalled.

But only until he took on the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) and, to his surprise, tough-guy tactics didn’t work. SAG’s president was another tough guy, actor Robert Montgomery, who throughout his career played some rugged characters, including the hard-boiled detective Philip Marlowe in Lady in the Lake.

But none of his on-screen personae compared with the courage he showed in real life when he stood up to Bioff, saying, “Not here you don’t.”

The beginning of the end for Bioff came on May 9, 1937, at a meeting held at Louis B. Mayer’s beach house. At that time IATSE and the Federation of Motion Picture Crafts were battling over which would serve as the umbrella group for Hollywood’s craft unions. The meeting was held to determine which of those unions would become affiliated with SAG. Joe Schenck was there representing Fox. Mayer repped MGM. Robert Montgomery and Franchot Tone repped SAG. Bioff represented IATSE. Montgomery and Tone laid out their demands. Bioff and Mayer then left the room for a private caucus and when they returned announced that the studios would recognize SAG, and SAG announced they would team up with IATSE. Montgomery was troubled by the Mayer-Bioff caucus. Why would a hood like Bioff be involved in making a studio decision?

Montgomery was curious enough to hire a private detective, who quickly reported back with details of the mogul-mobster conspiracy. Montgomery told both the press and the Treasury Department about the unwholesome relationship, and an investigation ensued.

Joe fell first. He was called in to testify unaware that the feds already knew about the union kickback scheme. He immediately perjured himself.

_____________________

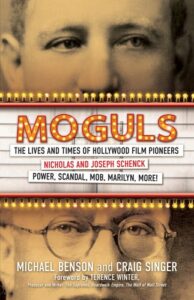

Excerpted from MOGULS. Copyright ©2024 by Michael Benson & Craig Singer. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, Citadel Press.