Some people have a calling in life that supersedes all else. Matt Murphy’s is justice.

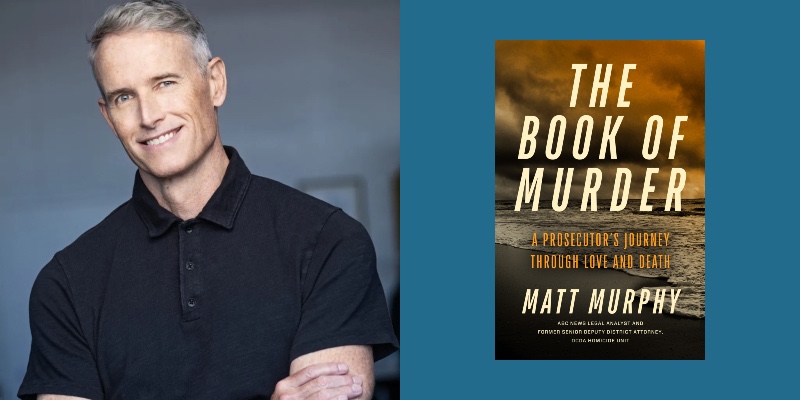

It’s a mission that he recounts in his new memoir, The Book of Murder: A Prosecutor’s Journey Through Love and Death (September 17, 2024; Hyperion Avenue)—a refreshingly candid account of professional service and personal sacrifice.

“I’ve never written a book before, so it was definitely a learning experience,” Murphy says, crediting the journals he kept at the time with helping to capture its rich detail and emotional resonance. “I didn’t want it to be your typical bubble gum true crime. Looking back was one of the fun parts about writing it …”

A graduate of the University of San Diego School of Law—he spent the summer of 1991 studying International Law and Comparative Law at the University of Sorbonne in Paris, receiving the American Jurisprudence Award in both classes—Murphy was actively recruited by private law firms, the FBI, and the Orange County District Attorney’s Office (OCDA).

Perhaps surprisingly, it was the latter—arguably the noblest, if least lucrative, of the options—that ultimately sustained him.

“It was just such an interesting interview,” Murphy recalls of his fateful meeting with OCDA’s Kathy Harper. At the end of their conversation, she offered him a paid clerkship.

“This was super coveted,” he says, noting that a top classmate could have had the position but opted to work elsewhere. “I decided that I was going to clerk … and I knew at the end of the first day that it was all I wanted to do.”

Murphy found kinship among his fellow law clerks, who he could envision becoming lifelong friends. He also found fulfillment in tasks such as painstakingly reviewing police reports and breaking down defense motions. But the real exhilaration came from making arguments in court; his very first appearance before a judge on a forfeiture case resulted in a resounding victory over two prominent defense attorneys.

“It was so much fun,” he says wistfully. “It was one of those rare experiences in life, but as soon as I walked into the building, I knew it was where I was supposed to be.”

Murphy took the Oath of Office as a Deputy District Attorney in December of 1993. He still remembers a sign that hung from a corkboard on the door of a Santa Ana courthouse, which read something like: The young prosecutor should never forget that their power over the lives of those they are about to encounter is directly inverse to their life experience and wisdom.

“Don’t be a dummy. You have a huge power over people’s lives. Do the right thing, you know?” he paraphrases, in reference to a prosecutor’s discretion in everything from filing appropriate charges to timely compliance with discovery. “Back in those days, that’s what it was all about.”

Murphy worked his way up through the Juvenile and Municipal courts before being assigned to the Felony Panel. He then graduated to the Sexual Assault Unit—a fitting appointment, given his undergraduate work at UCSB, where he organized a sexual assault program for incoming fraternity and sorority members that later caught the attention of prospective employers.

In 2002, after three and a half years spent prosecuting rapists and pedophiles, Murphy was promoted again, this time to the OCDA’s elite Homicide Unit. There, he worked cases along with the investigating officers, visiting crime scenes, attending autopsies, interviewing witnesses, and preparing cases for trial. While murder was rare in his jurisdiction, it was never mundane—and often attracted the attention of the media (resulting in appearances on programs such as Dateline, 20/20, and Crime Watch Daily).

But it was never the allure of headlines or news spots that motivated Murphy; rather, it was the prospect of getting justice for the victims and bringing closure to those left behind in the aftermath of violence.

“You get this sense very quickly of how bereaved the families are,” he says. “It is the absolute nadir of human grief when a parent loses their child … the only thing worse than a person losing a loved one to murder is when the killer gets away with it.”

And so Murphy devoted himself to ensuring that the guilty would be made to answer for their crimes, attaining an impressive string of convictions—even as his personal life suffered.

“I had this weird sort of double whammy,” he acknowledges, recalling two failed romantic relationships in quick succession—one of which he thought would end in matrimony and the other of which he soon recognized as a mismatch. “All of my buddies were getting married. I felt like it was a game of musical chairs where the music had stopped, and I was the odd man out.”

It was on an annual surfing expedition to Indonesia’s Roti Island that Murphy, surrounded by friends (and a deadly sea snake) yet feeling alone, had an epiphany.

“If I just sort of give up on this idea of a balanced life, and I just go all in on this, maybe I can do some good,” he recalls of his choice to assume a somewhat “monk-like” existence. “I decided to commit myself fully to the craft of murder and to learn everything I could about forensic science and DNA …”

Murphy continued to hone his skills, watching veteran prosecutors (“the masters”) in action, devouring classic texts like The Art of Cross-Examination, and solidifying relationships with the members of his team, many of whom were similarly devoted to the cause (and severely sleep deprived because of it).

“It’s a little unhealthy to say, but it’s almost like an addiction,” he admits, equating the championing of victims’ families and satisfaction of guilty verdicts to hits of heroin. “And I needed more and more to get that same high.”

As his confidence (and conviction rate) grew, so did the complexity of his caseload (which included taking on no-body crimes and Ripley-like criminals); eventually, Murphy took an interest in cold cases, some of which dated back more than thirty years.

“I started looking at cases that other people had passed on,” Murphy says, noting that the perpetrators were often known to investigators, but the evidence was deemed too thin to take to trial. “Detectives love when they have a prosecutor who has actual charging power, who is willing to role up their sleeves and dust off those old boxes.”

This all-consuming obsession led to long days and sleepless nights in which he and his colleagues would doggedly pursue new leads in old crimes, many of which benefited from advances in forensic science. One notable example is the 2010 conviction of infamous “Dating Game Killer” Rodney Alcala (soon to be revisited in actress Anna Kendrick’s directorial debut, Woman of the Hour), whose murders dated back to the 1970s.

“I had a lot of really good people who made me look good,” he says of his behind-the-scenes team, which gets its due in Murphy’s memoir (as do his mentors, co-council, and even a surprising number of defense attorneys). “I got to be the front man at the podium making the arguments, but I had such good detectives and forensic scientists, and I had the world’s greatest paralegal.”

The Book of Murder, then, isn’t so much a clap on the back as a celebration of the camaraderie and teamwork that went a long way toward proving that justice delayed isn’t necessarily justice denied.

“It makes me feel good that that came through. It really does,” Murphy says. “Because they are the unsung heroes, and they don’t get the credit they deserve.”

After seventeen years as the Senior Deputy District Attorney in the OCDA Homicide Unit (during which which he never lost a trial), Murphy made the decision to go into private practice, opening Matt Murphy Law APC. He also embraced the true crime community, and currently serves as ABC’s legal analyst, appearing on programs such as 20/20 to offer expert commentary and opinions.

“As a prosecutor, you’re supposed to educate the public. It’s a complex subject matter, and a lot of people don’t understand it,” he explains, citing the proliferation of social media as an example of how truth can be subverted by clickbait. “For me, it’s a great opportunity to educate people who are interested, and who want to know how [the system] actually works.”

From teachings and training to public speaking and presentations (including multiple appearances at CrimeCon), Murphy has become a mainstay in the public eye; it’s not only an extension of his previous career but one that helps to offset the costs of his current casework.

“A large part of my private practice now is defending police officers,” he says of the need to remedy unjust charges in the wake of anti-authority attitudes. “I’m not getting rich doing that … but it’s sort of my way of giving back.”

It’s a fitting sentiment for somebody who has spent his life prioritizing the needs of others over his own.

“I never got married. I never had kids. I did sacrifice that,” he concedes. “I think, for me, it was worth it. It really was. The need for justice is a real thing.”

Which is why Matt Murphy continues to answer the call.