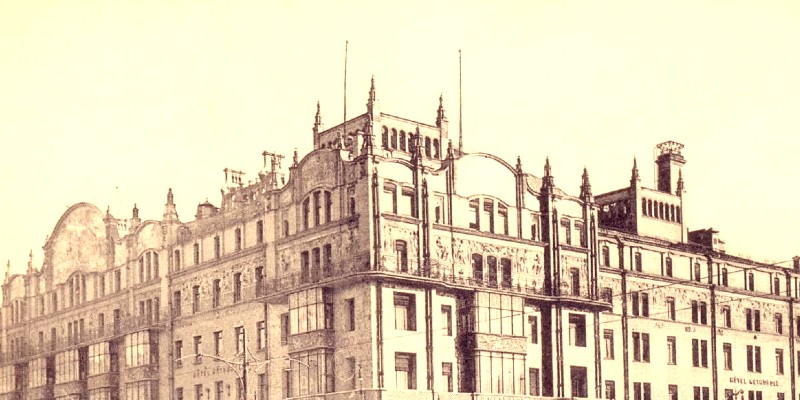

The most generous thing you could say about the Metropol Hotel in 1941 was that it had seen better days. When it opened in 1905, it stood as a shining example of the Art Nouveau style, combining the designs of avantgarde British and Russian architects with highly coloured elements of décor drawn from Russian folklore. At that time the capital of the Russian empire had for two centuries been St Petersburg on the Baltic coast, reducing Moscow to ‘a village with four hundred churches’. Despite this cruel label, Moscow at the start of the twentieth century was the home of Russia’s wealthy merchants, who at the time were leading art collectors, patrons of the country’s cultural elite and nurturers of progressive ideas. The Metropol was their showcase and their playground.

The year of its opening was a time of mass protests throughout Russia demanding reform from the autocratic Romanov dynasty. One of the first grand occasions held at the hotel was a dinner to celebrate the unpopular Tsar Nicholas II granting the Russian people the right to elect a parliament. Feodor Chaliapin, the great operatic bass who was the son of a peasant, marked the occasion by climbing up onto a table under the vaulted glass ceiling of the dining room – the space was originally designed as a theatre, hence its huge dimensions – and singing unaccompanied the revolutionary anthem, the ‘Song of the Volga Boatmen’. He then passed a hat around the diners to collect donations to support the strikers.

As Russia recovered from the upheaval of 1905, the hotel proved an instant hit for those with money to spend. Sugar barons flaunted their wealth with rivers of French champagne, and cavalry officers invited ballerinas from the nearby Bolshoi Theatre to join them for a post-performance supper. Tsarist gallants invited their guests up to one of the private rooms on the first-floor balcony where they could look down on the diners below or close the curtains for an intimate soirée.

The British diplomat and spy Robert Bruce Lockhart captured the dissolute atmosphere of the hotel when he first visited in January 1912 and, having put off the call girls who pestered him by phone, went down to the restaurant. ‘My first impressions were of steaming furs, fat women and big sleek men; of attractive servility in the underlings and of good-natured ostentation on the part of the clients; of great wealth and rude coarseness, and yet a coarseness sufficiently exotic to dispel revulsion. I had entered a kingdom where money was the only God.’

Unsurprisingly, the hotel acquired a reputation as a place where bourgeois mothers did not want their daughters to be seen – the phrase ‘girls of the Metropol’ would be used with a knowing wink for decades to come. Bruce Lockhart describes gaily lit windows on the first floor with doors opening into the cabinets privés where, hidden from prying eyes, ‘dissolute youth and debauched old are trafficked for roubles and champagne for songs and love’. The restaurant was a maze of small tables, crowded with officers in badly cut uniforms, Russian merchants with scented beards, and German commercial travellers with sallow complexions. At the end of the dining room was a dais where a red-coated orchestra played, led by a Czech violinist who performed from a little pulpit. Sometimes the orchestra crashed out a waltz loud enough to drown the popping of corks and clatter of plates. At other times, the violinist turned round to face the diners and brought tears to their eyes with his doleful gypsy tunes.

When the Bolshevik Revolution overthrew the provisional government that had replaced the Romanov dynasty in November 1917, Tsarist officer cadets chose the Metropol to make their last stand in Moscow against the victorious Reds. They were forced to surrender when the revolutionaries brought up field guns to bombard the hotel; the damage was still visible on the walls in the 1940s. Bruce Lockhart was uniquely well placed to chart the hotel’s abrupt transition from playground of the rich to a bastion of the Bolsheviks. When he returned, after the Bolsheviks had seized power, he was the guest of Leon Trotsky, firebrand of the Revolution. Trotsky was haranguing members of the new Bolshevik government from the same dais where the Czech violinist had until recently entertained the cream of Moscow society.

In that year the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin had moved the capital back to Moscow from St Petersburg – an imperial city too closely associated with the Tsars to suit the workers’ state – and he requisitioned the hotel as a dormitory and offices for the new rulers. The hotel was renamed the Second House of Soviets and became the home and workplace of senior Bolsheviks. It was from here that the fateful telegram was sent ordering the Reds to massacre Tsar Nicholas, the Tsarina Alexandra and their five children in Ekaterinburg in 1918. Lenin and Stalin both addressed grand occasions in the hotel’s dining room.

The new communist rulers paid no heed to the upkeep of such a bourgeois icon, and standards fell rapidly. The depths to which the hotel had sunk after the Revolution are described in a 1920 account by a Russian official. While blood was being shed in the civil war, the Metropol was filled with people getting drunk on vodka, champagne, and wines from the Caucasus. ‘Dirt and cigarette butts were everywhere . . . residents chopped firewood and used primus stoves in their rooms, clogged the sinks and toilets with garbage, lay on the beds with their boots on, carried food and hot water up and down the stairs, hung up their wet clothes in the halls, brought in unauthorized guests, claimed to be someone they were not and often behaved in a rude and downright outrageous manner.’

Clare Sheridan, a British sculptor who visited Moscow in the early 1920s, wrote in her diary of life in the Metropol: ‘The drain smells are such that one climbs the stairs two at a time holding one’s breath! There are bits of the Kremlin that are enough to kill the healthiest person, but the Metropole [sic] baffles all description. Inside the offices it is all right, but the double windows everywhere are hermetically sealed for the winter, and I wonder that people do not die like flies.’ Arthur Ransome, who reported from Moscow in the 1920s and later became the author of the children’s book Swallows and Amazons, described how people lived in the absence of room service. ‘And all the time people from all parts of the hotel were coming [to the kitchens] with their pitchers and pans, from fine copper kettles to disreputable empty meat tins, to fetch hot water for tea.’

By the 1920s the sleek and fur-clad clientele the hotel was built for had either fled abroad and were working as taxi drivers in Paris or Shanghai, or were lying low as ‘former people’ whose wealth, property and even clothes were requestioned by the Revolution. In their place came commissars in leather jerkins demanding accommodation, peasants from far-flung provinces bringing written notes of the progress of the civil war or the spread of famine, and all manner of desperate people begging for a square meal from the Metropol’s dining room, now a cafeteria.

The Revolution had set out to destroy ‘bourgeois morality’, leading to an outburst of sexual liberation, prompted by the reputed comment of the revolutionary theorist Alexandra Kollontai that ‘the satisfaction of sexual desires, of love, will be as simple and unimportant as drinking a glass of water’. The revolutionary ‘glass of water theory’ of sexual relations after women were liberated from the bourgeois norms of marriage was hotly debated in Russia in the 1920s – and denounced by Lenin. Alexandra Kollontai did indeed describe sex in terms of a human need like water, but the origin of the sentence which is often attributed to her remains unclear. The hotel manager appointed by the Bolsheviks tried to stop the Metropol becoming a brothel. When he stopped ‘non-party women’ coming to visit a senior member of the Cheka, the new secret police, the latter told him: ‘You are not my father, priest or protector.’ In the manager’s eyes, Moscow had become a ‘bubbling, rumbling, rotting and gurgling swamp’.

Some semblance of order was restored in the mid-1920s when the government found a new use for the hotel. Having recovered its pre-revolutionary name, it was designated as the place to accommodate influential visitors from the West. The face of Soviet hospitality looked very much like the Tsarist version, minus the fine crockery that had been pilfered in the years of chaos. With the Bolsheviks believing that worker-led revolution was fated to take over the world – and that Soviet power was not safe in Russia until that happened – a new industry arose to market the Soviet Union abroad. In 1925 the All-Union Society for Relations with Foreign Countries, known as VOKS, was set up to ensure that visitors received a positive impression of the emerging Soviet state. Guides and interpreters were put through a 160-hour training course to ensure that influential visitors – ‘useful idiots’ in Lenin’s term – went home with an impression of peace, progress and bountiful supplies of everything, even when famine was stalking the land. A VOKS guide, according to Ekaterina Egorova, historian of the Metropol, was not a hired servant, as in the West, but a companion who was ‘a comrade with a rigorous political foundation’. Guides should present Soviet achievements ‘in the appropriate context and scale’. They were required to inform on the visitors they were showing around: who they met, what interested them and what questions they asked. Stock answers to tricky questions were supplied as part of the training course, such as ‘Are infectious diseases widespread in the USSR?’ Answer: ‘Since the application of our social legislation, infectious diseases have ceased.’

Or this one: ‘Do convicted bribe-takers enjoy the right of early release from their sentences?’ Answer: ‘No, like all members of the intelligentsia who have not emerged from the ranks of the proletariat, they do not enjoy this right.’

These bone-headed responses might suggest that the charm offensive was cack-handed and ineffectual. While the guides reported that some visitors were inveterate anti-communists and Russophobes, this propaganda barrage worked on a stream of progressive academics, liberal clergymen and others who clung to the Soviet experiment as a way out of the poverty and unemployment that gripped the capitalist world following the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

Most famously, George Bernard Shaw, the Irish playwright, avowed communist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, visited Moscow in 1931 to celebrate his seventy-fifth birthday. The Russians honoured him with banquets at a time when food was in short supply. In the absence of his wife, who was ill, Shaw was accompanied by Nancy Astor, a Conservative MP and the first woman to take a seat in the House of Commons. Despite their clashing political views, they admired each other and had a lifelong friendship. While in Moscow, Lady Astor provided a muted counterpoint – she liked to denounce communists as thieves – to Shaw’s fulsome praise of the Soviet system. No flattery was spared for Shaw: on a visit to the theatre, the whole cast unrolled a huge banner in praise of the writer. Stalin accorded the Shaw/Astor double act a two-hour meeting, unprecedented for a visiting literary figure. The smooth progress of the charm offensive stuttered briefly when the Metropol lift broke down between floors with Shaw and Lady Astor in it and they had to be pulled out.

On return to Britain, Shaw’s impressions dominated the headlines. Ever the provocateur, he said he had never eaten better than in Russia. Within a year, the quickening pace of Stalin’s collectivisation of agriculture had unleashed famine on Ukraine. Shaw did not speak of the prison camps that Stalin was filling with real or imagined enemies, though Lady Astor had had the courage to confront Stalin and ask him why he was killing so many Russians. There is some doubt that Stalin’s interpreter dared to translate the question correctly.

In 1935, the British Fabian socialists, Sydney and Beatrice Webb, stayed in the Metropol and then published their two-volume panegyric to Stalin’s Russia, Soviet Communism: A New Civilisation? For later editions, published in wartime after the USSR joined the Allies, they removed the question mark.

As the 1930s drew to a close, Stalin unleashed a two-year reign of terror known as the Great Purge, which saw residents of the Metropol regularly dragged from their beds. One of the many thousands of Stalin’s victims was Evgeny Veger, a rising star of the Communist Party, who lived in two rooms on the second floor of the hotel with his pianist wife Solange and their children. On the night of 25 June 1937, the tramp of boots was heard in the corridor, then a woman wailing and a male voice trying to comfort her. After that, silence. The next morning, one of the rooms occupied by the Vegers was closed with a leaden seal. The sound of weeping drifted down the corridor from the Boyarsky Zal, a function room where Solange had sought refuge to hide her distress from the children. Veger was executed five months after his arrest. Solange did not suffer the usual fate of wives of victims of the Terror– a spell of forced labour in a camp for ‘families of traitors to the motherland’ – and was placed in a psychiatric hospital instead.

After Stalin’s death in 1953 the political elite were no longer at risk of arrest in the middle of the night, and the Metropol settled into a more comfortable role, as the best of a bad bunch of Moscow hotels with a restaurant serving poor food where no one could get a table. In the 1960s the visiting Labour politician Tom Driberg, openly homosexual at a time when homosexuality was illegal in Britain, discovered behind the Metropol a 24-hour urinal which appeared to be the only gay pick-up place in Moscow. On Driberg’s recommendation, Guy Burgess, the Soviet spy who had fled Britain to live in Moscow, went there and found a companion in a young electrician called Tolya.

After the long era of stagnation under Brezhnev, the death of Communist Party rule was marked by a celebratory dinner at the Metropol in 1991. The exiled cellist Mstislav Rostropovich had returned to Moscow to support demonstrators resisting the hard-line Communist putsch against Mikhail Gorbachev; his concert outside the White House, the bastion of the anti-putschists, was one of the defining moments of the resistance. Afterwards, he and his wife, the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, celebrated the defeat of the putschists at a dinner in the Metropol – the place where more than thirty years earlier they had first met and fallen in love, before leaving Russia in the 1970s.

In 1993, when Michael Jackson stayed at the hotel, there was a faint echo of Chaliapin’s performance almost ninety years before, albeit against a less heroic backdrop. The pop star had climbed onto the stage at one end of the dining room to examine the harp that is played each morning during breakfast. He plucked a string and – such was the hotel’s hold on the collective imagination – launched a rumour that he had given an impromptu performance under the glass dome. The Metropol has been owned since 2012 by Alexander Klyachin, a Russian businessman and owner of an international hotel chain, who has modernised it, while preserving the unique features of a significant cultural monument.

___________________________________