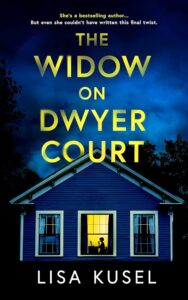

Some would say all writers are criminals. We steal bits of reality to make our fictional worlds. But is using someone else’s experience in your fiction really a crime? That’s the question I pondered as I wrote The Widow on Dwyer Court, a domestic thriller about an erotica writer who owes her popularity to her husband’s active and creative sex life—with women who aren’t her.

Thirty-six-year-old soccer mom Kate has never enjoyed sex, but she does love her handsome husband, Matt. They’ve struck a peculiar deal: Matt can indulge his appetites with strangers on business trips, as long as he tells all to Kate when he returns home. She, in turn, siphons Matt’s juicy tales into her fiction. Good story fodder is what gets Kate hot, and Matt is eager to oblige. But when he breaks one of the cardinal rules of their arrangement, somebody ends up losing the plot.

Mine is far from the only recent thriller in which writing goes hand in hand with criminal or at least questionable behavior, often involving rivalry with another writer or “theft” of a story. In Jean Hanff Korelitz’s The Plot, a frustrated writing teacher plagiarizes an idea from his deceased student and turns it into a bestseller. In R.L. Kuang’s Yellowface, a midlist author steals her more successful dead friend’s actual manuscript and publishes it as her own. In The Writing Retreat by Julia Bartz, two writer frenemies must write for their lives to compete for the grand prize of publication. In I’m Not Done With You Yet by Jesse Q. Sutanto, a midlist writer (yet again, frustrated!) stalks the college friend who surpassed her in every way.

Many of these novels are works of metafiction that feature excerpts from a book within the book that the protagonist is writing. This device is a brilliant way for the author to remind readers of the unreliability of all narratives and narrators, thus casting doubt on everything the protagonist tells us.

In The Widow on Dwyer Court, I include excerpts from Kate’s work-in-progress in the Strong Lust series, starring hunky hero Macon Strong. Kate lives in Vermont, and I use the novel-within-a-novel to have some fun with the state’s dairy-obsessed reputation. In one excerpt, for instance, Macon seduces his cheesemaking intern on a bucolic farm.

It’s easy to parody erotica, but I wanted my excerpts to be genuinely effective examples of the genre, as well. One satisfied reader tells Kate that the books have saved her marriage. The irony, then, is that Kate can write so well about something that she has no interest in doing in real life. Part of that is down to her stealing (or borrowing!) Matt’s experiences for material. But the skill with which she turns reality into fiction tells us that Kate has the writer’s gift of manipulating the details to spin a story her way.

If writers build whole worlds out of words, one negative review can be enough to bring those worlds crashing down. So, in thrillers about writers, the metafiction device is often paired with the theme of the author’s fragile, sensitive ego.

In Taylor Adams’ The Last Word, for instance, a woman suspects a horror author is stalking her after she leaves a one-star review. In R.F. Kuang’s Yellowface, the “author” of the stolen book becomes a bestseller but is punished by her own paranoia and social media obsession, hounded by fear of discovery at every turn.

In The Widow on Dwyer Court, Kate doesn’t have a writer rival. But her insecurity manifests in her fraught friendship with Annie, the titular widow, who just moved into the neighborhood. Annie is cool, fun, irreverent—and capable of actually enjoying the kind of adventurous sex that Kate can only write about. The novel opens with Kate having a blissful platonic threesome with Matt and the written word. But Annie disrupts that bliss, activating all Kate’s feelings of inadequacy and brewing up a recipe for trouble.

Can we trust everything Kate tells us? I won’t spoil the book by answering that question. But I can say that metafiction is a great tool for encouraging readers to question everything. And by keeping them off balance, we also keep them in suspense—the first task of every thriller writer.

***