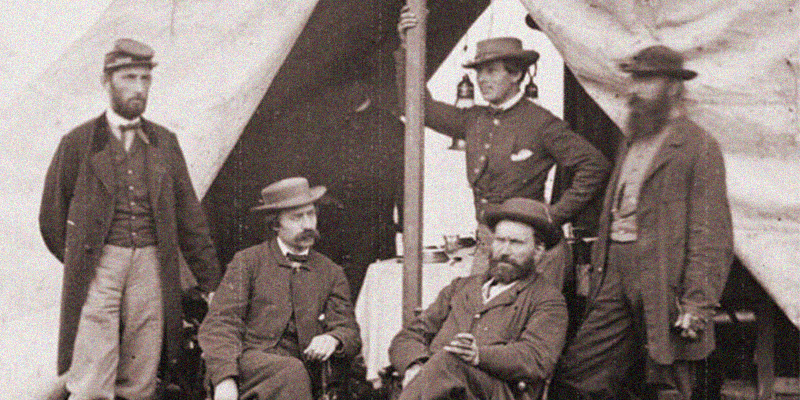

Allan Pinkerton is a storied figure in the American imagination. Most know his agency for its violent anti-union mercenary work, but few realize that Pinkerton was an Abolitionist, as well, who ran a stop on the Underground Railroad and headed Abraham Lincoln’s secret service during the Civil War.

He also wrote true crime books. In them, Pinkerton recounts his detective agency’s exploits, including several about the first woman detective in the United States, Kate Warne. Pinkerton was highly unconventional for hiring her. While more and more women were entering the work force in the 19th century, which jobs were considered “suitable” for women was a major point of contention. Detective work, with its proximity to cons and criminals, was definitely not.

My new novel The Widow Spy follows Kate Warne during her time as a Pinkerton detective and Union spy. In telling her story, I drew on Pinkerton’s “true crime” books as well as other historical documents. Pinkerton’s writing is an incredible window through time, offering a look at not only past views and values regarding society, women and detective work, but also how crime writing has changed.

Interested in the evolution of the detective genre? Here are five original Pinkerton stories to check out.

1 & 2: The Somnambulist and the Detective, The Murderer and the Fortune Teller. (1875)

This two-story volume features operative Kate Warne at her most adventurous. In The Somnambulist and the Detective, she goes undercover to catch a murderer. During the case, a colleague disguises himself as a ghost to frighten the primary suspect into confessing.

In the Murderer and the Fortune Teller, Pinkerton is hired by a sea captain who suspects his sister and her lover of dirty dealings. Kate poses as a fortune teller to entrap the pregnant sister into giving testimony against her murderous lover.

In the book, Pinkerton describes his choice to hire Kate Warne:

Previous to the early part of 1855, I had never regularly employed any female detectives . . . My first experience with them was due to Mrs. Kate Warne, an intelligent, brilliant, and accomplished lady. She offered her services to me in the early spring of that year, and, in spite of the novelty of her proposition, I determined to give her a trial. She soon showed such tact, readiness of resource, ability to read character, intuitive perception of motives, and rare discretion, that I created a female department in the agency, and made Mrs. Warne the superintendent thereof.

(Warning! There are references to fortune tellers and Romany culture in this last story that are based on harmful stereotypes.)

A primary source for The Widow Spy, this book recounts Pinkerton and his detectives’ spy craft during the Civil War, including Kate Warne’s pivotal work foiling a plot to assassinate Abraham Lincoln. It also recounts the work of another key woman detective, Hattie Lawton, who worked undercover in the South and narrowly escaped capture by Confederate soldiers.

(Warning! While Pinkerton was an active part of the anti-slavery movement, he employs some words and characterizations of people of color that were common at the time, but inappropriate today—and harmful in any period.)

4. The Burglar’s Fate and the Detectives. (1883)

This book follows several detectives working as a team to discover the culprit behind a bank burglary. It is a testament to prescribed gender roles of the period: faced with adversity, men “bear up manfully” and women swoon. That said, in a subtle subversion, a young woman (recently recovered from a swoon) offers smart and detailed observations that prove crucial to solving the case.

This compendium describes all sorts of criminals and criminal behavior from pickpockets and train robbers to confidence games and blackmail. It is intended as a classification guide for professional detectives and contains dozens of short vignettes from the agency’s archives. If you have ever been curious about the ins-and-outs of 19th century lock-picking, steamboat thievery or counterfeiting—this is a must read.

***