More than 100,000 people in the USA are on waiting lists for organ transplants. Each day 17 people die while waiting.

Advances in organ procurement and allocation have expanded the donor pool. For example (focusing on heart transplants, since I’m a cardiologist) in early 2020, doctors started to perform transplants using hearts from donors who had sustained circulatory-arrest deaths, instead of brain death. Similar to donors after brain death, post circulatory arrest donors have sustained irreversible neurologic injury. But unlike brain dead donors, circulatory arrest donors don’t yet meet formal brain-death criteria. This change has significantly expanded the donor pool. Today, 30%-50% of all transplants are from circulatory arrest donors.

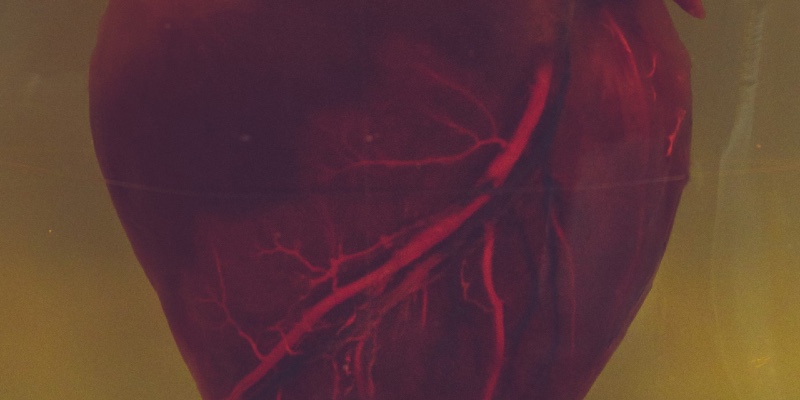

Advances in organ care systems have greatly expanded the viability and the scope of organ transplants. Today we have the “Heart in a Box” technology. Before this technology, the donor’s heart would be on ice in a cooler to preserve it during transport, and doctors had only four hours to get the heart to the recipient, which limited the possibility to provide matching organs across extended distance. If no suitable donor was available in the limited area, the heart would go to waste. Today doctors can revive the donated heart and make it beat again inside the box by perfusing it with warm, oxygenated blood, preserving it for up to 12 hours.

Despite the advances, the organ shortage is still a formidable problem. What complicates matters is the fact that for centuries ethical dilemmas have marred most medical advancements. From the sin of performing autopsies in the Middle ages, to the denigration of anesthesia, to the conviction that nothing could be introduced into human blood vessels, which forced a heroic doctor to perform the first heart catheterization on himself using a urinary catheter, many medical innovations endured an uphill battle. It shouldn’t surprise us that organ donation, which often requires the death of a donor, is also facing serious ethical dilemmas stifling life-saving progress and organ availability.

The challenge starts with the request for consent to donate. Today, the responsibility to obtain consent from the donor’s family and to evaluate the suitability of potential donors belongs to the Organ Procurement Organization. A doctor with a patient in desperate need of an organ is not allowed to approach a donor or his family directly. I strongly believe that organ donations would increase if the doctor helped the donor’s family to develop a connection with the recipient.

An even more controversial issue is that donation is viewed as a purely altruistic act, unburdened by external pressures and without any compensation to the donor or his family. Why should a donor or his family donate organs? From the goodness of their hearts (pun intended.) I’m a strong believer that we should compensate the donor’s family for organ donations. There are different ways to achieve this through hospital fund raising, private insurance, and private pay. What’s wrong with financial compensation, as long as proper patient-donor match and severity of illness remain priorities? After all, nowadays recipients do pay for sperm and egg donation. Why not for organs? Because of the National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA) passed by Congress in1984 to ensure an equitable allocation of donor organs and to (ironically) increase the number of organs available for transplantation. NOTA bans the sale of human organs for transplantation, with violations punishable by up to 5 years in prison and a fine of $50,000. A reason for the ban, is the past experience with the sale of blood, which led to problems with drug addicts selling blood-carrying diseases. But nowadays we have much better way to screen tissues and organs for infections. According to a prominent cardiothoracic surgeon I consulted, if half of the effort spent encouraging people to sign donor cards was spent to make organ donation safer, compensation to donors’ family would greatly increase organ availability. As it has happened in the past with other kind of prohibitions, the black market of organs is flourishing. Compensation for donation would help prevent illegal practices and unsafe transplant tourism.

In my novel I weaved into the plot and concretized several of these important advances and the ethical dilemmas they cause. I highlight in action the emotional turmoil faced by families of donors, who are thrust into a position of making a swift and agonizing decision about their relative’s organs. This reflects the tension between honoring the donor’s wishes and the family’s grief, compounded by the time-sensitive nature of organs’ procurement.

I delved into cybercrime linked to organ allocation systems, which can be exploited for profit, as concretized by the hospital hacking subplot and the misuse of donors’ data. I challenged the idea that donation should be purely altruistic, since compensation would alleviate illegal practices.

A good novel doesn’t openly proselytize. The author’s ideas have to be concretized through the actions of the characters and the events of the plot, so the reader arrives at the writer’s original idea by his own conclusions, after reading the story and may develop a personal opinion about these ethical challenges.

There are many more and greater challenges at the horizon for organ donation. Xeno-transplantation is in the process of becoming a reality. Today, gene-editing technology can create genetically-altered pigs which are bred and housed using infection-control measures and isolation in sterile environments, to provide organs, especially hearts.

Many object that using pigs and nonhuman primates for xenotransplantation research, or to grow organs, violates established best practices for animal care and welfare. This ethical challenge thrusts us into the discussion about whether animals have rights which supersede humans’ right to preserve and prolong their own life by utilizing nature and non-rational species.

I encourage other authors to concretize their views about these new ethical dilemmas through the actions of their characters and the plot’s events, to make people aware of the challenges patients and doctors face on a daily basis to promote life sustaining innovations.