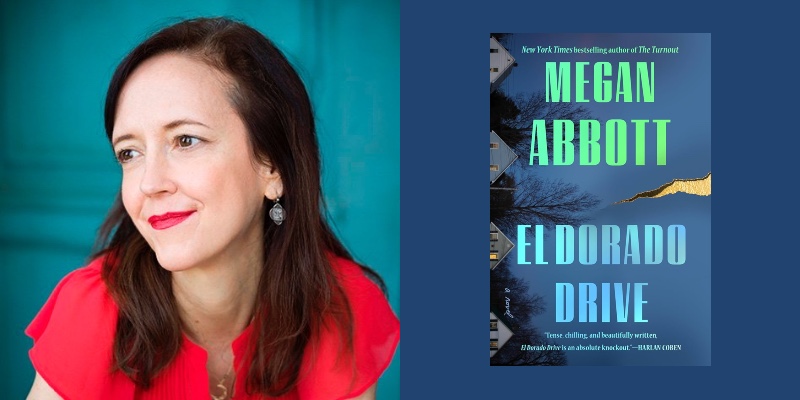

In Megan Abbott’s suburbia, there are always darker forces at play. In her new novel, El Dorado Drive (G.P. Putnam, June 24, 2025), a feeling of loss and decline permeates the once prosperous community of Grosse Pointe, Michigan, the author’s own hometown. The auto industry has lost its sheen. The country clubs are hotbeds of anxiety, stirring up questions about who lost a job this month, whose bills are past due. A group of women in the community have turned to one another for support. Financial support, in the form of a shadowy investment club that purports to lift up and empower women. In other words, it’s the perfect setting for a simmering, evocative noir, a quintessential Megan Abbott story. I caught up with Abbott recently to discuss criminal conspiracies, suburban ennui, and why neither of us can seem to stop writing party scenes.

Dwyer Murphy: How did you end up deciding to finally write about the suburbs of Detroit?

Megan Abbott: In some ways, I thought I’d never explicitly write about my hometown. I’m not sure why. Maybe because of the self-revelation involved. But I got really interested in suburban women who got caught up in pyramid schemes and multi-level marketing schemes (MLMS). A lot of them rose during the pandemic and, prior to that, during the last recession. I kept thinking about these areas that were once securely middle or upper-middle class, or even affluent, and it made me think about growing up in Grosse Pointe in the 1980s, and how everyone I knew had a parent who had worked for the big auto companies, or ancillary to them. It was this period of decline. A feeling that the sun was setting on the empire of Detroit. It seemed like a perfect setting for a story about women getting caught in these schemes. Women who grew up imagining a very secure life for themselves; now they’re in middle age, and they have to figure something out. It all seemed like I should definitely make this Grosse Pointe.

Dwyer Murphy: Did it feel different, writing about your hometown, actually using its name?

Megan Abbott: Memories of your childhood are the most vivid you ever get. I could just imagine walking into some of these restaurants and department stores. It felt like I was there. It had this piercing quality to me. Or I could picture the Hunt Club still. It’s different now, but when I was growing up it was the horse girl country club. Grosse Pointe was a town of competing country clubs. I had such memories of that place, from girl scout visits and having friends going there, I ended up having the main character work there.

Dwyer Murphy: Can you tell me more about horse girls, and how they factor into the story?

Megan Abbott: People in the past have told me I should write a horse girl book, and I haven’t yet, but I feel like I’m dipping into that. I was not a horse girl. I couldn’t have afforded to be a horse girl. Some girls who can’t afford it find a way to make it work – that wasn’t me. But I loved horse books as a kid. And horse girls fascinated me, the way they seemed very apart from other girls. They had their clothes, the way they broke down their bags. They were always going off to horse camp and competitions on the weekend. It wasn’t even snobbish. This wasn’t the equestrian kind of horse girl. They just had this aura of exclusivity. The way they talked to the horses. It all seemed glamorous and exotic to me. It felt like I had to place Harper, the main character, there. And I wanted to write about what it would be like to be a horse girl when the money is gone, when those dreams go away.

Dwyer Murphy: How did you devise “The Wheel,” this investment scheme the women get caught in?

Megan Abbott: I’ve always been interested in MLMS, then I found these other schemes, where you’re not even selling anything. In some ways they’re less legitimate, because there’s no product. I mean, you’re not even selling people bad essential oils. A lot of them go back to the Sixties and Seventies. There was one scheme called the airplane game. Another I read about was in Connecticut – a “gifting table” – where one of the women involved was murdered. There are so many schemes like this. You pay in, you recruit, you give the gift to the top. I got really into them. I found some guidebooks and manuals – documents that were entered into evidence when these schemes were prosecuted. For a writer, those documents are gold. You get to see entirely how they operate: the secret language, the code words. That was when I felt like I entered David Mamet land. There were all these ways they would use language to skirt IRS gifting rules, to avoid the suggestion of illegality. It’s fascinating to see how people convince themselves this is okay. The manuals would instruct women: ‘don’t say invest, say gift.’ And they would use the language of feminism. ‘Women investing in other women.’ That seemed particularly insidious to me.

All the moral skirting of the issues at hand felt so rich. Really, the schemes are based entirely on recruitment. So, like all pyramid schemes, the only people who make money are the people who come in early. You’re never going to be able to recruit enough.

Dwyer Murphy: Did you have a conspiracy corkboard with profiles of all the women?

Megan Abbott: At one point I had an elaborate way of labeling the different levels of the scheme, but it got so complicated I lost track. I had to simplify. You’re describing something that’s intricate by nature, so that people can’t figure out what’s legal or illegal. I couldn’t stop reading about how they all operated. By the way, the first rule in my pyramid scheme would be to not create a manual.

Dwyer Murphy: I did enough doc reviews as a young lawyer to be forever wary of putting things in writing.

Megan Abbott: I kept thinking about Goodfellas, which was a secret influence on this book, how Paulie (played by Paul Sorvino) never talks on the phone. Everyone has use payphones and talk to somebody else who reports to him.

Dwyer Murphy: What are the other secret influences on the book? I try to remember to ask you that whenever we talk about a new book because you always give me surprising answers.

Megan Abbott: On one level, this book involved a lot of plugging into WASP America and the nostalgia for that culture in its waning days. There was John Cheever, of course. And because the book is set in Grosse Point, The Virgin Suicides was on my mind. Eugenides is just a few years older than me – that book is really about my childhood. It’s a very different subject matter, but WASP world.

The other piece was really Glengarry Glen Ross. I did an early Mamet deep dive. And I was researching post-RICO organized crime networks. I really wanted to think of this as a criminal network. So much of the book is about family drama, but it’s enmeshed in criminal activity. I wanted each to be a red herring for the other.

Dwyer Murphy: I wanted to ask you about the opening scene. There’s an elaborate set-piece at a graduation party. I thought it was remarkable. It set the scene so vividly and threw us into this world.

Megan Abbott: The graduation party was so clear to me. I was very much thinking about these women at the age of becoming empty nesters. One, because they’re going to have to pay for their children’s college. And two, because being an empty nester creates the opportunity to reinvent your life.

A graduation party creates a lot of nostalgia. People are thinking about their own days in high school. So much of this book is about this complicated and rather dangerous nostalgia for a past and a community that’s gone forever. The sisters in this book had a terrible childhood, but they have nostalgia for it, because it’s this lost world. It’s like the Roman Empire: you lose it slowly and then all at once. This is the ‘all at once’ period.

It was also an excuse to write a party scene. I think we’ve talked about that before. I’m always looking for an excuse to write a party scene. This book is a series of parties. I think there are seven of them in there.

Dwyer Murphy: I got a note the other day on a project pointing out I had written three party scenes in a row. But honestly, I always just want more. Why do you think you’re drawn to party scenes?

Megan Abbott: It’s sort of like dream sequences: these things I can’t get away from. I suppose if I’m honest they feel very cinematic to me. And for me, the first big book of literature was The Great Gatsby. Also, in this book, there are more characters than I usually write, so it’s a way to bring everyone together. I wanted to create this ecstatic revelry that felt a little scary. All parties have that in a way. The energy of a party develops a life of its own. There’s something so mysterious about how a party works.