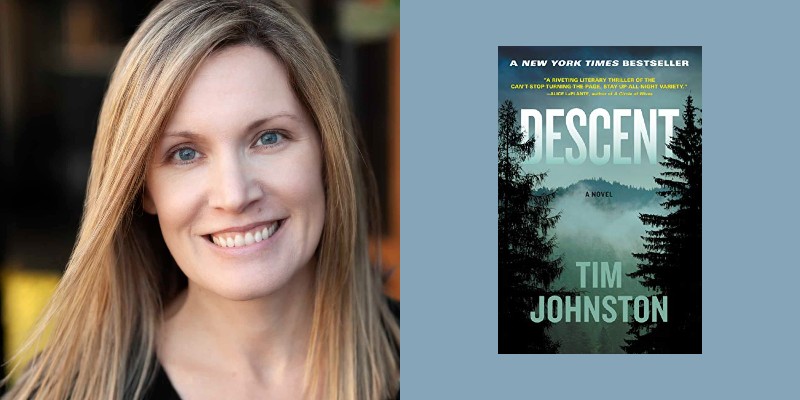

When I began this series for CrimeReads, I imagined myself reading a lot of Raymond Chandler, Dorothy Sayers, and Chester Himes. That was fine with me; other than a brief Agatha Christie phase in middle school, I’d never spent much time on the classics of crime fiction, and I looked forward to hearing what writers I admired had to say about them. What I didn’t anticipate is that I’d also be introduced to novels from the past five or ten years that I’d somehow missed or overlooked. Descent by Tim Johnston—a tense, complex, and beautifully written literary thriller—is one of these.

And who could be a better guide to the classics of the modern day than Megan Miranda, author of All the Missing Girls, The Last House Guest, and the forthcoming Daughter of Mine? I’ve long admired Megan’s work for the way it combines the structure of a fast-paced thriller with a literary sensibility and nuanced characterization. (It goes without saying that her books are also insanely fun to read!) It was so much fun talking to her about another novel that combines elements of crime and literary thriller, while telling a profound and sometimes disturbing story about the darkness of the human heart.

Why did you choose Descent by Tim Johnston?

When I think back to books that really resonate with me, this was the one that came to mind.

I might not remember every plot point, but I remember so strongly the journey that this book took me on, and it’s one that I found myself recommending to people over and over for several years after I read it. It was just stunning on several different levels. I’m drawn to books that have an external mystery, but also a mystery inside the characters, and this is a book that did just that. Also I love books that are set in the wilderness, and that setting was such a major element of the novel.

The novel begins with the Courtland family, who have taken a trip from Wisconsin to the Rocky Mountains before their daughter Caitlin starts college. While out exploring the mountains with her younger brother Sean, Caitlin is abducted and Sean is badly injured. What does this dynamic and dramatic opening do to set up the story that follows?

It just sets you up immediately. You know that their lives are about to change dramatically, and they do. But it just takes such a different turn from a stereotypical missing person story, because the timeline stretches over the years, and the reader really gets to see the depth of the impact on this family.

This novel switches back and forth frequently between characters, but the focus is on Grant and his children, Caitlin and Sean. Why do you think Johnston chose to concentrate on these particular points of views to tell the story?

I think it’s fascinating how the same incident can happen to a group of people, and yet there are so many different paths and responses that the characters can take from there. It’s so interesting to see how these different people are impacted by the same event—whether they blame themselves, whether they wish they could go back and change something. We get to see how the same trauma affects different members of the family in different ways.

This novel is often described as a “literary thriller.” What does that term mean to you?

I struggle with these genre categories too, but I’m usually a big fan of books that have that designation. For me, it signifies that it’s not just an exploration of an external mystery, but that there’s a journey into the main characters’ internal states as well. I don’t know if that’s the way other people mean it, but the feeling I get when I read those types of books is that it’s going to be a suspenseful story, but it may also take some side paths along the way.

Based on reader reviews, some readers find this to be slow-paced. I love novels that take their time, so it didn’t bother me, but it’s always a risk when you’re writing a book that will be marketed as a thriller. How do you think about pacing in your books?

I’m not somebody who is a deterred by a slower pace. I actually really like sitting in characters’ heads for a while. As a writer, though, I think that pacing comes from different elements of tension. There’s the external plot, the danger closing in, but there’s also the tension between characters and what a character doesn’t want people to know about them. I think of it as a push and pull: the external plot or that element of danger is pushing the story forward, but at the same time, the reader’s curiosity about the characters is pulling the story forward. I’m always reaching for that balance, but for me, a lot of it comes in revision. Once I’ve gotten the story down, I can think about the reveal of information.

Although the focus in this novel is on characterization, the novel is punctuated by scenes of extreme violence, which seemed necessary and compelling to me but might strike other readers as gratuitous. What did you think about the role of violence in the novel?

I think we have to measure violence based on what’s necessary for the story. I thought they were very jarring scenes, but they were fitting for these characters and the journey they were on. The title Descent brings so many elements of the novel together—on the one hand, you descend into the heart of each character, but you also descend into the heart of human nature and the horrible things that people are capable of. I don’t usually include a lot of violence on the page, but that’s because most of the stories I’m telling are taking place in the aftermath of an event. I’m more concerned with the emotional responses that characters have to the things that happened in their past, but that’s a personal choice.

I love what you said about the metaphor of descent. I’d mostly associated it with going down the mountain!

It didn’t really hit me until after I read, when I could see all these different elements coming together. I felt like gave it another whole level of meaning.

The climax of this novel depends on what could be described as coincidence. It’s a move I’d be afraid to make as a writer because of the way it tests the suspension of disbelief. What did you think about Johnston’s use of coincidence as a plot device?

I thought it really worked in this story. Coincidence happens a lot in life. Sometimes you’re the one who sees something, so you have the capability of altering the course of what follows. The idea for my last novel, The Only Survivors, began when a cell phone washed up at my feet on the beach. When I sent an early draft to my editor, I told her, “This is going to seem like a really big coincidence, but it’s actually the only true thing in the whole book!”

Setting plays a big role in this novel, and some reviewers have described it as a Western as well as a thriller. Sometimes I get tired of the old line about setting being a character, but it’s definitely hard to imagine this story taking place anywhere other than the Rockies. Do you have any thoughts on how Johnston uses setting? How do you choose settings for your work?

I love thinking about settings, both in my own work and as a reader. In this case, the tragedy at the heart of this novel happens when this family is on vacation in this totally picturesque, beautiful place. You can imagine them looking out the window and thinking, “Could you imagine a place more stunning? Look what the world is capable of.” And then after the daughter is abducted, it becomes, “How could I have brought my family to this horrifying, terrifying place where anything is possible?” Again, what is happening in the world—in this beautiful and awful place—is also happening inside the characters.

That’s so well-said. It just occurred to me that the novel begins in the summer, but then the final scenes take place in the winter. I’ve never been to the Rockies in the winter, but I imagine that it’s completely different place.

And that’s so often true. When you visit a place, you usually visit it in the tourist season, and it may be totally different at a different time of year. If you’re out in the woods, in the winter, there’s an element of survival that’s inherent in that story.

On Johnston’s website, it says he worked as a carpenter for many years. Grant Courtland is a contractor, and one thing I really enjoyed about the novel is the way characters spend a lot of time making, fixing, or doing things rather than just talking. How do you handle the problem of making scenes with a lot of dialogue compelling?

I love how he did that too. It gave another layer of texture and made these characters really come to life. I try to think about what the characters are doing, and if they’re at the beach and can be in kayaks or something, that’s great. Sometimes, though, they just have to be in the house or in a restaurant, and in that case, I try to think about dialogue more in terms of subtext. What is one character saying that the other character isn’t hearing? Sometimes it’s like two people having two totally different conversations.

Do you know Tim Johnston in real life? Have you read any of his other novels?

I was fortunate to find myself on a panel with him once at a book festival years ago. It was soon after I had read Descent, and it was so interesting to hear him talking about it. Since then, I’ve read The Current, which has a lot of similar elements. I’m not going to do this justice, but it’s about two young women whose car goes into a river in the winter, and one survives and one doesn’t, and there’s a mystery as well. And I think he also has a brand-new book that I’m looking forward to reading now that I’m through my edits.

Is there anything you’ve learned from this novel that you might apply to your own work?

It made me think about how to stay true to the story that you’re interested in exploring. As you were saying earlier, it doesn’t necessarily feel like a stereotypical thriller plot. After hitting those expected beats in the first chapter, it takes a lot of different avenues, and you’re exploring something different than you maybe thought you would be in the first chapter of the book. I have huge admiration for stories like that, and I feel like those are often the books I remember. Because they’re unexpected.