I’m going to offer a few thoughts on why and how I went about writing Return of the Maltese Falcon. But, before doing so, I need to acknowledge a few books and their authors upon whose work I depended. Dashiell Hammett obviously towers over that list.

The 1961 paperback edition of The Maltese Falcon I read at age thirteen sported a Harry Bennett cover with Brigid O’Shaughnessy, Casper Gutman and Wilmer Cook portrayed in a then-modern manner. The publisher presented this great book as just another mystery novel, only twenty years after the John Huston film adaptation had been in theaters. I first saw Bogart’s breakthrough movie on a Sunday morning when I skipped church by faking stomach flu.

Two of the novel’s many editions were of enormous help to me.

First, the Modern Library publication (1934) includes an introduction by Hammett, already not writing much anymore, which shares insights on how the novel derived from the writer’s experiences as a private operative for the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, including suspects and other individuals he encountered on the job. He discussed reworking elements from short stories he felt hadn’t lived up to their potential. The author also essentially admits writing The Maltese Falcon without “the help of an outline or notes or even a clearly defined plot-idea in my head.” The notion that this seminal tough mystery novel could have been, and apparently was, produced in a written-by-the-seat-of-the-pants fashion is frankly astonishing.

The other edition I depended upon comes from North Point Press, appropriately enough a San Francisco publisher; it’s a handsome 1984 volume generously illustrated with full-page, mostly period, photos of the locations mentioned or implied in the novel. The twelve pages of end notes, printed in small footnote form, are packed with useful information. (The hard- bound edition of the book grows increasingly pricey, but the trade paperback—its size and cover art identical to the hardcover—still can be found reasonably at this writing.)

I also read the somewhat different version of the novel’s initial pulp serialization in editor Otto Penzler’s The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories (2010).

As a native Iowan who has visited San Francisco only a few times, I am no expert on the City by the Bay, so I was aided enormously by Don Herron’s The Dashiell Hammett Tour. Mr. Herron conducts a by-appointment-tour that I have yet to take, but I feel as though I already have, thanks to his guidebook (thirtieth anniversary edition, 2009). This is an essential work for Hammett fans, beginning with a fine biography of the man and the writer, taking up a quarter of the book’s pages, and worth the price of admission. Over the years, I have read every Hammett book-length biography I could find, and that’s more than a few; but the guidebook’s exceptional “brief” bio is the only one I referred to before I began (and during the writing of) this novel.

Like the North Point edition, the Herron guidebook is lavishly illustrated and written in an easygoing, accessible style as it delineates the various theories as to which locations are actually real ones. Hammett tends in The Maltese Falcon to rename the hotels but use the actual restaurants, sometimes thought to be the author trying to earn himself a free meal (a theory Herron dismisses). With its walking and driving maps, The Dashiell Hammett Tour is required reading for the Hammett enthusiast.

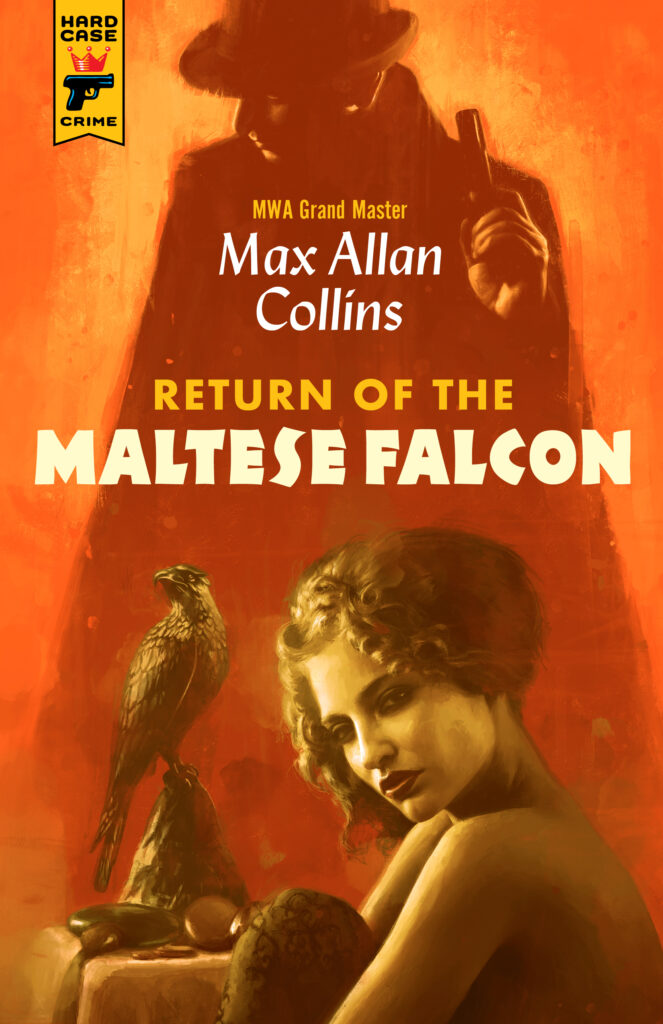

Article continues below cover reveal. Cover design by painted by Irvin Rodriguez.

The bedrock of the research for my long-running Nathan Heller series has always been the WPA guides, not just for Nate’s Chicago but the various cities he visits. The Heller novels put a private eye into the period in which the archetype for this sort of character was first created (largely by Hammett), and after which that character flourished in popular culture, a context in which my protagonist investigates real, often famous unsolved (or controversially solved) cases. It’s hard to imagine being able to write those books without the American Guide Series, and that also proved to be the case with Return of the Maltese Falcon. California: A Guide to the Golden State (1939) and San Francisco: The Bay and Its Cities (1940) were predictably helpful. Mystery fiction authority J. Kingston Pierce— knowing I was setting out to write this novel—generously sent me his excellent book, San Francisco: Yesterday and Today (2009), which proved most helpful as well.

That said, any inaccuracies and inconsistencies regarding the geography of San Francisco in Return of the Maltese Falcon are my own.

I chose not to revisit the film versions of The Maltese Falcon— the 1931 feature directed by Roy Del Ruth, somewhat forgotten today; a loose remake, Satan Met a Lady, in 1936; and then of course the classic John Huston-directed masterpiece in 1941— or any more recent works inspired by the book. (Joe Gores, a fine mystery writer and like Hammett a real-life private eye in his younger days, wrote a prequel novel titled Spade & Archer in 2009. A 2023 AMC television series, Monsieur Spade, apparently relocated the character to France.) My novel is strictly a continuation of Hammett’s original and does not incorporate elements introduced in any later adaptation (or in Hammett’s own later writings, for that matter). In writing this novel, I did not wish to be influenced in any way by anything other than The Maltese Falcon as readers first encountered it back in 1929.

To any who may think I am a buzzard picking at the Falcon’s bones, I can only say this is a novel I dreamed of doing for many years, and have been keeping an eye on the clock (as it were) as to the original’s public-domain status. I am something of an old hand at working in the vineyards of creators I admire, having taken over the writing of the Dick Tracy comic strip from Chester Gould for fifteen years, and finishing various works-in- progress of Mickey Spillane, including fourteen Mike Hammer novels, fulfilling the writer’s request of me in his last days.

My fascination with the work of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler and Mickey Spillane goes back, again, to around 1961. Two TV series sparked this trend—Peter Gunn (1959–1961) and 77 Sunset Strip (1958–1964)—though two series preceding those lit the fuse (Perry Mason, 1957–1966; and Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer, 1957–1959).

As an adolescent and then a young teenager caught up in those shows, I was aware that many, even most, of them had literary roots. Erle Stanley Gardner, Raymond Chandler, and Mickey Spillane had series derived from their popular books; even 77 Sunset Strip came from television giant Roy Huggins having started out as a Chandler imitator with a Stuart Bailey novel (The Double Take, 1946) and three novellas (collected as 77 Sunset Strip, 1959). Though not credited on screen, this TV afterlife is true of Dashiell Hammett as well, with the Peter Lawford-Phyllis Kirk-starring The Thin Man, 1957–1959.

My tendency in those days, and to a degree now, was to look at the literary source of any movie or television show that had caught my attention. When I was 13, that impulse is what led me to Hammett, Chandler and Spillane, the three writers who—in their respective decades—defined the private eye in popular culture.

Among the things that fascinated me then, and still does, is how different these three writers are in their approach and style. Hammett with his characters the Continental Op and Sam Spade is a former trained operative who brought a terse, informed eye to the crime story; Chandler, raised in Great Britain, with his slightly tarnished knight Phillip Marlowe raised first-person narration to a level rivaled only by Mark Twain in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884); and Spillane brought a rough-hewn pulp energy inspired by Hammett’s Black Mask magazine contemporary, Carroll John Daly, to new heights of popularity (and new depths of controversy).

What I have attempted to do in Return of the Maltese Falcon is honor the original novel and its author without writing strictly pastiche—allowing some of my native style to creep in while honoring the original’s.

When I reread The Maltese Falcon with writing this novel in mind—designing it more as a continuation than a sequel—I was surprised to see how subjective the Spade-centric omniscient narrator is. The objectivity of Hammett’s refusal to go into the point of view of his characters, including (especially) Sam Spade himself, is what makes the author’s approach so distinctive. He had written the Continental Op stories and two novels in the first person, after all; and only his later three (and unfortunately final) novels employ that technique, though some non-Spade short stories use it as well. This observation was freeing to me.

I also allowed myself, to a certain degree, to do more place description than Hammett. On some level, Return of the Maltese Falcon is a historical novel, or at the very least a period one. This hopes to honor Hammett’s style as well as stay faithful to the period in which the original was written—for example, women are often called “girls” and Sam Spade smokes to an alarming extent. To maintain a sense of the continuity with the original novel, I attempted as much as possible to operate within Spade’s world—the places he inhabits and goes, as well as the characters he meets, sometimes characters mentioned in Hammett appearing on stage for the first time.

Among Hammett’s stylistic quirks that I have followed is a tendency to always call certain characters—primarily female ones—by their full first and last names. He also frequently uses colons and not commas after “said”—I do this occasionally here myself. It’s part of what’s commonly thought of as Hammett’s terse style, but a writer who starts a novel with the omniscient narrator describing the protagonist as looking “rather pleasantly like a blond satan” isn’t really all that objective.

Sam Spade’s impact on popular culture and the private eye genre is remarkable considering the character only appears in one novel and three short stories. John Huston’s enduring film, with its iconic cast, cannot be underestimated in having extended Spade’s impact. But the character also went on to headline The Adventures of Sam Spade (1946–1951), an enormously popular radio show, as spoofy as The Maltese Falcon was straight. The money that series and The Adventures of the Thin Man (1941–1950) made, plus that of the Hammett-created The Fat Man (1946–1951), a combination of Sydney Greenstreet’s Casper Gutman and the Continental Op, freed Hammett from the need to make a living from his fiction, as did income from film adaptations.

It’s my hope that readers—frustrated by this great writer only giving us five novels, and no further Sam Spade ones—will enjoy and accept this effort as a kind of love letter to Dashiell Hammett and the private eye form.

***