Halfway through Among the Bros: A Fraternity Crime Story, investigative reporter Max Marshall recounts his meeting with a man who used to sell illegally sourced prescription drugs to fellow College of Charleston students. Describing a typical Saturday on campus, the former dealer spins a tale of drug-fueled debauchery that reads like a shooting script for a Cocaine Bear sequel. When he’s finished answering Marshall’s questions, the guy asks one of his own: Would Marshall be interested in hiring him and his employer—a Fortune 500 firm—to do some financial planning?

Marshall’s new book is a dispatch from the intersection of privilege, drugs and decadence. In 2016, Charleston police arrested eight young men who used their links to longstanding, almost exclusively white Southern fraternities to sell huge amounts of Xanax, cocaine and other drugs at colleges in the Southeast. The drug ring bought its own pill pressing machine and worked with an older man who supposedly ferried contraband for cartels. In 2016, a dealer connected to the ring was murdered. Drugs were scattered around his body.

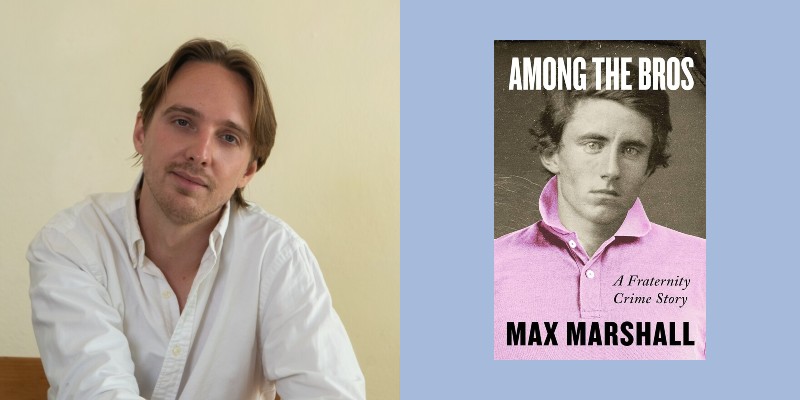

Speaking from his home in Austin, Marshall answered a few questions about his impressive, gripping book, the product of interviews with more than 120 people.

You first heard about these crimes after the Charleston police had a press conference where they displayed tens of thousands of seized Xanax pills, along with cocaine, cash and guns.

Yeah, I saw a lot of Xanax flying around when I was in college. I had a few friends who dealt Xanax and, more so, friends who were using it for anxiety. But pretty quickly, it was this party drug that was everywhere. So when I became an investigative journalist and I started doing crime stories, I wondered: Could you talk about this in a crime story? I googled “Xanax bust fraternity,” and the first result was this College of Charleston case.

You were in a fraternity. Is that what piqued your interest?

I did a three a three-year stint at Columbia. I’m from Dallas, and a lot of my friends were in these Southern fraternities. My mom was a University of Texas Kappa (Kappa Kappa Gamma), my dad founded the SAE (Sigma Alpha Epsilon) chapter at his college. My aunts and uncles are in Greek life. So yeah, it’s very much the bubble that I grew up in.

Has the relationship between drugs and on-campus life has changed in the last decade?

I think the big shift that happens in the 2010s, when it comes to college drug dealing, is the dark web. Up until pretty recently, if a college kid wanted to deal drugs, they had to tap into a supply chain connected to organized crime. With the dark web, all of a sudden you could stay in your dorm and have Xanax shipped to you in a Rob Schneider DVD jacket. That allowed these kids to traffic massive weights of different things without feeling like they were taking too much of a risk. But, of course, there was danger.

The main guy in the book, “Mikey” Schmidt, starts out selling fake IDs as a freshman. By the end of the book he’s making more than $10,000 a week selling drugs. How did this happen?

Mikey Schmidt showed up to College of Charleston from the Atlanta suburbs and joined Kappa Alpha. I think a lot of people underestimated him. He was 5-foot-7, and he talked in this funny stoner voice. But he has incredible emotional intelligence, he’s very funny and he’s willing to do things most people wouldn’t even conceive of.

In Atlanta, he started working as a parking valet at a nightclub, and he realized that if he dropped weed samples in people’s cup holders, they like that. He got plugged into the Atlanta rap scene, the Atlanta nightlife. By the end, he was bringing, allegedly, cocaine from cartel-connected sources from Atlanta to Charleston, and then he was taking Xanax from Charleston that these fraternity kids were pressing. He could basically be dropping weed, cocaine and other things off at fraternity houses around the Southeast.

To make these drop-offs, you write, he borrowed an idea from the drug dealer in the TV series Weeds.

He had a BMW, a Porsche, an Infiniti, but he also bought a Prius and put a baby on board sticker on it. The Prius never got busted, so I guess there’s some wisdom in Weeds.

And things got big enough that a subgroup of this drug ring bought a pill-pressing machine to make Xanax tablets?

It was less an organized ring and more like a multilevel marketing scheme, like Mary Kay or Cutco or Herbalife. Don’t sue me Herbalife. Not everyone in the ring knew each other, but there were multiple pill presses, and there was this group of guys producing at a pretty industrial scale. They would rent a beach house, bring in this large pill press, the kind that pharmacies use, and they could press out hundreds of thousands of Xanax pills using raw alprazolam powder that they ordered from China via the dark web.

Schmidt took a plea deal and got a 10-year sentence. But there were people who suffered far worse consequences. One guy, who was 23, had a bunch of pills supplied by this network. He got involved in a dispute with someone and ended up dead, right?

Patrick Moffly. His mom was a very prominent local politician, his dad was this big-time builder building mansions on Kiawah Island, SC for the international billionaire set. Patrick was dealing Xanax and other things for this ring. On the first Friday of spring break 2016, he was found murdered in his off-campus house with a Chipotle napkin on his chest covering the bullet wound, surrounded by hundreds of these GG249 Xanax pills that the pill press had made. (Two men were sentenced to prison—one for life—in connection with his murder.)

You remind us that Supreme Court justices, presidents, lots of lawmakers and CEOs were in fraternities. Fraternities are funneling well-connected young white men to influential jobs in the government and business world.

Part of the reason I wrote this book is that I felt there was something missing in the way we talk about fraternities. People think of fraternities in sort of a class-blind way, in terms of predominantly masculinity, and to an extent, whiteness. But to me, what was missing is that they’re both a product and a producer of the American elite. It’s not just a Southern thing. At Harvard or Princeton, they might call them final clubs or eating clubs. It does seem to be a way that people who went to a certain group of private schools come together. They hobnob and get drunk with each other, haze each other and then help each other for the rest of their lives.

As somebody who writes at length about criminals, how do you keep from glorifying them? Some of the guys quoted in your book aspired to be “the man”—basically somebody who gets rich while living dangerously. Will some people read this and think Schmidt was “the man”?

I can’t remember which filmmaker it was, but he said that you can’t make an anti-war movie—no matter how many horrors you document, there’s something about following that story that some people are going to watch and go, wow, that’s cool. There is a version of this book, I guess, where you can tell the reader, here’s what the moral is, here’s how you should feel. That’s not the type of book I was interested in writing. I think on some level you just have to trust a reader to respond how they’re going to respond.

The world has changed a lot in the last few years. Are fraternities going to have to change with it?

On some campuses, fraternities are, if not on the way out, then facing more cultural headwinds than they ever had. At smaller liberal arts schools or schools on the coasts, there’s a lot of student activism, reckoning with fraternity’s histories and their present actions. But in other pockets of the country, it’s an incredibly resilient system. There’s so much scaffolding around it in terms of alumni, prestige, endowment, legal support, lobbying. I’d be very surprised to see the elite fraternity world change too much.

So let me end with this amazing scene in your book. An ex-College of Charleston drug dealer details the debauchery from his school days, then switches into adult mode and tries to sell you financial services. Did you realize in the moment that this was a telling encounter?

He had just described the ways in which he would mix cocaine, Xanax, weed and vodka, and at the end of his story, he took out his briefcase and pitched me on why he should do my life insurance and be my financial planner. On one level, your reporter lizard brain is going, oh my God, this is a great scene. But then the other part of me thought, wow, this guy is really charming—should I consider having him be my financial planner? In a weird way, it was the most natural transition in the world. I think that connective tissue is something that’s missing when people talk about fraternities.