From the time I began this column, nearly two years ago, I’ve been looking forward to interviewing Megan Abbott. I first became aware of her work in 2016, when I read The Fever over the course of a few days while holding my baby daughter, in the midst of a bleak election cycle which, as we now know, presaged many more bleak election cycles to come. I remember looking down at my daughter’s face and thinking, Oh no, is this really what it’s like to be a girl?

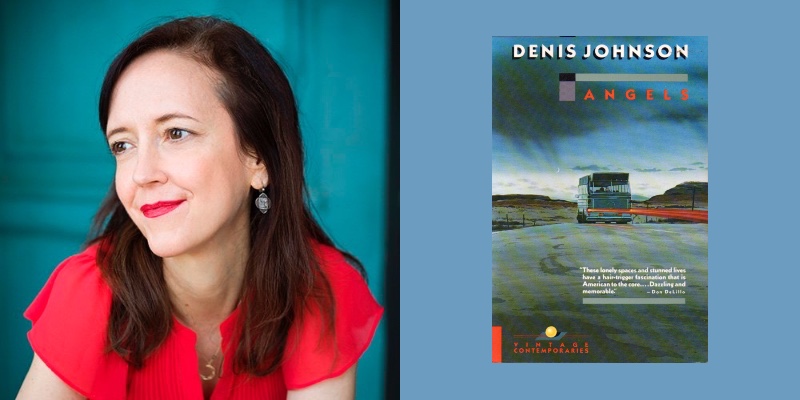

It’s a question that I should have already known the answer to, but there’s something about Abbott’s writing that makes women’s experience seem unnervingly foreign, even to women readers. Her ability to simultaneously employ and subvert the tropes of hardboiled and noir fiction turn the places and people we know the best into creatures in a funhouse mirror, at once familiar and nightmarishly strange. She is unquestionably one of the greatest writers in the genre, and I was thrilled to sit down with her recently to talk about another brilliant and unsettling novel, Denis Johnson’s Angels. It’s the story of two down-and-out characters, Jamie and Bill, who meet on a cross-country bus trip and end up joining forces with Jamie’s two small children in tow. Things do, of course, go horribly wrong, but not quite in the ways the reader might expect.

Why did you choose Angels by Denis Johnson?

In some ways, it was just happenstance. I’d just read the novel for the first time maybe the month before, and it was pretty revelatory for me. I’d read quite a bit of Denis Johnson, but not this one. When I mentioned it on social media, I heard from a lot of Denis Johnson devotees. It’s not as well-known as some of his work, but it’s just this emotional tour de force. It tore my heart out. I couldn’t put it down, and I couldn’t believe how good the writing was. It’s such a writerly feat to move from this very modest beginning to the operatic tragedy of the ending. It just knocked me out.

I’d only read Jesus’s Son before, and that was probably fifteen years ago. What else of Johnson’s had you read?

I’d read Jesus’s Son and Nobody Move. I remember when that one came out, because that was his noir novel. Then a couple of years ago, I read Stars at Noon and Tree of Smoke, which shares a character with this novel. They’re all so different, but they all feel like Denis Johnson, which is always true with the best writers. I loved how he could take on any genre and make it his own while also respecting the traditions of that genre. That’s not always the case, especially when “literary” writers write a crime novel. Sometimes there’s an air of condescension or they just get things wrong, but not Denis Johnson.

When I do these interviews, I’ve noticed that some people are happy to talk about labels and subgenres, and some people really resist it. I’m not sure which kind you are, but would you mind giving us your definitions of the crime novel and noir in particular?

Well, I can only say what it is for me. I guess to start, I’d say that only some crime novels are noir, but all noir seems to involve a crime, even if it’s incidental. To me, noir really has to do with the tone and the mood. It’s a kind of fatalism, which we certainly see in Angels—the characters feel like they’re trapped, and the reader does too. Their end is clear from the beginning, and you can see them heading right toward the abyss. But there’s also a kind of romance and glamor to it—a kind of seedy glamor that moderates the bleakness and gives it a kind of beauty. There’s also the fact that the characters tend to be the forgotten of the world. Socioeconomics may be against them, but they also have vices that are taking them down a dark path.

I’ve always thought of Johnson as a writer of literary fiction, perhaps because I associate him with Raymond Carver. How do you feel like he fits into that distinction between literary and genre fiction?

I do think those labels are kind of bullshit. I’m always very flattered when someone says to me, “Oh, your novels are so literary,” but I also suspect that those people haven’t read a lot of crime fiction. First of all, literary fiction is a genre. It’s just as formulaic as all the others. There are just as many tropes that we see recur in literary fiction. But also, when most people say literary, they just mean good sentences. It’s definitely true that Denis Johnson writes good sentences. He writes great sentences. He was a poet, so language is of primary importance to him. It may be that language is more important to him than plot, and perhaps that might be part of the distinction that some readers are making. On the other hand, he has this famous quote about sinners: “What I write about is the dilemma of living in a fallen world, and asking why it is like this if there is supposed to be a God.” To me, that’s why he’s so comfortable taking on these different genres. What he’s really interested in is this set of characters, and the stories are just engines he can use to explore their lives.

So when you say “this set of characters,” do you mean people headed toward a bad end?

Not necessarily, but they’re definitely all fringe-dwellers. They’re outsiders, the dispossessed. They’re not bourgeois, and they don’t abide by the same class constraints. They also have very little economic stability, which pushes them out of the possibility of a middle-class life even if they wanted it. They’re the Americans left behind by late-stage capitalism, who aren’t participating in the American dream because it’s not an option for them. You certainly see that in Jesus’s Son—there’s a whole steady train of them. And I think Johnson finds great beauty and mystery and pathos and poetry in those people.

I’ve never written a good poem in my life, but I’m a great believer that some of the greatest fiction writers, like Johnson, start as poets. Do you write poetry? Have you ever read Johnson’s?

I definitely don’t write poetry—at least not since college, when I wrote a series of Sylvia Plath ripoffs and my professor said, “I think you should try novels.” I can still be quite taken with a poem, but it’s not my natural language. I have read some of Johnson’s, and his poems feel very much like the novels. They show that agility with language and ability to surprise that I think makes the novels sing so beautifully.

Sometimes I wonder if poetry is the best training for writing those beautiful sentences you were talking about, because it makes a writer concentrate on language in such a particular way.

I think that’s right. Of course most poets don’t make good novelists, and most novelists don’t make good poets, but where there’s that intersection, I think it’s quite glorious.

You were talking a moment ago about the small, restricted lives that Johnson’s characters are generally stuck in. I know we don’t necessarily have to like fictional characters, but do you empathize with them?

I definitely do. What drew me into the book right from the beginning was the character of Jamie. You certainly worry for her as a reader, but she’s not living as a victim. She’s so vivid and vital and alive, and you can tell how much Johnson loves her and admires her resilience, her ability to keep going. If I were Jamie’s social worker, I might point out that she also makes a series of poor choices, but she’s just trying to live her life. You could say, “Oh my God, the things he has her go through in this book are catastrophic.” But you can feel his love for her, and that makes you love her too.

It’s similar with Bill, who is so shallow in his interactions with people at the beginning of the novel. When you meet him, he’s just out for a good time, and then by the end of the book, he’s this massively tragic figure. Johnson’s magic is that you feel connected to these characters no matter what. There’s an intimacy to the way he writes that’s kind of like a magic trick. It’s like you have your hand over their heart the whole time.

I love that. As you’ve said, we move to this deceptively simple meeting at the beginning of the novel to the almost operatic end where Bill is awaiting execution on Death Row. What do you think of the ending?

In some ways, it’s a classic noir move. The Postman Always Rings Twice ends on Death Row. The film of Double Indemnity is similar too, but in that one, you have a pretty good idea of where it’s going from the beginning. Angels starts with almost a meet cute, dirtbag-style: Jamie and Bill are on a bus, they start drinking beers, they’re chatting and she’s ignoring her kids. The beginning reminds me of another writer who plays with genre and has an immaculate voice, Charles Portis. Because of that tone, you think the novel is going to be much funnier than it is, but all the funny turns out to be in the first twenty minutes. It’s all meticulously orchestrated. It’s not just a matter of money and a woman, as with James M. Cain. There is money, and there is a woman, but the crimes are much more complex, and you don’t even meet some of the main characters until the last seventy-five pages of the book. I’ve read that it took Johnson twelve years to write the book, and it’s a bit of a mystery to me how he conceived of this structure. You feel like you’re in a road novel at first, and then it turns out you’re not at all.

I always read the Amazon reviews before one of these interviews, because I’m curious about what people are saying who may not be committed readers in the genre. One of the people who reviewed Angels was really mad that it turned out not to be a road trip novel.

Sounds like a classic Amazon review. I’m surprised they didn’t say Why isn’t this woman taking better care of her children?

That came up too. There was lots of hand wringing. I didn’t realize that Johnson took twelve years to write the book.

Yes, that was in an appreciation in the New Yorker after he died, but I don’t know much about why it took him so long. But I think it’s no mistake that the structure is so complex and sneaky and majestical.

I love the word sneaky here. There were definitely times when I thought, Does he not know what he’s doing? But I wonder if it’s that he’s skipping so many of the beats that we’ve come to expect.

Yes. He puts in all the parts that you leave out and leaves out all the parts you put in. He’s deconstructing the genre at the same time that he’s embracing it.

When I was Googling the novel, I found this piece by David Foster Wallace from Slate in 1999, where he said that he thought Angels was one of the best overlooked novels since 1960. (Of course they were all by white men.) I wonder if it’s that deconstructive element that Wallace is responding to.

Probably that, but also the playfulness. And there’s a lot of paranoia in Johnson’s work, which you can also see in Wallace’s—this sense of unseen forces moving the characters around. There’s also a feeling of America turned on its head. Even though they’re different ages, they’re both coming out of the counterculture in some way, and they’re both working out some feelings about America. You see a lot of anger at institutions, and both of them play with form, and they share a kind of absurdist approach to life. It makes sense to me that Wallace would have liked him.

You write for the screen as well as writing fiction. Can you imagine Angels as a movie?

Boy, it would be a tough hang. I would be there for it, but I’m not sure I would want to adapt it. One of the big risks that Johnson takes in this book is that the last fifty pages or so take place almost entirely within the minds of the characters. It just becomes so interior towards the end. I don’t know how you would dramatize that in film, other than maybe in a very avant garde way. You’re trapped in the psyche of these really fucked up people. I guess I can’t see it as a movie, but I’d love it if someone else had a real sense of how to bring the novel, especially that last section, to life. Paul Thomas Anderson could do it, maybe. The question would be, how do you convey that emotional interior experience of the characters once they see where they’re headed?

In the New York Times, Alice Hoffman described Angels as a novel about people “who slip helplessly into their own worst nightmares.” This description seemed particularly apt to me—when reading, I felt as if I was trapped in the nightmare too. Did you feel that way? How does he do that?

I think we have the feeling that the walls are closing in, and that’s definitely nightmarish. That’s one of the reasons this is a book for writers, because you’re fascinated by how he pulls it off. After Jamie and Bill are split apart, they both become more and more constrained, and there’s a kind of fatalism to it. You start out with the big expanse of America in front of them, the possibility of the road, a kind of Jack Kerouac vibe, and then by the end, you’re trapped in that cell.

We’re probably not exactly selling the novel to readers of this column!

Maybe we are, since they’re CrimeReads readers. It’s a fast read too, which I think works in its favor. First because it would be hard to be trapped in that world much longer, but also you read it very quickly; you’re propelled along. Then it turns into the worst amusement park ride ever, where you’re careening into the abyss. Your experience as a reader mimics the experience of the characters, where we’re living day to day, and then we take a couple of wrong turns and have a little bad luck, and suddenly you get this terrifying feeling that nothing can stop what’s coming. Again, it’s a great subversion of a classic noir trope. In a more traditional noir, Jamie would be the femme fatale and Bill would be the patsy or the dupe, but that’s not what Johnson does with them.

I agree. I felt like Jamie had more humanity than any other character in the book. In general, do you find that subversion of noir tropes to be effective? In a sense, is turning those clichés on their head more noir than noir?

Yes, because it’s much deeper. When you’re reading a kind of superficial or clichéd version of noir, you can still have a good time, but there’s a hollowness to the exercise. That’s definitely not something you feel here, because the characters are so real and vivid to us, and their world is too, that world of bad choices. Or that’s not even the right way to put it, because they don’t have any choices. Johnson lived on the fringe for a long time, and he knows that world, and he knows it’s not about choices. In that kind of situation, you have to take any little bit of joy that comes your way. If you have a chance to sneak some beer on a bus with a handsome man while your kids are sleeping, you do it. He understands the importance of having even that little bit of agency.

The Amazon reviews I read were also very critical of the title. What does it mean to you?

I think there’s a lot of play in that word, Angels. It’s purposely non-specific, as all good titles should be. I definitely wouldn’t call it a Christian book, but there’s a deeply felt faith hovering in the atmosphere. I think it’s Johnson’s faith in these lost people, in their humanity. I don’t want to spoil it for people who haven’t read the novel, but there’s a moment at the end of Bill’s last scene that made my cry. It was so unexpected. Another sign of Johnson’s mastery is that we realize then that he’s been holding back this moment the whole time, and we had no idea it was coming. A contemporary writer who also does that is Willy Vlautin. He also writes about the dispossessed, people who are one bad break away from real trouble. They’re trying to keep their fists up and also to protect their hearts, so that one moment where Bill really reveals himself is really devastating.

Is there anything you learned from this novel that you might apply to your own work?

It’s a great reminder of how character is story. When you write crime fiction, you can really get caught up in plot and trying to make things work, and I always need to be remembered that I have to follow my characters and see where they take me when I start writing. In this novel, the choices that surprise us the most are the ones that feel the most right. Let’s face it, none of us behave in expected ways in real life either. I think about that a lot, and also the wildness of his language. I can’t write a sentence like Johnson, but he makes you want to try and just go harder. Sometimes you think I don’t want to make this too dark, or too grim, and then you read Denis Johnson and you’re like, fuck that. You have to go where the characters take you.